PEOPLE OF IDEAS

THE WESTERN ENLIGHTENMENT

(Mid-1600s to Late 1700s)

By Alphabetical Order:

A

d'Alembert,

Jean

Le Rond

Allen,

Ethan

Astruc,

Jean

B

Bayle,

Pierre

Bengal,

Johann

Albrecht

Bentham,

Jeremy

Berkeley,

George

Bolingbroke,

Henry

Saint

Boyle,

Robert

Burke,

Edmund

C

Chauncey,

Charles

Condorcet

D

Descartes,

René

Diderot,

Denis

E

Edwards,

Jonathan

Eichhorn,

Johann

Friedrich

F

Fénelon,

François

Fox, George

Francke,

August

Hermann

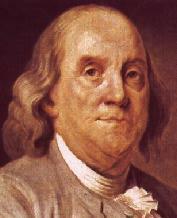

Franklin,

Benjamin

G

Gibbon,

Edward

Grotius,

Hugo

Guyon,

Madame

H

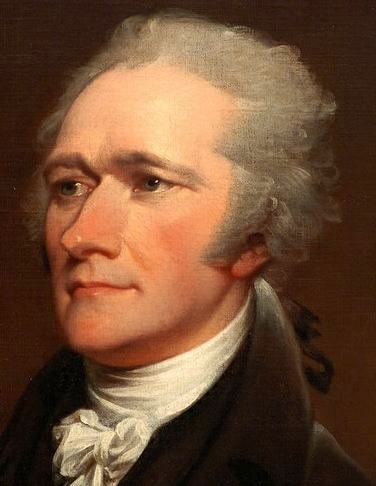

Hamilton,

Alexander

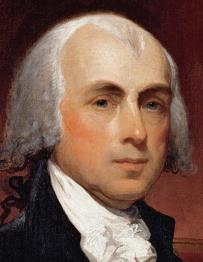

Harrington,

James

Helvitius

(Claude Adrien)

Herbert of

Cherbury,

Herder,

Johann

Gottfried

Herschel,

William

Hobbes,

Thomas

d'Holbach,

Baron

Hume,

David

Huygens,

Christian

J

Jefferson,

Thomas

K

Kant,

Immanuel

L

Laplace,

Pierre

Simon de

Law,

William

Leeuwenhoek,

Anton

van

Leibniz,

Gottfried

Wilhelm

Lessing,

Gotthold

Ephraim

Locke, John

Lowth,

Robert |

M

Malebranche,

Nicholas

Mather,

Cotton

Milton,

John

Montesquieu,

Baron

de

N

Newton, Isaac

P

Paine,

Thomas

Paley,

William

Priestley,

Joseph

R

Ray,

John

Reid,

Thomas

Reimarus,

Hermann

Samuel

Rousseau,

Jean-Jacques

S

Shaftesbury,

The

Earl of

Smith,

Adam

Spener,

Philip

Jacob

Spinoza,

Benedict

(Baruch)

Swedenborg,

Emanuel

T

Tennent,

Gilbert

Tindal,

Matthew

Toland,

John

Turgot

V

Vico,

Giambattista

Voltaire

(François-Marie

Arouet)

W

Wesley,

John

Wesley,

Charles

Wettstein,

Johann

Jakob

Whitfield,

George

Whitney,

Eli

Wolff,

Christian

Woolston,

Thomas

Z

Zinzendorf,

Count

Nikolaus

|

THE PLEA FOR TOLERANCE AND A JUST ORDER

(Mid-1600s) |

René

Descartes (1596-1650)

Galileo's and Kepler's work

coincided in its timing almost exactly with the work of another early 17th

century figure: René Descartes. In some ways Descartes was

a medieval rationalist – who believed (in keeping with Plato) that all things

in the world around us are merely "extensions" of some variety of mathematical

or geometric abstractions. The underlying truth about our world "out there"

was discoverable really only through careful mathematical meditations on

that world – which could be done at home or in one's closet. Galileo's and Kepler's work

coincided in its timing almost exactly with the work of another early 17th

century figure: René Descartes. In some ways Descartes was

a medieval rationalist – who believed (in keeping with Plato) that all things

in the world around us are merely "extensions" of some variety of mathematical

or geometric abstractions. The underlying truth about our world "out there"

was discoverable really only through careful mathematical meditations on

that world – which could be done at home or in one's closet.

But in any case, what he

came up with in his musings was the idea that the world "out there" was

essentially a mechanical device that worked according to fixed rules of

motion. Events occurred as the result of impacts among the various bodies

that are in constant motion within this "machine." The machine itself

is devoid of soul or vitality of its own. It simply responds to the "laws"

of motion in a mathematical way.

But that left the question

of the human soul and will – and the divine soul and will. Where do we fit

in? Are we merely elements of this mechanical world? Is God merely an element

of the mechanical world? To Descartes the answer was clearly a "no" to

both questions.

But in affirming our own

vitality – and God's – Descartes was forced to separate the human soul (and

God's) from that soul-less mechanical creation "out there." Fine. But how

then were we connected to that world – except as removed observers? Where

was our ancient sense of unity with all creation? Where in fact did that

leave us in relation to God – and to each other?

Those questions were never

adequately answered. The human soul seemed to be left cut adrift by what

was considered a very compelling philosophical statement – one which swept

powerfully through the philosophical circles of Europe in those days.

Descartes'

major works or writings: Descartes'

major works or writings:

Discourse

on the Method (1637)

Meditations on the

First Philosophy (1642)

Principia Philosophiae

(1644)

Benedict

(Baruch) de Spinoza (1632-1677)

Spinoza was born of Jewish parents

who had escaped the Inquisition in Portugal by coming to Amsterdam where

Baruch (Latin: Benedictus) was born. Spinoza was a very unorthodox

thinker – and his ideas eventually got him expelled from the Jewish community

(1656). Because he saw God as present in everything – as the source

and essence of all substance – he was viewed variously as a pantheist, a

materialist, an atheist.

He was a moral relativist,

who did not believe in some set of transcending religious or civil laws

that we ought to conform ourselves to, but who instead believed in following

out our own natural personal imperatives – that noone else had a right to

pass judgment on.

