16. THE GREAT DEPRESSION

AN ECONOMIC DEPRESSION HITS AMERICA HARD

CONTENTS

Hoover's indecision Hoover's indecision

The spiral downward of the American The spiral downward of the American

economy

America and the world during the America and the world during the

Hoover Administration

The Bonus Army incident The Bonus Army incident

The 1932 presidential election The 1932 presidential election

Roosevelt: The story behind the man Roosevelt: The story behind the man

The Depression has deepened as The Depression has deepened as

Roosevelt enters the White House

Roosevelt quickly sets out to institute a Roosevelt quickly sets out to institute a

"New Deal" for America

The Supreme Court shoots down FDR's The Supreme Court shoots down FDR's

New Deal programs

Persistent drought creates the Midwest Persistent drought creates the Midwest

"Dust Bowl"

Migration West to California takes up in Migration West to California takes up in

earnest

Poverty remains a serious problem Poverty remains a serious problem

throughout the 1930s

"Roosevelt's New Deal brought us out of "Roosevelt's New Deal brought us out of

the Depression" ... yes or no?

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 507-522.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1930s |

The Great Depression

1930 Initially, Hoover takes no action to counter the Depression ... seeing the crisis as purely economic ... not political

1932 At this point almost 30% of the American workforce is unemployed

Hoover sponsors the Emergency Relief and Construction Act to employ

workers ... getting criticism from the Democrats for attempting to introduce "Socialism"

Hoover worsens

his cause dramatically by refusing to cooperate with a "Bonus Army" of

17,000 unemployed

former soldiers ... who converge on DC (May) to request that a promised

pension be given them now

(rather than 10 years later); Hoover eventually (Jul) sends

troops to clear out their DC encampment

The Democrats

succeed in getting the voting public to see Hoover as the cause of the

Depression ... and Roosevelt (Teddy's nephew Franklin) campaigns promising an (unspecified) "New Deal" – gaining a huge victory in the presidential elections (Nov)

1933 Roosevelt's New Deal actually turns into exactly the Socialism that the Democrats had accused Hoover of attempting ... except that the New Deal involved an extensive takeover of the nation's economy

by the Roosevelt government; the whole

thing is justified by pointing out the dangers and

evil of a greatly failed "Capitalism" (privately owned industry)

Roosevelt's New Deal develops public parks, builds hydroelectric dams,

highways, and municipal buildings), controls agricultural prices, regulates the banking and

investment industry, and creates the

Social Security retirement trust fund ... helping put many of the

unemployed back to work ... and helping to stablize the economy

1935 At this point, the Supreme Court begins to declare Roosevelt's New Deal

programs as unconstitutional ... upsetting Roosevelt greatly

A massive and

lasting drought hits the American mid-West ... creating the "Dust Bowl"

(1935-1937) ... forcing farmers to abandon their farms and head West – looking for work of any kind

1936 Roosevelt is reelected with a 61% popular majority and near total sweep of the electoral vote (Nov)

1937 So annoyed is Roosevelt with the Supreme Court that he announces plans to expand the number of Court justices (with his own appointees) ... but

backs down when even Congressional Democrats refuse to go along with the plan; this

plan also damages his popular support

Then, with all of the New Deal work projects now completed,

unemployment climbs back up again (private industry had not made any kind of

comeback during the New Deal era) ... and America slides back into the Depression

Auto and steel worker strikes grow violent in confrontations between striking workers, scabs, and police or security-service personnel ... with

numerous brutal deaths often accompanying these conflicts; 18 people die in a battle between

strikers and scabs at Republic Steel's plant ... and police kill ten and wound many more strikers and family members simply gathered for a Memorial

Day picnic near Republic Steel's plant in Chicago (both events in late

May)

Blacks also receive the wrath of frustrated (and crazily angry) Whites

The idea of massive trans-Atlantic flight via huge blimps collapses

with the tragic destruction of the massive blimp Hindenburg (May)

|

|

The October 1929 crash occurred during the first

year of the presidency of the Republican Herbert Hoover, the famous

philanthropist who at the end of the Great War had organized a huge

relief effort for the starving people of war-torn Belgium. Now it was

his turn to do something about a worsening economic picture in America.

In the face of this massive shock to the

American stock market, Hoover tended to follow the common wisdom of the

Republican Party (which had long dominated American politics) which was

simply to follow the central principle of capitalism and let the market

correct itself; it was not the government's job to meddle with the nation's economy.

|

A very wearied President

Hoover at a gridiron dinner – March 1932

A very wearied President

Hoover at a gridiron dinner – March 1932

|

Hoover looked especially to his Secretary of the

Treasury Mellon for encouragement and advice. But Mellon's approach to

the depression was not only Republican but even rather Darwinian:

government should not intervene, but instead allow a natural

liquidation or shake out of weak or poor business factors (notably

labor, farmers, and small businesses) in the market mechanism. But

ultimately this philosophy helped no one, not even the big capitalists

who depended on an affluent society to sell their products to. Enforced

poverty helped no one. The economy worsened. Eventually Mellon was

dismissed by Hoover – though only when his failure to pay federal income taxes was discovered. |

Hoover's

Treasury Secretary,

Andrew Mellon

THE SPIRAL DOWNWARD OF THE AMERICAN ECONOMY |

Some of the 6,000 men who

queued up for jobs offered by a New York employment agency – 1930

(135 found jobs; by 1932

almost 30% of the American workforce was unemployed)

Some of the 6,000 men who

queued up for jobs offered by a New York employment agency – 1930

(135 found jobs; by 1932

almost 30% of the American workforce was unemployed)

A Brooklyn family evicted

from their apartment

A Brooklyn family evicted

from their apartment

Shacks of the Seattle's

"Hooverville"

Shacks of the Seattle's

"Hooverville" A typical "Hooverville" shack

built during the Depression around cities with high

unemployment. As

1930 turned

into 1931, and 1931 into 1932, the economy only worsened

A typical "Hooverville" shack

built during the Depression around cities with high

unemployment. As

1930 turned

into 1931, and 1931 into 1932, the economy only worsened

|

Belated government efforts to support the economy

Finally and belatedly, as the economy continued

to fail to revive (one fourth of American workers were unemployed),

Hoover began to propose government measures to try to help out the

worst parts of the economy. The 1932 Emergency Relief and Construction

Act attempted to start up public works programs to put the unemployed

to work and to provide government-secured capital to help start up

industries. But these measures came too late to swing the country back

in support of Hoover's presidency. Besides, the Democrats smelled

political victory in the November 1932 elections and were not in a mood

to be very cooperative with the Hoover presidency, which they were

pleased to blame as the cause of the Depression.

|

AMERICA AND THE WORLD DURING THE HOOVER ADMINISTRATION |

|

Congress

at one point attempted to help the economy – through the erecting of a

new trade barrier (the infamous Hawley Smoot Tariff) designed to

protect struggling American producers. But it only made the situation

far worse. It stirred up a trade war with America's trade partners –

who in retaliation against American protectionism moved to protect

their own industries from American competition. Ultimately this merely

helped to pass the depression on to the rest of the Western world.

|

Otherwise, America's foreign policy was one

basically

of isolationism – except within its own Western Hemisphere where it continues its

economic

overlordship

Henry Stimson, Hoover's

Secretary

of State – 1931 (he eventually became a

believer in non-intervention in Latin American affairs)

Henry Stimson, Hoover's

Secretary

of State – 1931 (he eventually became a

believer in non-intervention in Latin American affairs)

One of the biggest issues

of the times was the anti-capitalist / anti-American uprising in Nicaragua led

by the charismatic Augusto Sandino

| Over a period of

six

years he attacked

American military forces in his country – until their removal in 1933.

