PEOPLE OF IDEAS

THE 19th CENTURY

(1800s)

By Alphabetical Order:

A

Alexander,

Archibald

Ampère,

André-Marie

B

Bauer, Ferdinand

Christian

Becquerel,

Antoine

Henri

Bell,

Alexander

Graham

Bergson,

Henri

Bessel,

Friedrich

Wilhelm

Blake, William

Blavatsky,

Helena

Petrova

Booth,

William

and Catherine

Bousset,

Wilhelm

Briggs,

Charles

A.

Browning,

Elizabeth

Barrett

Browning,

Robert

Burckhart,

Jakob

Christoph

Byron, George

Gordon Noel

C

Cannon,

Annie

J.

Carey,

William

Carlyle,

Thomas

Champollion,

Jean François

Chateaubriande,

François René, de

Coleridge,

Samuel Taylor

Comte,

Auguste

D

Dalton,

John

Darwin,

Charles

Dickens,Charles

Dilthey,

Wilhelm

Dostoevsky,

Feodor Mikhailovich

Durkheim,

Emile

E

Eddy,

Mary

Baker

Edison,

Thomas

Alva

Emerson,

Ralph

Waldo

Engels,

Friedrich

Evans,

Arthur

F

Faraday,

Michael

Feuerbach,

Ludwig

Fichte,

Johann

Gottlieb

Finney,

Charles

Fitzgerald,

George

Forsyth,

Peter

Fourier,

Charles

Fraunhofer,

Joseph

von

Frege,

Gottlob

G

Gladden,

Washington

Goethe,

Johann Wolfgang von

Green,

Thomas

Hill

Gunkel,

Hermann

H

Harnack,

Adolph

von

Hegel,

Georg

Wilhelm Friedrich

Hertz,

Heinrich

Hodge,

A.

A.

Hodge,

Charles

Husserl,

Edmund

Huxley,

T.

H.

J

James,

William

K

Kierkegaard,

Søren

Kirchoff,

Gustav

Robert

L

|

M

Mach,

Ernst

Maistre,

Joseph

de

Malthus,

Robert

Manning,

Henry

Edward

Marx,

Karl

Maxwell,

James

Clerk

Mendel,

Gregor

Mendeleyev,

Dmitry

Ivanovich

Michelson,

Albert

Mill,

James

Mill,

John

Stuart

Miller,

William

Moody,

Dwight

L.

Morley,

Edward

N

Newman,

John

Henry

Nietzsche,

Friedrich

O

Ørsted,

Hans

Christian

P

R

Rauschenbusch,

Walter

Renan,

Ernst

Ricardo,

David

Ritschl,

Albrecht

B.

Royce,

Josiah

Ruskin,

John

Russell,

Charles

Taze

S

Saint-Simon,

Count

Henri de

Schelling,

Friedrich

Schiller,

Friedrich von

Schliemann,

Heinrich

Schleiermacher,

Friedrich

Schopenhauer,

Arthur

Shelley,

Percy Bysshe

Smith,

Joseph

Smith,

William

Robertson

Spencer,

Herbert

Spurgeon,

Charles

Haddon

Strauss,

David

Friedrich

Sunday,

William

(Billy) Ashley

TTaylor,

E.

B.

Tennyson,

Alfred

- Lord

Thoreau,

Henry

David

Tolstoy,

Leo

Torrey,

R.A.

Treitschke,

Heinrich

von

W

Warfield,

Benjamin

B.

Webb,Sidney

Weber,

Max

Weiss,

Johannes

Wellhausen,

Julius

White,

Ellen

Whitman,

Walt

Wilberforce,

William

Wordsworth,William

Wrede,

Wilhelm

Y

Young,

Brigham

Young,

Thomas

|

EMPIRICISM AND POSITIVISM |

Robert

Malthus (1766-1834)

English economist and demographer.

Took the pessimistic view that all industrial growth would be more than

offset by an even faster rate of growth in the number of the poor.

Since the publication in 1798 of the book An Essay on the Principle of Population by

the English clergyman Robert Malthus, there was considerable discussion

in England about the problems created by a rapidly expanding human

population on the earth ... the issues of hunger, disease and war that

this would produce.