This was not a philosophy

designed to make the religiously conservative community around him very

happy. But it certainly spoke to those souls who

were tiring rapidly of the mean spiritedness of the religiously orthodox – a

growing number of youthful minds who hoped to rise

to truths which were vastly higher than the traditional variety that had

brought Europeans to war against

each other mercilessly.

Spinoza'

major works or writings: Spinoza'

major works or writings:

A Short Treatise

on God, Man and his Well-Being

Tractatus de Intellectus

Emendatione (Treatise On the Improvement of the Understanding)

(1661-1677)

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus(Treatise

on Theology and Politics) (1670)

Ethics (1663-1675,

1677)

Gottfried

Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

German mathematician and rationalist

philosopher – who, simultaneously with Newton, invented the differential

and integral calculus. He was a widely talented and travelled individual – and

kept up friendships and correspondences with a wide range of scientists,

philosophers and political figures of the day.

Leibniz was born and educated

in Leipzig, eventually studying law at the University of Leipzig.

From 1667 to 1672, he worked for the Elector of Mainz as a lawyer and diplomat.

He travelled widely coming

into close contact with a number of political and scientific luminaries

of his day. In 1762 me travelled to Paris where he came into contact

with Huygens, and Malbranche. His travels also took him to England

(1673, 1676) and to Amsterdam (1673), where he spent time with Spinoza.

During these days he began his work on the calculus.

In 1676 he went to work as

a librarian to the Duke of Brunswick, and took up work on a number of mechanical

devices that utilized his mathematical and technical talents. But

he also turned his attention to philosophy, completing works on metaphysics

and systematic philosophy during the 1680s and 1690s.

Leibniz'

major works or writings: Leibniz'

major works or writings:

Hypothesis

Physica Nova (New Physical Hypothesis) (1671)

Discours de métaphysique

(Discourse on Metphysics) (1686)

The New System

(1695)

Nouveaux Essais sur

L'entendement humaine (New Essays on Human Understanding) (1705)

Théodicée

(Theodicy) (1710)

The Dialogues of Hylas

and Philonous (1713)

The Monadology(1714)

Giambattista

Vico (1668-1744)

Italian philosopher of history

and society – though he also had wider interests in mathematics and linguistics.

Vico's

major works or writings: Vico's

major works or writings:

New Science

(Scienza Nuova)

|

|

THE EARLY EMPIRICISTS

(1600s) |

Robert

Boyle (1627-1691)

Robert

Boyle (1627-1691)

Boyle is considered the "Father"

of modern chemistry. He was one of the "virtuosi" of the Royal Society.

He viewed the scientific enterprise as a confirmation of the providential

hand of God. To him, science and theology did not contradict – but spoke

to one single truth in God.

Boyle's

major works or writings: Boyle's

major works or writings:

New Experiments

Physico-Mechanical (1660)

The Sceptical Chemist

(1661)

Christian

Huygens (1629-1695)

A Dutch physicist who made a

number of contributions to science in a number of different subfields.

He developed the pendulum clock, the telescope, and added to our knowledge

of the planet Saturn and its satellite rings and moons.

He is perhaps most notable

for his theory that light functioned as a wave rather than as particles

(in contrast to Newton). He claimed that light moved along a vibrational

path through invisible ether to reach the eye and produce vision.

Huygens'

major works or writings: Huygens'

major works or writings:

Horologium

oscillatorium (1658)

Systema Saturnium

(1659)

Treatise on Light

(1690)

Anton

van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723)

studied microscopic life

Isaac

Newton (1642-1727)

Toward the end of the 1600s

Newton picked up on Descartes' theories of motion and completed the mechanistic

vision of the universe that he had laid out. In his Principia (1687)

he so thoroughly pulled the mechanistic vision together that it became

the single most important foundation piece for the modern world-view.

He "demonstrated" that all

things within the universe are made up of minute bits of matter which are

held together in their shape and movement through the force of natural

attraction or gravity (the gravitational attraction of two bodies is equal

to the product of their mass divided by the square of the distance between

them). This theory explained quite fully everything from the movement of

the planets through the skies, to the movements of the tides, to the velocity

of falling objects – and more.

Just as importantly – the

completeness of the theory left no possibility of seeing creation as a

"living" thing. Creation was without life of its own; it was instead mere

"matter" responding mechanically to a set of fixed mathematical laws.

Nonetheless, Newton thought

of himself as being religiously quite devout. His theory of the universe

– so he thought – was intended as a powerful tribute to the Grand Architect

who designed such a wonderfully complex yet beautiful creation.

However, Newton depicted

God in such a way that God actually lost "personality" and the realm of

sovereign action. God was left a role in nature largely as "First Mover"

with no further significant intervention in life. God nearly became identified

with the eternity or infinity of the universe.

Newton's

major works or writings: Newton's

major works or writings:

Philosophiae

Naturalis Principia Mathematica (The Principia) (1687)

Opticks (1704)

Isaac Newtown's Papers

and Letters on Natural Philosophy [Collection] (ed. Cohen: 1952)

John

Locke (1632-1704)

Very shortly after Newton's

Principia

was published, Locke published his Essay on Human Understanding

(1690).

Locke brought the human mind

into this mechanical world by positing a theory of knowledge in which the

mind at birth is simply a blank receptacle, possessing no "innate" ideas.

Over the years the mind has data added to it from the outside world. This

comes in the form of "sensations" that strike this blank mind through the

sensory devices of sight, hearing, feeling, taste, and smell.

These data in turn are developed

into full ideas by the mechanism of the mind, which sifts this imported

information in the search for the agreement or disagreement of two thoughts

or idea. From this mental process develops a well articulated vision of

the world around us – and its causes and effects.

As far as "moral" ideas were

concerned, Locke felt that prudence and long-term self-interest would serve

the rational mind as the determiner of human action.

This theory of human knowledge

stood in strong distinction to the traditional understanding that the mind

possessed fully – even at birth – a vast store of innate understanding that

was vitally a part of its soul quality. The old theory accounted for "learning"

by seeing the task not one of inserting information from the outside (as

per Locke – and almost every Western educator since), but instead one of

drawing out (thus the ancient word "education" which means "draw out")

the wealth of innate understanding already present in the human soul. One

didn't make discoveries about things "out there." A person made discoveries

about things already located deep down inside oneself.