He then retreated from public view – but was murdered the following year

under the orders of the commander of the National Guard, Anastasio Somoza – who soon maneuvered himself into position as Nicaraguan

dictator. |

Nicaraguan rebel leader Augusto

Sandino – [right] enroute to Mexico. June 1929

Nicaraguan rebel leader Augusto

Sandino – [right] enroute to Mexico. June 1929

National Archives

NA-127-N-522050

"One of our speed cars mounted

with Heavy Browning Machine Guns to offset any possibility

of rioting during the 1932 Presidential Elections in Nicaragua." photo by

Capt Charles Davis.

"One of our speed cars mounted

with Heavy Browning Machine Guns to offset any possibility

of rioting during the 1932 Presidential Elections in Nicaragua." photo by

Capt Charles Davis.

National Archives

Sandino's Flag – Nicaragua

- 1932

Sandino's Flag – Nicaragua

- 1932

THE BONUS ARMY INCIDENT (1932) |

|

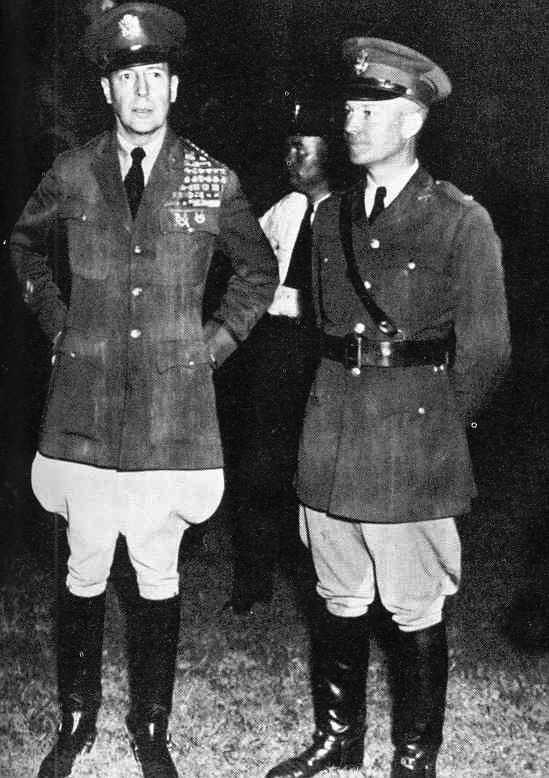

One sad incident that happened toward the end of

Hoover's presidency was the march on Washington of the Bonus Army in

the summer of 1932. The marchers came to Washington, D.C., to demand

their veterans' bonus payments early from Congress, a bonus that had

been promised them for their service in the Great War. But the payments

were not due to begin until 1945. The veterans wanted them now – even

if it meant they would be receiving these bonuses at a lower rate. They

and their families needed the money now in order to survive. After

several months of camping near the Anacostia River, and after several

confrontations with police, federal troops (commanded by Douglas

MacArthur and his staff assistant Dwight D. Eisenhower, aided by George

Patton), upon orders by Hoover, drove the marchers from the city. The

roughness of the police and troops on these war veterans shocked the

nation – and further alienated the people from the Hoover

administration.

|

Some of the 17,000 members

of the "Bonus Army" who had descended on Washington,

D.C. in mid 1932 vowing not to leave until

the bonus promised them for service during the War was paid.

Some of the 17,000 members

of the "Bonus Army" who had descended on Washington,

D.C. in mid 1932 vowing not to leave until

the bonus promised them for service during the War was paid. "Bonus Army" encampment in

Washington, D.C. – 1932..

"Bonus Army" encampment in

Washington, D.C. – 1932..

"Bonus Marchers" and

police

battle in Washington, DC.

"Bonus Marchers" and

police

battle in Washington, DC.

National Archives

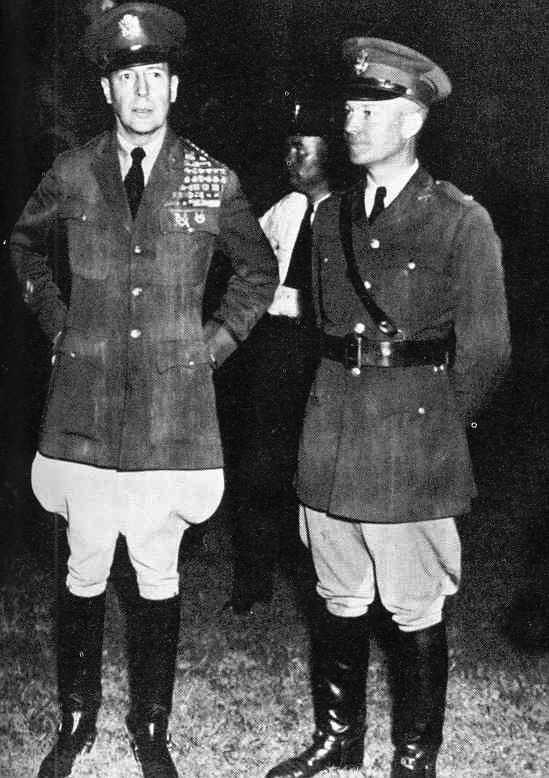

General Douglas MacArthur

conferring with his aide, Major Dwight D. Eisenhower about plans for evicting

the Bonus Army from Washington, D.C. – 1932

General Douglas MacArthur

conferring with his aide, Major Dwight D. Eisenhower about plans for evicting

the Bonus Army from Washington, D.C. – 1932

General MacArthur and Major

Dwight Eisenhower in uniform

General MacArthur and Major

Dwight Eisenhower in uniform

prior to the forceable dispersing

of the Bonus Army – 1932

Federal troops tear-gassing

the Bonus Army – July 1932

Federal troops tear-gassing

the Bonus Army – July 1932

THE 1932 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION |

|

General disillusionment with the Republican Old Guard

politicians paved the way for Franklin D. Roosevelt to gain a grand victory in the 1932

elections

Hoover was an easy target for his opponent, Franklin D. Roosevelt, in

the 1932 presidential race. Roosevelt took Hoover to task for his many

failures as president in dealing with this national crisis. Ironically

one of his favorite lines of attack during the campaign was Hoover's

extravagant spending in order to buy the country out of the economic

crisis – and how Hoover wanted to turn Washington into the control

center of the American economy. Roosevelt's Vice-presidential running

mate, Nance Garner, even accused Hoover of advancing the cause of

Socialism in America. How ironic, for the incoming Roosevelt

Administration would not only undertake exactly these same kind of

Washington-directed measures – but would do so in massive proportion!