As an Anglican clergyman, Malthus wrested

with the problem of why God would allow suffering to occur within his

creation. Malthus finally concluded that God wanted man to rise

to the challenge of life, to succeed in the face of life’s difficulties

through the discipline of hard work. Those who fell short of the

challenge were simply some kind of disappointment to the great

Creator. Those who ‘failed’ merely reaped that which they had

sown.

Malthus'

major works or writings: Malthus'

major works or writings:

Essay on Population

(1797)

David

Ricardo (1772-1823) David

Ricardo (1772-1823)

Ricardo's

major works or writings: Ricardo's

major works or writings:

Principles

of Political Economy (1817)

James

Mill (1773-1836)

Mill's

major works or writings: Mill's

major works or writings:

Analysis of

the Phenomena of the Human Mind (1829)

Essay on Government

Auguste

Comte (1798-1857)

Comte reacted to the sometimes

wild speculation of French rationalists, who during the previous century

had built their philosophical theories on "reasonable" proposition – rather

than on the observation of actual phenomenon. In short, he introduced

British empiricism to French or continental philosophy, terming his approach

"positivism."

He was particularly interested

in seeing social philosophy built on very careful observation of actual

social behavior rather than mere rationalist speculation (such as Rousseau's

social theories a half-century earlier). Thus he laid the groundwork

for the field of modern sociology with its demand for "factual" foundations

for all assertions of truth.

But interestingly, in laying

out his arguments, he himself employed a very rationalistic or speculative

theoretical foundation for his assertions. In his major six-volume work,

Course

of Positive Philosophy, he posits an evolutionary development of human

knowledge over the aeons – a developmental picture that was entirely speculative – and

related more to a simplistic reading of the events surrounding Revolutionary

France over the course of the past century.

He stated that human knowledge

began in its primitive stages as theology, or laying all events at the

feet of divine forces or God (related to the Divine rights claims of monarchical

authority). The next stage, the rationalist or philosophical stage

was once characterized by broad abstract principles as the foundation of

truth or knowledge (he had in mind the rhetoric of Revolutionary France).

But the evolved state of knowledge (a pragmatic, bureaucratic post-Revolutionary

France) would be built on the works of scientific scholars who would direct

society through their knowledge of science.

None of this was itself based

on the empirical methods he called for in his study – but was itself a continuation

of the French rationalist approach to knowledge.

Nonetheless his ideas would

catch the imagination of 19th century Europe and help move it toward the

notion that all truth is built on fact and fact alone.

Comte's

major works or writings: Comte's

major works or writings:

Systeme de

politique positive (1823) and (1851-1854)

Cours de philosophie

positive (Course of Positive Philosophy) (1830-1842)

A General View of Positivism

(Chapter I: Its Intellectual Character) (1856)

John

Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

J.S.

Mill was an amazing child prodigy, reading classic Greek literature

(from Aesop to Plato) by age 8, then a full array of Latin and Greek

works by age 10 ... plus history, math, physics and astronomy. In

all of this, he was carefully "home schooled" – pruned

and protected in his infancy and youth by his father, James Mill – in

order

that the son would be "associated" only with the sharpest minds (his

father's and that of the family friend Jeremy Bentham) ... and not with

lower social orders of his own age ... a key part of the educational

philosophy of the British "Positivist" movement. His father's

goal was to grow his son into "a bright light of Utilitarian philosophy

that might light the world." In part the father succeeded, though

at a deeply heavy emotional and spiritual cost to the son.

Utilitarianism, Positivism, or Liberalism – all amounted to pretty much the same thing: holding the common view that a person is born with no a priori thoughts or abilities ... but as a thinking creature is simply the result of careful development by guiding hands –

hopefully ones that care deeply for the happiness of those in their

care. It was all very personal. Liberals (both Americans

and British, from Jefferson to the Mills) viewed with great distrust

the intervention of public authorities in this process. In short,

"the best government is the one that governs the least!" This

would be a central tenent of Mill's Utilitarian or Liberal philosophy.

The understanding was that simply a person becomes what the surrounding

world brings to that person ... nothing more, nothing less.