Though Locke's theory could

offer no hard evidence that what he hypothesized was indeed true – the time

was ripe for such a theory. "Science" was rapidly stripping life of the

sense of "soul" or "sacredness" to it. The wars of religion had also helped

immeasurably. So Locke's theory "made sense." That was all that was needed

to leave a lasting impression on the rapidly shifting world-view of the

West.

Locke's

major works or writings: Locke's

major works or writings:

Two

Treatises of Government (1689)

A

Letter Concerning Toleration (1689,

1690, 1692)

An

Essay on Human Understanding (1690)

Education (1693)

The Reasonableness

of Christianity (1695)

|

|

NATURAL" RELIGION (DEISM) AND

PHILOSOPHY

(Late 1600s to Early 1700s) |

Lord Edward

Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648)

He saw little role for revelation

in the quest for truth. He believed that all humans are naturally

endowed with intuitive ways that linked them to God through simple faith

and moral action. Human reason, not religious revelation, was then

a more reliable means of perfecting and fulfilling these natural,

intuitive ways.

Herbert is quite justly considered

the "father" of English deism.

Herbert's

major works or writings: Herbert's

major works or writings:

De Veritate

(On

Truth)

(1624)

De Causis Errorum

(On

the Causes of Errors)

(1645)

De Religione Laici

(On

the Religion of the Laity)

(1645)

De Religione Gentilium

(On

the Religion of the Gentiles)

(published posthumously in 1663)

Autobiography

(ending with the year 1624; published posthumously in 1764)

John Ray

(1627-1705)

An English Puritan and a botanist/biologist.

He made tremendous contributions to the work of classifying plant and animal

life into families by way of their structure.

As a devout Christian he

put forth the "argument from design" for the existence of God: viz.,

surely such precision and order in the natural life necessitated an intelligent

being as creator of the universe.

Ray's

major works or writings: Ray's

major works or writings:

Catalogus

Plantarum Angliae (Catalog of English Plants)

(1670)

Methodus Plantarum

Nova (1703)

Historia Plantarum

(3 vols: 1686-1704)

The Wisdom of God

Manifested in the Works of Creation(1691)

Pierre

Bayle (1647-1706)

A French philosopher living

in the Netherlands who was highly critical of traditional Christian doctrines

and teachings. In his Dictionary he lampooned Christian beliefs – and

called for toleration of all viewpoints, even atheism. He believed

that human reason, not religious revelation, was the only reliable source

of truth.

Bayle's

major works or writings: Bayle's

major works or writings:

Philosophical

Commentary on the Words of the Gospel (1686)

Historical and Critical

Dictionary (1697)

John Toland

(1670-1722)

Knowledge derived largely only

through human reason. There was only a very reduced role for divine revelation.

Toland opened the deistic controversy in England

Toland's

major works or writings: Toland's

major works or writings:

Two Letters

from Oxford

(1695)

Christianity not Mysterious

(1696)

Amyntor (1698)

Letters to Serena

(1704)

Adeisidæmon

(1709)

Nazarenus

(1718)

Pantheisticon

(1720)

Tetradymus

(1720)

The Primitive Constitution

of the Christian Church (1726)

Matthew

Tindal (1655-1733)

Tindal's

major works or writings: Tindal's

major works or writings:

Essay concerning

the Power of the Magistrate (1697)

The Rights of the

Christian Church asserted (1706)

The Nation Vindicated

(1711)

Christianity as Old

as the Creation (1730) [something of an official "Deist Bible"

in his time. Here Tindal lays out the argument that all that is valuable

in Christianity is that which universal reason alone would hold true.

All else (i.e. revelation) is superstition – the most evil form of subjugation

of the human mind.]

Thomas

Woolston (1670-1733)

Woolston debunked the miracle stories

of Jesus and the resurrection accounts in Scripture – on the basis of rationalist

arguments.

Woolston's

major works or writings: Woolston's

major works or writings:

Six Discourse on the

Miracles of Our Savior (1727-1729)

Two Defences (1729-1730)

The Earl

of Shaftesbury (1671-1713)

(Anthony Ashley Cooper)

He was interested in formulating

new sciences of ethics and of esthetics – based not on any kind of imposed

norm, such as divine command, but upon the "natural" inclinations of man.

His definition of the "good" or "desireable" was ultimately related to

that which makes a person truly "happy." In this sense he was part

of the newly arising age which began all logic from the point of view of

personal human experience. What was good or true was that which was

personally good and true for me.

Nonetheless he attempted

to anchor this self-centered ethic in loftier holding-ground. Thus

he related the notion of what it is that makes a person happy to certain

natural harmonies in human life. Such harmony was characterized by

a moderation in all things. Thus for instance the emotions were not

to be denied – but kept in their natural place by the power of human reason,

being allowed to arise only in a manner appropriate to their nature:

ie., anger only when and to the extent anger was reasonably appropriate.

He also tried to anchor this

self-centered ethic in our natural sense of conscience – which was a facet

of our social nature as humans. Thus human reason, which was

supposed to be the directing force in our lives, was closely connected

to our common human experience – and was not merely the result of our personal

inclinations to do this or that. In that sense also human "happiness"

was understood to be a part of life's natural harmony, a harmonization

of our personal inclinations with the larger social experience: ie.,

our instinct for "sympathy."

In any case nothing in his

moral-ethical or esthetic system depended upon "authority" for it to work.

It supposedly all flowed out of the natural instincts of human nature and

the harmonies those produced when allowed free play. This was quite

a radical challenge to the older Christian interpretation of human nature – with

its vision of original sin built into the human character. It moved

in a direction opposite Christianity's traditional view that goodness flows

out of God's judgments alone and finds its place in our midst only through

the discipline of God-fearing authority.

Shaftesbury's arguments seemed

so persuasive to the 18th century that his book Characteristics

(1711) underwent eleven editions during that century.

Shaftesbury's

major works or writings: Shaftesbury's

major works or writings:

Inquiry Concerning

Virtue or Merit (1699)

Characteristics

(1711)

Henry

St. John Bolingbroke (1678-1751)

Bolingbroke's

major works or writings: Bolingbroke's

major works or writings:

Letters on

the Study and Use of History (2 vols: 1735; published 1752)

Christian

Wolff (1679-1754)

|

|

REACTION TO "NATURAL" RELIGION OR DEISM

(Late 1600s to Early 1700s) |

ON-GOING CHRISTIAN PIETISM

(Late 1600s to Early 1700s) |

George

Fox (1624-1691)

founder of Quakers

Fox's

major works or writings: Fox's

major works or writings:

Autobiography

Philip

Jacob Spener (1635-1705)

German Pietist who attempted

to move the Christian life away from the Lutheran focus on the church's

ecclesiastical doctrine and sacraments – toward a personal relationship

with God through small group prayer and study of Scripture. He also

promoted a simple life-style and abstinence from certain social "frivolities"

(dancing, card-playing, theater-going) as a mark of piety.