Blaming

Capitalism for the Depression

No one really understood the actual

dynamic that had caused the Depression: the fanciful belief that

reached down to very ordinary Americans that somehow the fast path to

wealth offered through Wall Street investment was destined to go on

forever and the presumption that the hot consumer market that kept

millions employed was also a permanent feature of American life. The

1920s economy was all so new that there was bound to be little

perspective available to the average American as to how economics

actually worked. And when the dream came crashing down, confusion, then

bitterness, naturally took over. Worse, Americans grasped ahold of easy

explanations, simple portrayals of evil behind this whole catastrophe.

And history reveals that there is nothing uglier to behold than a

society's treatment of a respected prophet, whose prophecies have

failed to come to pass. And in the case of early 1930s America those

failed prophets would be the capitalists, once worshiped as gods, and

now despised as the very devils themselves.

And Roosevelt picked up on this opportunity to use exactly just that

imagery in this run against the heavily pro-capitalist Republican

Party. Using Christian religious imagery quite familiar to the American

people, in his acceptance speech as the Democratic Party's presidential

candidate he blamed the depression on those among the American people

who had "made obeisance to Mammon" (worshiped wealth and the providers

of just such wealth). This attack on the prophets of capitalism played

well, for to the average American it was the only thing that made sense

as they faced a surrounding world of economic disaster. The capitalists

themselves had caused this through their own greediness. What Americans

now needed was a nation run by compassion, directed not by capitalism

but by a government in Washington sensitive to the needs of the people.

And Roosevelt promised to be exactly that sensitive caretaker if

elected. During his campaign he regularly employed Christian ideals and

language that had been at the heart of the older Social Gospel,

promising the people in so many words that the Democratic party would

do the "Christian thing," unlike the insensitive pro-capitalist

Republicans. And of course the tactic worked beautifully, because the

Republicans had no countering ideas to offer. Clearly the god

Capitalism had failed.

The November elections were extremely sad for Hoover and elating for

Roosevelt. Roosevelt had received 57.4 percent of the popular vote to

only 39.7 percent for Hoover. And the electoral vote went 472 for

Roosevelt and 52 for Hoover.

And just to drive home this anti-capitalist message, in his

inauguration address delivered in early 1933, he not only issued his

famous "firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is, fear

itself" he went on to attack the legacy that greedy capitalism had left

Americans with. Again, using familiar Christian terminology to bash the

greedy agents of capitalism, whom he referred to as "the money

changers," he stated:

...rulers of the exchange of

mankind's goods have failed through their own stubbornness and their

own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and have abdicated.

Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the

court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men.

The money changers have

fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may

now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the

restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more

noble than mere monetary profit.

His promise to the American people was that his administration would

now take over the matter, and undertake action, such as capitalism had

failed to do in the face of this national tragedy.

I am prepared under my

constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken Nation in

the midst of a stricken world may require. These measures, or such

other measures as the Congress may build out of its experience and

wisdom, I shall seek, within my constitutional authority, to bring to

speedy adoption.

And thus it was that Americans now hungrily looked to Washington – not

Wall Street – to move their lives forward. None dared call this

Socialism (except a group of Humanists that year who were proud to do

so) because in a still highly individualistic America, Socialism

remained largely a taboo concept. Thus the Roosevelt program was never

assigned any other label except "New Deal," although Roosevelt's

actions would come to look amazingly like that which was going on in a

number of European countries faced with the same problem. Many

Americans were quick to point this out. But it was not wise to speak

out too much about what was happening to an American society

increasingly dependent on the good intentions of political authorities

gathered in Washington. The election had made it quite clear: the

majority of the Americans had just given Roosevelt full authorization

to fix the problem any way he saw fit to do so.

It is important to note however that behind this

carefully chosen anti-capitalist political stance there existed a very

strong personal faith that moved Roosevelt, one which actually guided

him very strongly as he made his way through the challenges before him.

He had been raised a believing Episcopalian and had been directed in

key times of his life by strong Christian counsel, and called on that

faith when he was stricken in the prime of his professional life by

crippling polio. But he was an overcomer by character, amazingly

confident that all challenges could be met simply by seeking to do the

right thing. He believed strongly in a God of justice and fairness, and

a sense that despite – or even because of – his crippling affliction he

had been chosen by God to show the world how to overcome life's worst

challenges. He was therefore incredibly optimistic, a personal trait

that would attract many to this man of enormous moral and spiritual

strength, including a nation that would somehow have to keep moving

forward even in the darkest of times. That was his understanding of his

Christian faith, a matter of enormous importance to him, and as he saw

it, to America and the world as well. |

FDR stumping along the Jersey

shore – 1932

FDR stumping along the Jersey

shore – 1932

Roosevelt meets

farmers

Roosevelt meets

farmers

FDR whistle-stopping in

Goodland,

Kansas – 1932. He promised a "New Deal"

- and the repeal of the 18th Amendment on Prohibition

FDR whistle-stopping in

Goodland,

Kansas – 1932. He promised a "New Deal"

- and the repeal of the 18th Amendment on Prohibition

Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers

a speech in New Albany (Indiana) during the 1932 Presidential

campaign

Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers

a speech in New Albany (Indiana) during the 1932 Presidential

campaign

1932 Democratic Presidential

nominee Franklin Delano Roosevelt and VP nominee John Nance

Garner

1932 Democratic Presidential

nominee Franklin Delano Roosevelt and VP nominee John Nance

Garner

FDR, with his son James,

being introduced by the comedian Will Rogers – 1932

FDR, with his son James,

being introduced by the comedian Will Rogers – 1932 The presidential election

of 1932

The presidential election

of 1932

Hoover and Roosevelt on the

latter's inauguration day – 1933

Hoover and Roosevelt on the

latter's inauguration day – 1933

Franklin Roosevelt delivers

his inaugural address, March 4, 1933

Franklin Roosevelt delivers

his inaugural address, March 4, 1933

Franklin Delano Roosevelt,

1933

Franklin Delano Roosevelt,

1933

ROOSEVELT: THE STORY BEHIND THE MAN |

The making of the president

Roosevelt was born in 1882 in the Hudson

River Valley town of Hyde Park to a very prominent New York family, was

raised as an only child in considerable privilege, and was watched over

carefully by a doting mother, Sara. Sara, who was of Massachusetts

stock, directed him to spend his summers in her home state (when not in

Europe, which the family also visited every year) and had him enrolled

in the prestigious Groton Academy in northern Massachusetts. Most

significantly, here under the direction of the Episcopal priest and

school headmaster Endicott Peabody,1

he was taught the importance of those raised to privilege in developing

a commitment to public service – but also the importance of a strong

Christian sense of responsibility toward those less fortunate than

they. This effort of Peabody's would not be lost on Roosevelt.

As was generally expected of a Groton

boy, he then went on to study at Harvard, where he continued his

standing as an average student. But while at Harvard he began to

develop political ambitions, particularly with his uncle Theodore

(Teddy Roosevelt) becoming U.S. president at that time. He now had a

political role model to follow – however as a Democrat, unlike his

Republican uncle (nearly all those around him, even since he had

entered Groton, were also Republicans).

With the death of his father James at the

end of 1900, Roosevelt's mother Sara became even more directly engaged

in her son's life (she had even followed him to Boston when he was at

Harvard). But Franklin finally found that a relationship which

developed in 1902 with Eleanor Roosevelt (Teddy's niece and thus a

distant cousin of Franklin's) allowed him to free himself considerably

from his mother's domineering ways (Sara was very opposed to Franklin's

and Eleanor's relationship).

The next year he graduated from Harvard and entered Columbia Law School

in New York City, and a year and a half later (March 1905) married

Eleanor. Then soon, having passed the New York State Bar exam, he could

see no reason for continuing his law studies and dropped out of

Columbia in 1907. The next year he took a job with a New York City Wall

Street firm, where he specialized in corporate law.

His marriage with Eleanor was not an easy

one for either of the two. They had six children in fairly short order

between 1906 and 1916, although the third child died soon after birth.

They both took the child's death very hard. Also in moving after their

marriage to the Roosevelt estate (Springwood), Sara moved in with them,

a constant source of irritation for Eleanor.

Also, Franklin had a fascination with a

number of other women, producing scandals – especially his affair with

Eleanor's social secretary, Lucy Mercer. Divorce was considered – but

Lucy was not interested in a marriage with Franklin (too many

complications). His marriage with Eleanor thus somehow survived, after

he promised not ever to see Lucy again (a promise he did not keep). But

it was a cold marriage, mostly thereafter just an arrangement of some

small degree of social and political convenience. Eleanor found herself

busied elsewhere with a number of social causes that kept her away from

her husband.

In 1910 Roosevelt ran for the position as

New York State senator, the local Democrat Party glad to have a

Roosevelt name to put forward in a district that had been solidly

Republican since before the Civil War, and shocked when he was actually

elected to the position. In the New York Senate he found himself in

opposition to the New York Tammany Hall political machine, and

consequently developed considerable experience in the art of political

maneuvering – which helped him be reelected to the Senate position in

1912 as something of a distinct social reformer or progressivist. But

that same year he had also thrown personal support to the reformist

Democratic Party presidential candidate, Woodrow Wilson (who also was

running against Franklin's uncle), earning Franklin a cabinet

appointment as the assistant secretary of the navy – a position he

would hold for the next seven years, (ironically, the same position

that also his uncle had held in the early years of his national

political career). Also, like his uncle, the younger Roosevelt actually

had long been interested in naval affairs, was very well read-up on the

subject, and was fully capable of being an excellent contributor to

American naval policy. He would continue to serve in this capacity

through the years of the Great War.

In 1920, the Democratic National

Convention picked Roosevelt, only thirty-eight at the time, to run as

the party's vice-presidential candidate, serving alongside the party's

presidential candidate, Ohio Governor James Cox. But the election

turned into a landslide for the Republican ticket of Warren G. Harding

and Calvin Coolidge. After the election Roosevelt returned to his law

practice in New York.

But tragedy struck in August of the next

year (1921). He contracted polio while vacationing at Campobello Island

in Canada, the polio leaving him permanently paralyzed from the waist

down. A man of iron will, he refused to admit defeat by the disease and

maintained his law practice, while at the same time attempting various

therapies. In 1926 he purchased a resort at Warm Spring, Georgia, not

only for his own treatment, but for others also afflicted with the

disease. His disease in fact had become for him something of a cause,

and two years later he created the organization that would eventually

become the famous March of Dimes, dedicated to fighting the scourge of

polio. He also developed immense upper body strength and the ability to

walk (short distances) with the aid of iron braces, often also leaning

on the arms of an assistant – so as not to have to appear in public in

a wheelchair.

In the meantime, he kept up with New York

Democratic Party politics, improving his relations with Tammany Hall,

and supporting Alfred E. Smith in the New York race for governor in

1922 and again in 1924 (which Smith won), then for U.S. president in

1928 (which Smith lost). At the same time Smith encouraged and

supported Roosevelt's candidacy for New York governor in 1928, which

Roosevelt won (twice) making him the state's governor from 1929 to

1932, when he chose to run for the U.S. presidency.

And in 1932, with the country caught in

the depths of the Great Depression his win over his Republican opponent

Hoover (naturally blamed for the tragedy) was fairly easy: Roosevelt

was elected to the U.S. presidency with one of America's widest margins

of victory (14 percent) over his Republican opponent.

1Roosevelt became very close to Peabody, having him preside at his wedding with Eleanor and at the weddings of his children.

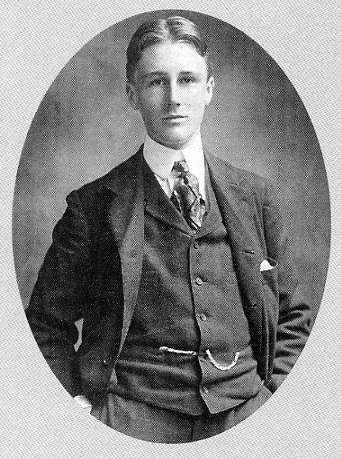

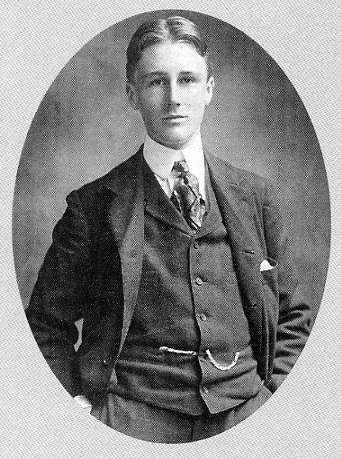

A young FDR and his mother

Sara

A young FDR and his mother

Sara

FDR as a last-year student

at Groton at age 18

FDR as a last-year student

at Groton at age 18

Eleanor Roosevelt in

Venice

Eleanor Roosevelt in

Venice

Asst. Secretary of the Navy

Roosevelt exhorting the crowd to buy Victory Loan bonds – 1919

Asst. Secretary of the Navy

Roosevelt exhorting the crowd to buy Victory Loan bonds – 1919

Democrat Vice-Presidential candidate FDR< with Presidential candidate

3-term Ohio Governor James Cox – 1920

Democrat Vice-Presidential candidate FDR< with Presidential candidate

3-term Ohio Governor James Cox – 1920

Polio-stricken FDR being

helped from a car (he contracted the debilitating

disease in 1921 at age 39 – but generally hid it from public view)

Polio-stricken FDR being

helped from a car (he contracted the debilitating

disease in 1921 at age 39 – but generally hid it from public view)

THE DEPRESSION HAS DEEPENED CONSIDERABLY AS ROOSEVELT ENTERS THE WHITE HOUSE |

Selling apples

Selling apples

Distributing apples for the

unemployed to sell on street corners

Distributing apples for the

unemployed to sell on street corners Land auction – Spotsylvania,

Virginia -

1933

Land auction – Spotsylvania,

Virginia -

1933

Unemployed Americans lining

up for relief assistance

Unemployed Americans lining

up for relief assistance

Soup and Bread

Line

"White Angel

Breadline"