Spener's

major works or writings: Spener's

major works or writings:

Pia Desideria

(1675)

August

Hermann Francke (1663-1727)

Francke

picked up on the pietist concept from Spener and amplified it by giving

it wide applications in the area of charity work. He was a German

university professor who was hounded from university to university by Lutheran

authorities until he was invited by Frederick I of Prussia to take up a

professorship at the new University of Halle. Here he helped developed

the university into a mainstay of German pietism – and gave pietism a missionary

quality. As a pastor in nearby Glaucha he also established an orphanage

and school (the Paedagogium) for poor children – the latter of which

eventually was schooling over 2,000 children. This became a model

for other pietist missions.

Madame

Guyon (1647-1717)

A Christian mystic: a

quietist who believed that total surrender of the human will to the will

of God, with an accompanying total indifference to the things of the world,

was the path to a perfect union with God.

She was born Jeanne-Marie

Bouvier de La Motte. At age 16 she married Jacques Guyon, Lord of

Chesnoy. He died 13 years later –and after a further 5-year period

of spiritual training under the quietist Friar François Lacombe,

she left her children and began travels in quest of her own spiritual perfection.

The Catholic Church intensely

disliked quietism (Lacombe was arrested in 1687 and died soon thereafter

in prison) and on two occasions she was imprisoned for her beliefs and

writings. The first period (1688) was brief, for Louis XIV's second

wife, Mme de Maintenon, intervened to have her released after only three

months in prison. But the church was adamant in its opposition of

quietism and in 1695 called her disciple, abbot Fénelon,

to make a defense of their works. However, quietism was offically

condemned by the church and Mme. Guyon was arrested – and held in prison

until 1703. She lived out the rest of her life in Blois, trying to

avoid attention yet continue her writings, which were voluminous. Mme.

Guyon's major works or writings: Mme.

Guyon's major works or writings:

Moyen court

et très facile de faire oraison

(The Short and Very Easy

Method of Prayer)

(1685)

Madame de la Mothe Guion

(Autobiography of Madame

Guyon)

François

Fénelon (1651-1715)

French Catholic quietist (condemned

in 1687)

Fénelon's

major works or writings: Fénelon's

major works or writings:

Spiritual

Progress

Les aventures de Télémaque

(1699)

Cotton

Mather (1663-1727)

Cotton Mather, son of the Puritan

minister and Massachussetts political leader, Increase Mather, became himself

the leading Puritan minister in Massachussetts at the end of the 1600s

and beginning of the 1700s.

He was a prolific writer

and researcher of wide interest – from modern science and medicine to witchcraft.

Like his father, he was particularly interested in shaping and directing

a model Christian (Puritan) commonwealth in Massachussetts. However

he himself lived long enough to watch with sadness as the once strong piety

of his countrymen faded into religious indifference.

At the same time, though

he was a deeply pious Puritan, he took on some of the ideas about God that

were gradually being put forth by the deists.

Mather's

major works or writings: Mather's

major works or writings:

Magnalia

Christi Americana (1702)

Bonifacius,

or Essays to Do Good (1710)

Curiosa

Americana (1712-24)

Christian

Philosopher (1721)

Count

Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf (1700-1760)

Sponsor of Moravians |

|

THE GREAT AWAKENING

(Mid-1700s) |

Gilbert

Tennent (1703-1764)

Tennent was a Presbyterian

"New Sider." He favored revival and opposed the Calvinist formalism

of the "Old Sider" Scotch-Irish Presbyterians of the middle colonies (Pennsylvania

and New Jersey)

|

|

CHRISTIAN MYSTICISM

IN THE AGE OF REASON |

Emanuel

Swedenborg (1688-1772)

Swedish scientist and mystic.

Swedenborg was born to a

Swedish family headed by a father who was a chaplain to the Swedish king,

a teacher of theology at the University of Uppsala – and later a Lutheran

bishop.

Swedenborg graduated from

the University of Uppsala in 1709 and travelled through Europe for the

next five years. He took a particular interest in mathematics and

the natural sciences and studied these subjects in England, Holland and

France, bringing him into contact with some of the notable mathematicians

and scientists of his day.

Upon his return to Sweden

he edited Sweden's first scientific journal,

Daedalus Hyperboreus. He

eventually took up minerology (serving for a lengthy period of time as

royal assessor at the Royal Board of Mines), branched from there to astronomy,

mathematics and scientific cosmology. His encyclopedic mind led him

in 1734 to publish Opera Philosophica et Mineralia.

Then he turned his thoughts

to physiology and psychology – in particular the workings of the brain and

how this connected to the "soul" of the person. Thus in 1740-1741,

during another trip abroad, he published in Amsterdam

Oeconomia Regni

Animalis (The Economy of the Animal Kingdom)

He then branched into the

study of language and symbolism – leading him eventually to come to the

view that "reality" was in fact a complex array of symbols corresponding

to deeper spiritual realities – a view not unlike that of Pythagoras and

Plato.

A deeply mystical religious

experience of his in 1743 led him to take note of his dreams and particular

visions – including visions of Jesus Christ (Journal of Dreams: 1743-1744)

. With the second of these visions of Christ, he gave his energies

over entirely to the pursuit of spiritual matters, in particular the ways

in which spiritual reality reveals itself symbolically in divine revelation.

He put this thinking to work

in his Arcana Caelestia (8 vols: 1749-1756), reviewing the first

five books of the Old Testament, the Books of Moses. His goal was

to demonstrate how a deeper spiritual reality flows beneath the natural

reading of the text – showing the correspondence between the two levels.

In 1758 he published his De Coelo et ejus Mirabilibus et de Inferno

(On

Heaven and Its Wonders and on Hell) – certainly his most well-known work. To Swedenborg, the fundamental

reality of all things was God – summed up as Divine Wisdom and Love.