"White Angel

Breadline"

Relief in a soup

kitchen

Relief in a soup

kitchen

Bread and canned goods being

distributed by St. Peter's Mission in New York City

Bread and canned goods being

distributed by St. Peter's Mission in New York City

Some economic life does move

forward in America during the 1930s despite the tough times

"Old-timer, keeping up with

the boys. Many structural workers are above middle-age. Empire State [Building]"

"Old-timer, keeping up with

the boys. Many structural workers are above middle-age. Empire State [Building]"

Construction work on the

1250 foot high Empire State Building

Construction work on the

1250 foot high Empire State Building

|

The basic philosophy of the "New Deal"

As can be seen in the way Roosevelt

attacked Hoover for his new government-spending programs – which is

exactly what Roosevelt would come quickly to advocate early on in

office – Roosevelt really did not have a specific set of plans in mind

to deal with the Depression as he took office in early 1933. In his

acceptance speech at the Democratic nominating convention in 1932

Roosevelt had talked about a "new deal" for the American people, though

he had not given any details as to what that might specifically be all

about. The idea "new deal" soon became the program "New Deal" (a term he

chose which sounded quite similar to his uncle Theodore's "Square Deal")

– and it meant whatever Roosevelt chose for it to mean as he struggled

forward to put policies into play that might solve the problem of the

Depression.

Roosevelt's "Brain Trust"

Whatever it meant specifically, it meant generally

that the national government was going to have to step into the realm

of the economy and take the lead in getting things moving again.

Roosevelt assembled an advisory council made up of a number of

intellectuals (originally a small group of Columbia University

professors, soon joined by a number of lawyers), that would come to be

known as Roosevelt's "Brain Trust." These economic and legal experts

would advise Roosevelt in ways to program the country out of the

economic mess it found itself in. They would be the ones to put actual

substance to Roosevelt's New Deal idealism.

One of the early projects during the

Roosevelt Administration's First-100-Days push was the National

Recovery Administration (NRA) set up in 1933. It was a voluntary

program that employers were supposed to engage in, promising that they

would observe certain minimum pricing schedules for their products (to

stop the competitive lowering of prices designed to drive the

competition out of business) – and help their workers by offering at

least minimum wages and maximum working hours. Those businesses which

signed on with the program were permitted to display the Blue Eagle

poster. But those that did not were often boycotted – and thus the

voluntary nature of the program was compromised. There were complaints

about this.

Roosevelt also in those First 100 Days

created the CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) to provide three million

jobs for young family men, building 800 national or state parks and

planting three billion trees. He put some price-control policies in

place (the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933) to help raise the

incomes of the American farmer, essentially by taking land and thus

crops out of production, thus raising the farmers' prices for their

crops (but also making food more expensive for everyone else). Also in

1933 he set up the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to control the

Tennessee River flowing through the heart of the American South,

offering not only flood control but also electrical generation and

transmission to the entire region, which previously had no electrical

service.

Supporting and regulating the banking and finance industry

In accordance with the Glass Steagall Act of 1933,

Roosevelt set up the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as a

guarantee to Americans that their bank accounts were protected by a

Federal insurance guarantee against bank failure – thus putting

confidence back into the American banking system (the FDIC is still in

operation today). The Act also prevented commercial banks (which

receive checking and savings deposits and extend loans to individual

Americans) from involvement in the realm of investment banks (which buy

and sell stocks, bonds and other securities). The next year, 1934, he

set up the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to put the stock

markets under federal regulation, to curb the excesses of speculation

that appeared to have caused the problems in the first place – and to

put confidence back into the American stock markets (the SEC is also

still in operation today). He also in 1934 created the Federal Housing

Administration (FHA also still in operation today) to insure home

mortgages and thereby stabilize the mortgage market.2

The growth of government as industrialist

He also, through the Works Progress

Administration or WPA of 1935, had the government move into the new

realm of state-directed industry: the building of national highways,

new libraries, government buildings, special camp and park facilities,

even hydroelectric power generating dams. He hired artists to paint

murals in public buildings and musicians and playwrights to compose new

music and plays. His program even paid women to sew.

Roosevelt also moved to strengthen

labor's position in the bargaining with the owners of America's major

businesses (The National Labor Relations Act or Wagner Act of 1935).

This gave a tremendous boost to the American labor movement ... and

made the labor unions very loyal to the Democratic Party after that.

And the New Deal set up a program of

basic social security for the elderly in their years of retirement (the

Social Security Act of 1935). The program also included unemployment

insurance and welfare support for the poor and handicapped.

2Unfortunately,

much of the regulatory work of the SEC and FHA was most unwisely cut

back by the Bush, Jr. administration in the opening years of the 2000s

– presumably to help free up a slowing economy. Actually, what it did

was to help produce, through the so-called "shadow banking system," the

subprime mortgage crisis which started in early 2007 and reached the

level of a major financial meltdown in September of 2008.

One of his first promises

fulfilled was the reversing of the 18th Amendment (Prohibition)

Hollywood celebrities toasting

the end of Prohibition – December 1933

Celebrating the end of

Prohibition

A thirsty Clevelander takes

a deep gulp of beer with the end of Prohibition in 1933

The other promise was to

put America back to work again – even if it took Government work to do

it

Harry L. Hopkins – Secretary

of Commerce, major architect of the New Deal ...

Harry L. Hopkins – Secretary

of Commerce, major architect of the New Deal ...

and close personal advisor

to Roosevelt

President Roosevelt confirming

Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor – and the first woman to sit

on a presidential cabinet – 1933

President Roosevelt confirming

Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor – and the first woman to sit

on a presidential cabinet – 1933

Frances Perkins

National Archives

NA-208-PU-155Q-38

FDR at the site of the future

Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River, Washington State – 1934

Civilian Conservation Corps

work site

Civilian Conservation Corps

work site

A WPA highway construction

project

National Archives

A WPA project: New

York City ferry boat

A WPA project: New

York City ferry boat

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project:

Electrification

of the Pennsylvania Railroad

A WPA project:

Electrification

of the Pennsylvania Railroad

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Pavilion,

Huntington Beach, California

A WPA project: Pavilion,

Huntington Beach, California

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Work

Shed – Grand Canyon National Park

A WPA project: Work

Shed – Grand Canyon National Park

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Mental

hospital, Camarillo, California

A WPA project: Mental

hospital, Camarillo, California

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: San

Francisco Fair

A WPA project: San

Francisco Fair

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Lincoln

Tunnel, New Jersey to New York City

A WPA project: Lincoln

Tunnel, New Jersey to New York City

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Gold

depository, Fort Knox,Kentucky

A WPA project: Gold

depository, Fort Knox,Kentucky

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Triborough

Bridge, New York City

A WPA project: Triborough

Bridge, New York City

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: The

Mall, Washington, D.C.

A WPA project: The

Mall, Washington, D.C.