Physical or natural reality was in fact an extension, an outworking of

these two elements of God. Human freedom and self-absorption had

over the aeons progressively damaged the relationship that had one existed

between man and God, corrupting human wisdom and love – until Jesus Christ

reopened the way back to full relationship, full correspondence between

human love and wisdom and Divine Love and Wisdom.

Even this too had become

corrupted – by the Christian community itself – pointing to the need of Christ's

second coming, which Swedenborg felt was at hand. The growth of the

enlightenment seemed to Swedenborg to point to the immediacy of this event.

Swedenborg felt that he had

been specially called by God to bring forth this good news – and saw his

own writings as a crucial part of this wonderful event of Christ's second

coming.

In his lifetime he had succeeded

in drawing around him devotees who in the next 10-20 years after his death

formed up religious associations known as the Church of the New Jerusalem

or New Church. His followers were also sometimes called "Swedenborgians."

But his influence extended well beyond this group of disciples – to many

within the Romanticist movement that began to emerge during the late 1700s

and which blossomed in the 1800s. In particular, Honoré de

Balzac, Charles Baudelaire, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Butler Yeats and

August Strindberg acknowledged an intellectual indebtedness to him.

Swedenborg's

major works or writings: Swedenborg's

major works or writings:

Opera Philosophica

et Mineralia (3 vols: 1734)

Oeconomia Regni Animalis

(The Economy of the Animal Kingdom) (2

vols: 1740-1741)

Journal of Dreams

(1743-1744)

Regnum Animale

(The Animal Kingdom)

(2 vol.: 1744-45)

The Worship and Love

of God

Arcana Caelestia (Heavenly

Arcana) (8 vols: 1749-56)

De Coelo et ejus Mirabilibus

et de Inferno (Heaven and its Wonders and Hell From Things

Seen and Heard) (1758)

Amor Conjugialis (Conjugal

Love) (1768)

Apocalypsis Explicata

(Apocalypse Explained)

(4 vol: 1785-89)

Vera Christiana Religio

(True Christian Religion)

(1771) |

|

LATER DEISM AND EARLY BIBLICAL

CRITICISM

(Mid to Late 1700s) |

Johann

Jakob Wettstein (1693-1754)

A Biblical scholar in Basel/Amsterdam.

Wettstein's

major works or writings: Wettstein's

major works or writings:

Prolegomena

ad Novi Testamenti graeci (1730)

outlining his ideas on text-criticism used eventually to produce his Greek

NT (1751-1752)

Libelli ad Crisinatque

Interpretationem Novi

Testamenti which stressed the importance of understanding the historical

setting for the life of Jesus and the apostles; also stressed the importance

of the study of rabbinic literature as an aid in proper exegesis of the

Gospels.

Johann

Albrecht Bengal (1687-1752)

Bengal's

major works or writings: Bengal's

major works or writings:

Gnomon Novi

Testamenti

(1742) a pietist's use of text-criticism and philological

study to explore the deeper or hidden meanings of Scripture as a devotional

aid.

Jean Astruc

(1684-1766)

Professor of medicine at Paris

Astruc's

major works or writings: Astruc's

major works or writings:

Conjectures

sur les memoires originaux (1753)

[literary analysis (use of different names for God, etc.) seems to point

to two main sources for Genesis, plus two secondary sources and signs of

the presence of a dozen other documents in its composition.]

Robert

Lowth

bishop of London

Lowth's

major works or writings: Lowth's

major works or writings:

De Sacra Poesi

Hebraeorum (1753) applied his knowledge of Greek and Latin poetry

to the study of Hebrew poetry, not only with reference to technical aspects

of the language (parallelism, etc.) but also to the poetic spirit of the

material.

Hermann

Samuel Reimarus (1694-1768)

professor at Hamburg

Reimarus'

major works or writings: Reimarus'

major works or writings:

Fragmente

des Wolfenbuttelschen Ungenanten (published post-humously by Lessing

in 1774-1778) Reimarus "defended" the faith through a deistic affirmation

of creation as the true miracle of God; the other miracles stories of Scripture

are demeaning of God's grandeur – only fraudulent accounts of religious

enthusiasts.

Gotthold

Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781)

Lessing equated the progress

of the human race with the progress of the individual from childhood through

youth to manhood. The Old Testament belongs to the childhood of man:

teaching strict rules of imposed discipline. The New Testament belongs

to the youth of mankind: teaching self-sacrifice and self-discipline in

favor of future success and benefits. Manhood is characterized by

duty, without immediate rewards: it is guided solely by reason – though

God may yet send new revelation to aid in the development of this stage

of human existence. In any case, though Scripture is invaluable in

our early development – it is less useful (belonging to an inferior past)

in guiding the present. Human reason is a higher guide.

Lessing's

major works or writings: Lessing's

major works or writings:

Education

of the Human Race (1780)

Johann

Gottfried Herder (1744-1803)

The clergyman Johann

Gottfried Herder studied under Kant at Königsberg ... but moved away

from Kantian rationalism into a mystical world presided over by

God. As a young pastor he met Goethe, inspiring the latter with

his insights into Biblical literature. He recognized that the

Hebrew literature of the Old Testament was more of the nature of poetry

and folk narrative than technical science (which was how rationalist

Western society was coming to think and operate at that point) ... and

that it was necessary to understand the Hebrew writings as such in

order to comprehend their great ‘truths.’

The two men

became good friends whose speculations together about human knowledge

birthed the Sturm und Drang (Storm and Drive) movement of the 1770s,

elevating human emotions above human intellect. Eventually their

thinking would settled down a bit and evolve towards Classicism, or

love of the styles of classical or ancient Greco-Roman antiquity in an

attempt to balance human emotion and human intellect.

Herder

was a strong German nationalist ... at a time when Germans were

attempting to construct the idea of a German nation (Germany at the

time was divided into hundreds of independent states, large and

small). Yet he was cautious about letting the highly emotional

spirit of nationalism get too far away from practical reason.

Then

with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 Herder would support

the Revolution, producing a split between himself and many of his

friends, including Goethe. Finally his dedication to refuting

Kant’s theories would place him pretty much in isolation within the

German academic community.

Herder's

major works or writings: Herder's

major works or writings:

Vom Geist

der Ebräischen Poesie (1782-1783)

disclosed how the Hebrew writings were written in a poetic vein (typical

of the ancient Near East) and had to be read as such – not technically (the

way moderns were tending to write and think)

Joseph

Priestley (1733-1804)

chemist; unitarian clergyman

William

Paley (1743-1805)

Paley put forth a "natural-theology"

defense of God based upon the self-evident complexity of the world – the

logic that such a beautiful creation could not be the result of anything

else except an all-powerful, all-caring God. He uses the analogy

of the watch: the complexity of a watch automatically or necessarily

points to the existence of a watch-maker. God is the "watch-maker"

of the universe.

Paley's

major works or writings: Paley's

major works or writings:

Natural Theology

(1802)

Johann

Friedrich Eichhorn (1752-1827)

Professor at Göttingen

Eichhorn's

major works or writings: Eichhorn's

major works or writings:

Einleitung

ins Alte Testament (1770-1773)

Ueber Mosis Nachrichten(1779)

both were major works on literary-criticism of the Old Testament

|

THE FRENCH

PHILOSOPHES

(Mid to Late 1700s) |

Baron

de Montesquieu (1689-1755)

Montesquieu's

major works or writings: Montesquieu's

major works or writings:

Spirit

of the Laws (1748)

Voltaire

(François-Marie Arouet) (1694-1778)

Voltaire's

major works or writings: Voltaire's

major works or writings:

Candide

The Philosophical

Dictionary

Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712-1778)

Rousseau was French philosopher (actually he was French-cultured Swiss) whose writings, especially The Social Contract

(1762), were very popular in France. He raised the question of

political sovereignty – where it was lodged and how it functioned to

best serve the people.

Rousseau claimed that originally

man lived in some kind of simple natural state of harmony, without laws

or government. But life had evolved over time into a more complex

form – civilization – requiring as it developed greater mutual

dependence among men for the orderly working of society ... and thus

also a more complex system of moral instruction or law to guide this

more complex society. Man accordingly had to give up his total

personal sovereignty to come under the protection and nurture of more

complex society. But he was giving it up not to some ruling

individual but to the larger idea of the society as a whole, the

‘general will’ – in particular its laws, which were the clearest

expression of a people’s general will.

The laws, not any

particular individuals, were the locus of sovereignty in the truly good

society. Unfortunately ignorance of this good had clouded

people’s political understanding – allowing them to slip into all forms

of political tyranny.

Rousseau’s hope was to open men’s

eyes to the understanding of what was truly right and good about

society, that such knowledge would free men to usher in a good or

utopian society that was truly their right to enjoy. All the

superfluous fru-fru of decadent civilization (in particular French

civilization as it was viewed in his own time) would be simply swept

away by the opening of the eyes of the people to the truth.

With

the Ancien Régime (Old Order) thus swept away, society would be free to

create or contract a social system as simple and basic as possible, a

social system directed by a set of basic laws that restored to man his

fundamental liberties, allowing him to live as close to the original

state of nature as possible.

The French were strongly impacted

by Rousseau’s theories – as have been many ‘revolutionary’ Secular

philosophers since Rousseau. The French monarchy was sick, very

sick. Reform was needed. But by Rousseau’s logic, that

reform was going to have to be extensive for the good society to

result. The Old Order was going to have to be set aside in its

entirety in order to make way for the new. Thus with Rousseau’s

encouragement, the French political mood was ‘revolutionary’ as the

political debate in the late 1700s intensified in France.

Rousseau's

major works or writings: Rousseau's

major works or writings:

Discourse

sur l'inegalism (Discourse on Inequality) (1754)

Du

contrat social (Social Contract)(1762)

Emile (1762)

Confessions (1782)

Denis

Diderot (1713-1784)

Diderot's

major works or writings: Diderot's

major works or writings:

Essai sur

le merite et la vertu (1745)

Pensees philosophiques

(1746)

Lettre sur les aveugles

(1749)

Encyclopedia

Helvitius

(Claude Adrien) (1715-1771)

Helvitius'

major works or writings: Helvitius'

major works or writings:

De l'esprit

(Essays on the Mind) (1758)

De l'homme (A Treatise

on Man) (2 vols.: 1772)

Jean

Le Rond d'Alembert (1718-1783)

French mathematician, physicist

and philosopher of science. His interests and talents in science

were widely spread – and he wrote extensively for Diderot's Encyclopedia

on various scientific subjects.

d'Alembert's

major works or writings: d'Alembert's

major works or writings:

Mémoire

sur le calcul intégral (1739)

Mémoire sur

la réfraction des corps solides (1739)

Traité de dynamique(1741)

Traité de l'équilibre

et du mouvement des fluides(1744)

Réflexions

sur la cause générale des vents (1747)

Essai d'une nouvelle

théorie sur la résistance des fluides (1752)

Recherches sur différents

points importants du système du monde (1754-1756)

Eléments de

philosophie (1759)

Eléments de

musique théorique et pratique (1779)

Baron

d'Holbach

Holbach's

major works or writings: Holbach's

major works or writings:

System of

Nature

Turgot

(1727-1781)

Turgot's

major works or writings: Turgot's

major works or writings:

Discourse

on the Successive Progress of the Human Spirit

(1750)

Condorcet

(1743-1794)

Condorcet's

major works or writings: Condorcet's

major works or writings:

Essai sur

l'application de l'analyse à la probabilité des décisions

rendues

à la pluralité des voix (1785)

(Essay on the Application

of Analysis to the Probability of Majority

Decisions)

Vie de M. Turgot

(1786)

Vie de Voltaire

(1789)

Esquisse

d'un tableau historique des progrès de l'esprit humain (1794)

(Sketch

for an Historical Table of the Progress of the Human Spirit)

|

THE ADVANCE OF REASON AND SCIENCE

(Mid to Late 1700s) |

Thomas

Reid (1710-1796)

Reid was a founding member of

the Aberdeen Philosophical Society and creator of the school of thought

known as Scottish Common Sense Realism.

Adam

Smith (1723-1790)

Smith was a Scottish economist,

born in 1723 – and died in 1790.

He early demonstrated strong

philosophical apttudes and was thus in 1740 awarded a scholarship to attend

Oxford University. However his strong devotion to the theories of

Hume brought him constant trouble while at Oxford – and also made difficult

his efforts to secure a teaching job upon graduation (and later, his efforts

to gain professional recognition among fellow academicians).