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Prison

Farm, Tattnall County, Georgia

A WPA project: Prison

Farm, Tattnall County, Georgia

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Boulder

Dam, Colorado River

A WPA project: Boulder

Dam, Colorado River

By Ansel Adams,

Nevada

National Archives

A WPA project: Zoo,

Washington, D.C.

A WPA project: Zoo,

Washington, D.C.

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Swimming

Pool, Wheeling, West Virginia

A WPA project: Swimming

Pool, Wheeling, West Virginia

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Band

shell, Phoenix, Arizona

A WPA project: Band

shell, Phoenix, Arizona

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Water

tank, Sacramento, California

A WPA project: Water

tank, Sacramento, California

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: The

Jewel Box, Shaw's Garden, St. Louis

A WPA project: The

Jewel Box, Shaw's Garden, St. Louis

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

A WPA project: Federal

Trade Commission Building, Washington, D.C.

A WPA project: Federal

Trade Commission Building, Washington, D.C.

Public Works Administration

and Federal Works Agency

Increasingly, the nation

looked to FDR to lead them through the troubled times

These families, about to

lose their homes, appeal to President Roosevelt for aid

Part of his success in getting

the nation behind him was his way of taking his case to the American people

over radio

These families, about to

lose their homes, appeal to President Roosevelt for aid

Part of his success in getting

the nation behind him was his way of taking his case to the American people

over radio

FDR and his "fireside chat"

with the American people over the radio

FDR and his "fireside chat"

with the American people over the radio

Another part of his success

was due to the warmth and energy of his wife, Eleanor

Eleanor Roosevelt

Eleanor Roosevelt Foundation,

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Eleanor and

FDR

Eleanor Roosevelt visiting

a WPA work site in Covington, Georgia

Eleanor Roosevelt visiting

a WPA work site in Covington, Georgia

Things seem definitely to

be improving – and the nation registers its approval by re-electing Roosevelt

to office by a huge majority

The presidential election

of 1936

The presidential election

of 1936

Department of the

Interior

A CONSERVATIVE US SUPREME COURT TRIES

TO SHOOT DOWN FDR's NEW DEAL |

|

The New Deal runs into serious problems

Roosevelt's first term in office, especially his

First Hundred Days, saw the coming into existence of a massive number

of government economic programs. Roosevelt seemed the master of the

situation – and encountered relatively little opposition. But towards

the end of his first term, and in the early part of his second term,

Roosevelt found his programs coming under a lot of criticism – and even

determined opposition.

Criticism began to build about how his

New Deal was becoming simply creeping Socialism. There was also

mounting criticism about how many of these make-work programs were a

waste of taxpayers' money. Jokes and sneers arose about all the

standing around that seemed to accompany many of these work projects.

Problems with the Supreme Court

The biggest problem however was the

Supreme Court. By 1935 the Supreme Court was knocking down one program

after another of Roosevelt's New Deal for being unconstitutional.

According to the Supreme Court, there was no constitutional basis for

the national government to be meddling in the affairs that were clearly

reserved to the states as part of their jurisdiction.

The worst blow came on Black Monday (May

27, 1935) when the Supreme Court pronounced unanimously on three cases

– all of them going against Roosevelt's New Deal. The hardest of them

for Roosevelt to swallow was the Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States

case in which the Court declared that the NRA was unconstitutional. The

NRA, in violation of the constitution's design of the separation of

powers, had assigned legislative powers to the Presidency that belonged

alone to Congress. But also Congress's use of the interstate commerce

clause to justify the creation of the NRA program was clearly in excess

of the powers allotted Congress by the Constitution. But more such

anti-New-Deal decisions were to be handed down during the next year.

Roosevelt was so upset by this personal

rebuff by the Supreme Court that he decided to remake the ideological

character of the Supreme Court. In early 1937 he announced that he

would be introducing into Congress a new Judiciary Reorganization Bill,

expanding the number of the Court's justices. The political intent was

clear to all: he was looking to pack the Court, through the

presidential power of appointment, with enough new justices to swing

the Supreme Court rulings in his favor politically.

The

public reaction was negative, despite

Roosevelt's many efforts during the spring of 1937 to enlist popular

support for his idea. To the contrary. Opposition to the

idea grew with

the passage of time. Opposition in the House of Representatives

was

apparent from the outset, so Roosevelt introduced the bill into the

Senate instead. But the Senate dragged on in debate.

Eventually a split

began to open up between the president and the senators of his own

Democratic Party. Roosevelt was losing political ground fast.

But in the meantime, a switch of votes in

the Supreme Court had occurred, with one of the justices changing sides

from anti to pro New Deal, and another justice retiring, thus giving

Roosevelt the opportunity to make a new appointment. He now had a

voting majority without having to pack the Court. Roosevelt backed down

on his court-packing scheme. But he had lost a lot of political

standing in the process. Many Americans felt that Roosevelt was taking

notes from the highhanded ways of the European dictators, Stalin,

Hitler and Mussolini. Roosevelt not only had gambled personally and

lost in this contest, his attack on the Supreme Court also greatly

weakened his ability to continue the political reforms he felt the

country needed to undergo in order to get back to sound economic health.

Bad economic news continues

This event was also timed with another

slowdown in the American economy which hit in 1937, resulting in the

growth again in the number of unemployed Americans. 1938 was not any

better economically – and 1939 saw only a very slight economic

recovery. There seemed to be little that Roosevelt could do to get the

economy back on track again.

|

The U.S. Supreme Court -

1930

The U.S. Supreme Court -

1930

The U.S. Supreme Court in

session

The U.S. Supreme Court in

session

PERSISTENT DROUGHT ADDS TO AMERICA'S WOES BY CREATING THE MIDWEST "DUST BOWL" |

|

To make matters worse, during the entire 1930s,

but becoming incredibly intense in the mid-1930s, a deep and persistent

drought hit the Midwest states, worst in the Panhandle area of Texas

and Oklahoma, northwestern New Mexico, western Kansas, and eastern

Colorado – but extending all the way from central Texas in the south to

the Dakotas in the North. The topsoil was simply blown away by hot

winds which turned the air into black clouds of choking dust. Farms

were simply abandoned as destitute farmers headed west to California to

look for work – any work. Most of them ended up living in migrant

workers' camps under the worst conditions imaginable. People survived –

but only by toughening up tremendously.

With all of this happening to America,

Roosevelt found his popularity slipping during the latter part of the

1930s. He would not regain the popularity he had in the first of his

terms in office until the entrance of America into World War Two in

late 1941.

|

A dust storm in Texas -

1935

A dust storm in Texas -

1935

A dust storm about to envelope

Elkhart, Kansas – May 21, 1937

Prolonged drought throughout

the 1930s reduced the Kansas wheat fields to dust.

Library of Congress

LC-USZ62-35799E

One of the many dust storms

that hit the American Great Plains – 1932-1936

One of the many dust storms

that hit the American Great Plains – 1932-1936

Library of

Congress

Two Colorado girls still

able to draw water from a well amidst the storms raging

through the "Dust Bowl" – 1935

Dust Storm – by Arthur Rothstein

Dust Storm – by Arthur Rothstein

Library

of Congress

An abandoned farm in the

South Dakota Dust Bowl – May 1936

National Archives

NA-114-SD-5089

An abandoned farm in New

Mexico hit hard by the dust storms

An abandoned farm in New

Mexico hit hard by the dust storms

MIGRATION WEST TO CALIFORNIA TAKES UP IN

ERNEST |

"Dust Bowl" families heading

West

Library of

Congress

Oakie Family heading

West

(What's this? ... It looks like he just dropped his cell phone!!!)