In 1762 he sttepped down

from his position at Glasgow University to become a tutor – and to begin

the writing of his work, The Wealth of Nations.

In this work he formulated

the key theories of market-driven economics (capitalism). He believed

in an "invisible hand" that would establish a balanced pricing structure

for all goods and services, simply through the natural competition of these

goods and services for buyers in an open or free market. Smith

was strongly opposed to any kind of "intervention" into this market mechanism

by the government or any other "outside" societal institution.

But by the same logic, Smith

was highly opposed to market "insiders" getting together to conspire to

set prices through a witholding of goods of services to create an artificial

scarcity. He was thus opposed to cartels, monopolies, unions.

He considered the danger

of rapid population growth distorting the labor market and driving prices

down to subsistence levels. But he felt that economic growth of the

whole industrial sector would constantly increase the demand for labor

and thus prevent such cruelties from occurring.  Smith's

major works or writings: Smith's

major works or writings:

The Theory

of Moral Sentiments (1759)

The Wealth of Nations

(1776)

Jeremy

Bentham (1748-1832)

Bentham

is considered to be the founder of British Utilitarianism ... a

philosophy built simply on the idea that "the greatest happiness of the

greatest number is the true measure of right and wrong." In

short, he was a strong advocate in favor of "human rights."

He was highly opposed to slavery, believed in equal rights for women,

was a strong advocate of the separation of church and state, was

opposed to physical punishment, and believed strongly that there

should be no restrictions on speech. He even supported the idea

of animal rights. But he spent his greatest energies on the matter of

prison reform. In short, he was a very "modern" philosopher and

jurist!

But he did not believe that all of these came simply by lifting

traditional Christian moral standards ... as if these "human rights"

would come into place on their own in a rather natural manner (as did

Marx and other philosophers that came after him). To him, human

rights would come only through proper moral and political reform of

society ... enlightened social reform – principally by enlightened

public authority.

Most interesting, someone he would undertake to raise to

these social ideals, John Stuart Mill, would later reject deeply Bentham's

ideas. Mill would disagree strongly with

Bentham that social progress would come best through the process of well-constructed

government action … Mill holding to the later developing idea that social

progress would fare better under personal or private development than under official

governmental action … which to subsequent British Liberals was central to their

idea of the critical importance of personal freedom.

Bentham's

major works or writings: Bentham's

major works or writings:

Fragment on

Government (1776)

Principles of Morals

and Legislation (1789)

The Theory of Legislation

(1802)

The Book of Fallacies

(1824)

William

Herschel (1738-1822)

An English astronomer – noted

in his day for the excellence and size of the telescopes he built – and

the careful observations he (with his sister Caroline) made of the heavens.

He began his career as a

musician – but became interested in optics and astronomy early in his career.

Until 1779 this was considered only a side-line – when a member of the Bath

Literary and Philosophical Society discovered his work with telescopes

and invited Herschel to present his work to the Society. He soon

became a member of this Society – and began to devote himself to astronomy.

In 1781 while scanning the

heavens with one of his powerful telescopes, he discovered a new planet

in the solar system – far beyond even Saturn. The Planet came to be

named "Uranus." This discovery brought him entry into the British

Royal Society – and a new position as personal astronomer to King George

III.

It was Herschel who, through

his persistent effort to count stars, came to conclude that the sky was

full of huge disk-shaped wispy clouds which were actually star clusters

of millions of stars each. Our sun was part of such a star cluster – the

rest of which we observed as the Milky Way.

All of this made it very

clear to him that the universe was vastly larger than we hitherto

had even come close to imagining.

Pierre

Simon de Laplace (1749-1827)

Isaac Newton had outlined the gravitational theories designed to demonstrate that the planets

moved about the sun in accordance to immutable mathematical principles.

There were however still unexplained small variations in Newton's computations:

he had not taken into account the gravitational attraction also working

among the planets themselves. These small variations had the ability

to destabilize the Newton's mechanistic model of the solar system.

But Newton was enough of a mystic to look to God to regulate the small

variations so as to keep the whole system in order.

This idea of a small residual

Divine intervention was not a satisfying concept to Laplace. He understood

the universe to be totally operative under the impersonal laws of nature.

So in 1773 he set out to give full mathematical explanation to the motions

of the heavens – in such a way that there would be no more need to call

in "God" as the residual part of the equation. This he successfully

did through an unprecedentedly in-depth mathematical calculation of the

eccentricities in the planetary orbits – taking into account their gravitation

attraction to each other as well as to the sun as they moved through their

respective orbits. (This work was eventually compiled into the five-volume

study: Traité de mécanique céleste/Celestial Mechanics.)

Laplace's work earned him

a place in the prestigious French Academy of Sciences. It also removed

the idea of God further (if not completely) from the mechanistic cosmology

that had been unfolding over the previous century. Not even deism

could stand up to this assault. Indeed, the story goes that when

Laplace presented a copy of his work to Napoleon, the latter uttered a

concern that Laplace had made no mention in his work of the Divine "Originator"

of this marvelous system – to which Laplace replied: "I had no need

for that hypothesis!"

From his understanding of

the dynamics of the attractions of any particle circling around a central,

attracting point, Laplace speculated that the solar system had come into

being through a similar gravitational force. He theorized in Exposition

du système du monde/The System of the World (1796) that

the cosmos had begun as nebular gas, and the gravitational concentrating

of matter had over the aeons gradually produced a concentrating of this

gas into a number of mass bodies which today make up the solar system.

Over the years of his study

he had worked carefully in developing the "probabilities" of the occurrence

of events over time. His work in this area he published in 1814 as

Essai

philosophique sur les probabilités/A Philosophical Essay on Probability.