Broken down on the road to

the West

Library of

Congress A family living out of their

flatbed truck – California – February 1935

A family living out of their

flatbed truck – California – February 1935

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

Migrant mother of Seven -

Nipomo, California – March 1936

Migrant mother of Seven -

Nipomo, California – March 1936

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

Migrant mother of Seven -

Nipomo,

California – March 1936

Migrant mother of Seven -

Nipomo,

California – March 1936

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

A migrant worker's family

in Oklahoma – 1936

A migrant worker's family

in Oklahoma – 1936

Library of

Congress

Heading west to California

in search of a better life

Library of

Congress

A young couple who had been

working the fields along Highway 99 in California's Imperial Valley.

A young couple who had been

working the fields along Highway 99 in California's Imperial Valley.

Dorothea Lange, November

1936

Library of Congress LC-USF34-16102

A Texas family living in

a tent in Exeter, California – 1936

Library of Congress

LC-12466-F34-9841

A family fleeing the Southwest

Dust Bowl to California

A migrant worker

shaving

Library of

Congress

Migrant workers'

shack

Migrant workers'

shack

Library of

Congress

Mother washing children's feet in a

sharecropper's shack in Missouri – May, 1938

Russell Lee

Library

of Congress

Family

who traveled by freight train – Washington, Yakima Valley – August 1939 Family

who traveled by freight train – Washington, Yakima Valley – August 1939

Dorthea Lange

Library

of Congress

An individual who plumbed

the depths of the American soul during this time was John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck

Tortilla Flat -

1935

Of Mice and Men -

1937

The Grapes of Wrath

- 1939

EVEN WITH THE IMPLEMENTATION OF FDR'S PROGRAMS, POVERTY REMAINS A SERIOUS PROBLEM IN MANY AREAS OF THE COUNTRY |

A Federal relief worker visiting

a Tennessee family in 1935

Daughters of a WPA worker

and a sick mother

Library of

Congress

"Cheap Auto Camp Housing

for Citrus Workers"

"Cheap Auto Camp Housing

for Citrus Workers"

Dorothea Lange, Tulare

County, California, February 1940

Riding the rails – Bakersfield,

California

1940

Riding the rails – Bakersfield,

California

1940

"ROOSEVELT'S NEW DEAL BROUGHT US

OUT OF THE DEPRESSION" ... YES OR NO? |

|

Actually, no! Not at all! It is common among

most Americans today to refer to how "Roosevelt's New Deal brought us

out of the Depression" when contemplating what to do in the face of a

new round of economic difficulties facing the nation. This popular myth

however is quite untrue. Certainly, the New Deal helped many idle

workers find work. It certainly built highways, dams, municipal

buildings, national parks, rural electrification, new rail services,

etc. Government projects were truly a blessing to many Americans

desperate to find work. But these projects did not solve the problem of

the Depression itself.

The American Free Market or "consumer" economy

America has long been a grass-roots

democracy not only in the area of government or politics, but also in

the very nature of its economy. Unlike most societies of the world

which throughout history have traditionally been driven by the economic

wants or goals of the rich and powerful – emperors, kings, aristocrats

and priests – the American economy has been built, since its origins in

the early 1600s, on the interests of very ordinary people. There have

been of course exceptions to this picture: the slave-holding South

prior to 1865 and the Gilded Age of the late 1800s dominated by the

captains of industry – or, as some would say, the industrial robber

barons. But in general, the American economic system has been built on

the labor, the product, and the economic desires of very ordinary

citizens.

The personal or private consumer is king

What determines what actually gets made

in America are the simple interests of the average American – known

simply as the American consumer. These interests of the American

consumer register themselves in what is termed the market place or free

market. The matter of what gets made, how much gets made, and what it

will cost, are all determined simply by how much interest the American

consumer has in a product when it goes to market. If it is a really hot

item, drawing strong consumer interest, it will enter the market place

quite pricey – and highly profitable to the producer. But other

producers with a typical American entrepreneurial spirit will want to

get into the act and also begin producing this highly profitable

product (or – under copyright laws – something somewhat like it) and

bring it to market – and themselves share in the blessings of high

profits. But this entrepreneurial urge will eventually be met with a

declining consumer interest – as most of the people who wanted these

hot items now are in possession of them (radios, cars, tractors,

washing machines, etc.). Unsold items will begin to pile up on the

market shelves. To move these items to sale, producers will attempt to

make these same products continue to be attractive – thus the American

advertising industry – but ultimately attractive through lower pricing.

Lower prices will help bring some additional consumers to the market –

but not at the rate that they were there when the item was hot.

At this point the producer has to make

some decisions. He can continue to make the product, though at a slower

rate – which means he is going to have to cut back on production and

let some workers go. He does not need their labor, and anyway, because

his products are not selling well and profits are way down, he cannot

afford to pay them.

Or – he can switch to a new product, even

a new line of products, simply to keep his business going. This means

he has to be inventive, imaginative – and a natural risk taker. He

needs to listen to the market, to the consumer, to sound the consumer

out in terms of possible interest in new products. He can also go to

advertising in an attempt to create consumer interest – by letting the

consumer know in written or broadcast advertising, in words, song, or

even drama, how wonderful life would be if the consumer only had his

new product!

But this is how the Free Market works.

The consumer is king. It's all very democratic. There is no political

authority dictating production or distribution or pricing according to

official decrees. In fact, the American free market system has

traditionally been highly suspicious of such governmental interventions

into the economic system (commonly termed a "Command Economy") and

tolerates only the slightest of such interventions under very special

circumstances, and only for a limited time.

For government intervention to go beyond

that would be to undermine the whole idea of the Free Market system –

and instead produce an economic system in which "enlightened" social

authorities decide for the people themselves what they are going to get

from the economy and how they are going to get it. This latter economic

system is termed "Socialism" or "Communism" (although Fascism has many

of the same characteristics.)

Dealing with the business cycle

Of course, as with all social systems,

this Free Market economic system is not without its problems. Market

saturation such as described above, when most consumers have these

products and therefore show a declining interest in them, is one of

these problems. This is a big part of what was happening to the

American economy at the end of the Roaring 20s. The market for consumer

products stopped roaring.

Because of this tendency of the market to

heat up as new products are brought to market – and then cool down as

the market becomes saturated – industrial production, and the economy

in general, tends to move in cycles of growth, maturity and decline.

Economists call this the business cycle. Economists have long attempted

to find ways to smooth out the peaks and valleys of the business cycle,

to make the economy steadier in its movement. But the very nature of the

Free Market system itself seems to make it immune from such efforts.

The famous English economist John Maynard

Keynes put forth the idea in the 1930s that the business cycle could be

modulated or smoothed by the government's interventions as the economy

goes through the various phases of a business cycle. He advocated a

governmental strategy of loosening money supply (creating more money

for the market to work with) during the cooling phase of the business

cycle and then tightening that money supply during period of a hot

market.

This Keynesian theory seemed to make a

lot of sense to a lot of economists – and to a lot of government

officials. In a sense Roosevelt's New Deal moved in accordance with

this theory. But whether it actually contributed to – or simply slowed

down – the recovery of the market economies in the 1930s remains even

to this day a matter of great debate.

What is not debatable is the fact that

what a Free Market truly needs to keep going or get back going if it

has slumped and fallen into idleness is new products. New products are

what bring the consumer back to the marketplace to do business.

In a sense the New Deal produced new

products – but products desired not by the individual consumer, but

collectively by the society, sometimes termed infrastructure items.

These items are vital to the society as a whole … but beyond the scope

of any individual or even group of individuals to produce or sell (or

even finance). The New Deal produced highways, parks, public buildings,

etc., social items certainly desired by the average American – but

products that no one single consumer would have ever been able to buy.

So in that sense the New Deal worked. Government-funded projects

certainly met important infrastructure needs of American society.

"Market saturation" for government products

(roads, dams, parks, etc.)

But even here part of the problem was

that the New Deal suffered from its own version of market saturation.

Under the New Deal a great number of national highways were built. But

once built, Americans did not need new ones to replace them right away.

Highway building slowed down. New dams were built at the most likely

spots where energy could be cheaply generated. After that, dam building

became much less cost effective. Dam building slowed to a halt. Parks

were built – until the need for park building was greatly reduced. In

short the government as producer was facing the same problem that the

private producer had faced at the end of the 1920s: market saturation

for government or social products. By the late 1930s, with the

government forced to slow up in its building projects, unemployment

began to rise again in America.

Government intervention into the economy

certainly had taken up some of the slack in an idle American economy

during a good part of the 1930s. And it had brought good things to

America. But it had not solved the basic problem of the Depression. The

American economy simply seemed to have no urge to take off again on its

own. That's because new personal consumer products were needed to bring

the American consumer, the bedrock of the American economic system,

back to market.

But coming up with a new line of products

to go to market with is not easy. It takes discovery, new technologies,

changing circumstances – many things that are not automatically brought

into being. And during the entire 1930s there really was no such

development of new product lines by private industry.

Some blame the New Deal itself for the

failure of new products, new technologies, to develop during the 1930s.

They claim that scarce investment funds were all used up by the

government to push its own economic agendas. Financial capital that was

needed to back up new inventions and new production was simply not

available to the private entrepreneur because it was all flowing to the

government. Perhaps this was true. But perhaps not. Clearly there was

another factor involved that unquestionably shaped the way the private

industrial system was to behave in the 1930s.

The New Deal put

money in the pockets of the workers that built all these New Deal

products. But what did the worker do with this money? In general, the

worker put it away in a safe place. The old adage is that he put it

under his mattress! Actually, he most likely put it in a savings

bank. Thanks to Roosevelt's FDIC insurance of bank deposits, a savings

bank was finally a safe place to put one's money. In any case he was

not going to put it in the stock market any time soon. He was still too

frightened about what might happen if he put his money there. So,

workers' wages were of little help in producing a revival of the

capital market which financed the business ventures of private

manufacturers.

The banks where he deposited his money

were of no help to the capital market either. And it was not just

because banks too had been scared away from involvement in that market.

Actually because of the Glass Steagall Act of 1933 it was illegal for

such commercial or depository banks to enter the capital market. Only

banks licensed as investment banks were permitted to trade in the

capital market. These were not the banks where the worker placed his

savings. Investment banks were not permitted to do this simple kind of

business. They were the banks you went to if you wanted to buy or sell

(or borrow – though with new limits) corporate stocks, bonds or other

kinds of corporate securities. Thus it was that workers' wages did not

usually translate themselves into new inputs into the capital markets

vital to the recovery of private industry.

In short, the average American wage

earner now suffered from the economic disease of lacking consumer

confidence in the market place. He earned his money – and then put it

away, where it would go unused in stimulating new market demands. And

thus the market continued to sit quietly while little happened in the

private economic sector.

World War Two finally brought America out of the Depression

World War Two finally brought America out

of the Depression. In the end what brought America out of the

Depression was not the New Deal – but was World War Two, which the

country embarked upon only at the very end of 1941. The war, and the

war alone, proved to be the factor that would put America back to work.

New products (uniforms, guns, fighter planes, bombers, tanks, trucks,

cannons, battleships, carriers, submarines, etc.) would be needed in

vast, virtually unlimited quantities. Every American that was not in

uniform would be needed to support the war on the home front – in

particular even young women working in the production and assembly

plants where these products were manufactured.

And there was no danger of market

saturation – at least until the war was over. Such products were

quickly destroyed in the action of war and thus immediately called

forth replacement products.

In the American economic system, the

government did not make these products. Private industrial

manufacturers did. Of course, the finished product did not need to go

to market. The government was the market – under contract to buy the

product as soon as it came off the assembly line. But as with the New

Deal economy, the average American was the financial underwriter of the

war economy. Part of this support was in the form of taxes paid to the

government – which Americans were quick to offer because this was their

war – not just their government's.

But taxes were not sufficient to cover

the huge government expenditures involved in this business of war. The

government needed to go into deficit spending – borrowing money now

with the promise to pay it back later, when the emergency of the war

was over. And who was the lender to the government? The American people

themselves. They lent to the government huge amounts of their personal

industrial earnings (created by war production) – in the form of war

bonds: contracts or certificates issued by the government which

promised the American lenders that they would be repaid in the future,

with nice interest earnings added. Purchasing war bonds turned the

average American into a capital financier lending to the government.

The possibility of guaranteed interest earnings was part of the

motivation. Besides, what was a person to spend his or her money on

anyway? Automobile manufacturers had turned to the business of making

army trucks and tanks. No automobiles were manufactured during the war.

Except for war goods there wasn't much of anything to spend your money

on anyway. Everyone was under rationing so you couldn't even go on a

food-spending splurge. So putting your money away in the form of war

bonds made natural sense. Besides, it seemed to be one's patriotic duty.

And that's how the American economy came

back to life. World War Two, not the New Deal, brought America finally

out of the Great Depression.

|

Go on to the next section: A Shift in the American Sense of Order

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | | |

Hoover's indecision

Hoover's indecision

The spiral downward of the American

The spiral downward of the American America and the world during the

America and the world during the The 1932 presidential election

The 1932 presidential election

Roosevelt: The story behind the man

Roosevelt: The story behind the man

The Depression has deepened as

The Depression has deepened as Roosevelt quickly sets out to institute a

Roosevelt quickly sets out to institute a The Supreme Court shoots down FDR's

The Supreme Court shoots down FDR's Persistent drought creates the Midwest

Persistent drought creates the Midwest Migration West to California takes up in

Migration West to California takes up in Poverty remains a serious problem

Poverty remains a serious problem "Roosevelt's New Deal brought us out of

"Roosevelt's New Deal brought us out of