In this study he lifted mathematics from an absolutist accounting of events

to a more accurate "probabalistic" accounting of those events. Thus

Laplace became a major contributor to the growing field of statistics.  Laplace's

major works or writings: Laplace's

major works or writings:

Exposition

du système du monde (The System of the World)

(1796)

Traité de mécanique

céleste (Celestial Mechanics)

(5 vols: 1798 - 1827)

Essai philosophique

sur les probabilités

(A Philosophical Essay on Probability)

(1814)

Eli Whitney

(1765-1825) Eli Whitney

(1765-1825)

American inventor of the cotton

gin and the idea of mass producing parts that could then be used interchangeably

in the production of tools and weapons. |

|

HUMANISM

(Mid to Late 1700s) |

SKEPTICISM / CRITICAL REVIEW OF

REASON

(Mid to Late 1700s) |

David

Hume (1711-1776)

Hume was a Scottish empiricist – well

known for his skepticism and sharpness of thought. Being a freethinker,

he was easily critical of thinking which rested on no other basis

than traditional argument. He also was sharply critical of thinking

which did not arise from the observation of actual behavior (empiricism)

but which was merely speculative in nature (rationalism). Hume was a Scottish empiricist – well

known for his skepticism and sharpness of thought. Being a freethinker,

he was easily critical of thinking which rested on no other basis

than traditional argument. He also was sharply critical of thinking

which did not arise from the observation of actual behavior (empiricism)

but which was merely speculative in nature (rationalism).

Yet at the same time he was

a quietly confident and serene individual who was deeply comfortable with

the world – and rather conservative in his social and political views.

Even his own skepticism was tempered by his understanding of the human

need for some kind of underpinning of custom or tradition in life.

His major philosophical thrust

was against the rationalists who were prone to build great intellectual

edifices on the foundations of some "self-evident" truths. He considered

such intellectualism as being highly dangerous – likely to lead to polemical

excesses (as the highly intellectually charged revolutions of France in

1789 and Russia in 1917 were certainly to prove in the years after Hume).

To Hume, custom – which was the sum of actual human experience – was the

only healthy foundation on which to build human life.

Being an empiricist, he was

impressed with the patterns by which people actually lived out their lives.

Hume felt that we should pay close attention to the human record of our

actual or "natural" (as he put it) behavior in order to draw conclusions

about life. Hume on the other hand was most unimpressed by the great

intellectual "spins" that philosophers wove around hypothetical behavior

in building their great systems of thought. For Hume reality was

in the doing, not in the hypothesizing about life.

Thus we remember Hume for

his skepticism about our views on God, our great systems of religious truth,

the validity of "objective" ethical systems, even the claims of science

to have established an explanation of all life in terms of cause and effect.

All this was to Hume mere intellectual humbuggery.

Hume's impact lived long

after him. In fact it was Hume that awoke Kant from his "intellectual

slumber" (as Kant himself put it) and caused Kant to undertake the task

of responding to the challenge that Hume had issued to those who would

claim to understand human nature, even life itself.

Hume's

major works or writings: Hume's

major works or writings:

A Treatise

on Human Nature (1739)

Essays, Moral and

Political (2 vols.: 1741-1742)

An

Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748)

Political Discourses

(1751)

Five Dissertations

(1756)

Essays

On Suicide And The Immortality Of The Soul

The Natural

History of Religion

Of Tragedy

Of

the Passions

Four Dissertations

(1757)

History of England

(6 vols.: 1754-1762)

Dialogues Concerning

Natural Religion(1777)

Immanuel

Kant (1724-1804)

Complicated in thought but simple

in life-style, Kant – who wrote and taught on a broad range of subjects

from physics to metaphysics, from theology to philosophy – lived out his

life in the relative confines of his hometown of Königsberg, East

Prussia ("Kaliningrad" since its Russian takeover towards the end of World

War Two).

In many ways Kant's intellectual

life was shaped by the challenge that Hume had issued the world a quarter

of a century earlier. In his

Critique of Pure Reason (1781),

Kant agreed with Hume's empiricism – namely that sense-experience is essential

to human knowledge. But he also agreed with the continental rationalists

(most notably Leibniz – whose writings also were a major influence over

Kant) that knowledge is also a matter of the exercise of human reason – in

particular the use of innate human ideas ("categories") which help us to

organize this empirical information. Thus Kant saw himself as closing

the intellectual gap between the British empiricists and the Continental

rationalists.

Kant also saw himself as

answering Hume's skepticism about ever knowing with any degree of certainty

the truth of transcendent ideas, such as moral laws or ethical principles.

In Kant's Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and Critique of Practical

Reason (1788), he proposed a new moral/ethical "categorical imperative,"

one that did not require the existence of God for its validity. And

yet Kant's concept was of a definite transcendant nature, one with absolute

universal validity. It involved an ingenious piece of moral logic:

we ought to act in such a way that our act could become accepted as a universal

principle of behavior. If it were not able to attain such a universal

validity (because, for instance, of an internal contradiction in logic)

then that action, by "practical reason," was obviously not to be pursued.

Taking this logic of "practical

reason" a step further, he turned to the issue of the existence of God.

He agreed with Hume that no rational argument could be given for God's

existence – that is, "pure reason" could not build a case for God's existence.

But "practical reason" could. Pursuing a traditional line of reason

that went back at least as far as Ockham in the early 1300s, Kant claimed

that human reason cannot establish the "fact" of God. But in observing

the moral instincts of people we can see (through the eyes of faith) that

there is some kind of source beyond the mere human will itself

that directs life. That higher moral grounding is by definition God.

Thus God exists. (This kind of theological reasoning did not impress

the Prussian government, which cenured his work).

Finally – so impressed was

Kant that we humans could live in accordance with such higher moral imperatives

that in his Perpetual Peace he laid out a vision for a new world

order.

Kant's

major works or writings: Kant's

major works or writings:

Critique of

Pure Reason (1781)

Prolegomena to Any

Future Metaphysics (1783)

Fundamental Principles

of the Metaphysic of Morals (1785)

Critique of Practical

Reason (1788)

The Critique of Judgment(1790)

Perpetual Peace

(1795)

Religion within the

Limits of Reason Alone

|

|

AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE ...

AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

(Late 1700s) |

THE EUROPEAN ENLIGHTENMENT:

A FULL HISTORY |

Go on to the next section: The 19th Century

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

The Dutch jurist, Hugo den Groot

(Grotius) appealed to the European conscience to seek a new spirit of openness

or tolerance about matters of Truth, a broad-mindedness about inquiry concerning

Truth.

The Dutch jurist, Hugo den Groot

(Grotius) appealed to the European conscience to seek a new spirit of openness

or tolerance about matters of Truth, a broad-mindedness about inquiry concerning

Truth.

Eli Whitney

(1765-1825)

Eli Whitney

(1765-1825) Edward

Gibbon (1737-1794)

Edward

Gibbon (1737-1794)