Therefore that surrounding world – physical as well as social – must

be carefully shaped, engineered, protected. But this must be

carried out on a personal or individual basis ... not on a public or

Socialistic basis. Personal freedom was essential to proper development.

However ... he was closely connected with the British administration of India – being a high-ranking official from 1823 (at age 17!) all the way to the end of the East India Company in 1858. In this matter, he

would, take a broader view of the responsibilities that fell to more

enlightened social hands in face of a "barbarian" society.

Something akin to social action or "benevolent despotism" would be

required under such circumstances ... but must be carefully conducted

so as to benefit and not just merely subdue such a barbarian society..

And

as far as an issue under much discussion at the time, Mill felt that

religion was the highly laudable ability of human thought to

rise above the merely physical or natural condition of life to

contemplate

and be moved by ideals of excellence. But whether there was a

supreme

Deity or consciousness to which human thought draws itself – or which energizes

the forces of life as Creator and Sustainer – was a most uncertain proposition for Mill.

In any case, the very

simplicity and the very attractiveness of Utilitarian or Positivist

"Liberalism" would catch on widely in the fast-changing political

setting of 19th century Britain. And Mill, with his many

publications, would be one to give great clarity and appeal to this

idea ... also helping to make the British Liberal Party a growing force

in British politics.

J.S.

Mill's major works or writings: J.S.

Mill's major works or writings:

System of

Logic (1843)

Principles of Political

Economy (1848)

On Liberty

(1859)

Representative Government

(1861)

Utilitarianism

(1863) (Wiretap)

Three Essays on Religion

(1874)

C.S.

Peirce (1839-1914) C.S.

Peirce (1839-1914)

coiner of the term "pragmatist"

William

James (1842-1910) William

James (1842-1910)

American pragmatist

James'

major works or writings: James'

major works or writings:

Radical Empiricism

The Will To Believe

(1897)

|

|

Johann

Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

Goethe was an individual of

wide tastes and talents, being a poet, dramatist and scientist all in one.

He was early influenced by Herder, who inspired in him a deep appreciation

of German folk culture and consequently a spirit of German nationalism.

But Goethe was also a profound

individualist, intrigued by the power and depth of personal experience

and emotion. In his first play,

Götz von Berlichingen

(1773), Goethe explored the depths of individual human sentiments – and

laid the foundation for the Sturm und Drang movement – which advocated

personal freedom in the face of oppressive, medieval attitudes in Germany

concerning the role of the individual in society. This movement would

later blossom into German Romanticism.

In

the 1780s Goethe went to Rome to study classic art, architecture and

literature and for a while came under the more formalistic style of the

neo-classicist movement. But on his return to Germany he found

little appreciation for his new views. He then turned to science for a

while. But his longer-standing romantic inclinations reasserted

themselves and his independent individualist style returned to the

fore. This culminated in his all-time great work, Faust (actually

written and rewritten in two parts over a long period of time reaching

perhaps from 1772 to 1829) ... which was an epic tale of the search of

the individual for that which is of a lasting or transcending value in

the face of freedom's great opportunities – and uncertainties.

His

Faust would be the best read work of German literature (roughly

equivalent to the place Shakespeare has long enjoyed in English

literature) ... inspiring young Germans for generations to quest for

the German ideal, the romantic spirit or soul that made Germany unique

among the nations.  Goethe's

major works or writings: Goethe's

major works or writings:

Götz

von Berlichingen (1773)

The Sorrows of Young

Werther (1774)

Wilhelm Meister's

Apprenticeship (1796)

Faust (1808)

Wilhelm Meister's

Travels (1821)

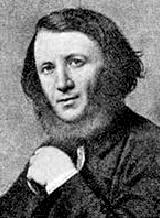

Friedrich

von Schiller (1759-1805)

Schiller was a German dramatist

and poet who contributed heavily to the

Sturm und Drang movement.

His own arrest in 1782 by the Duke of Württemberg for leaving Württemberg

without ducal permission to attend the performance of his first play, Robbers,

in another German state no doubt played an important role in shaping his

views on this matter. His close friendship with Goethe was also an

important source of inspiration for his politically charged dramatic works,

which dignified the instincts of the sensitive, heroic individual over

the heavy-handedness of traditional authority and social tradition.

Schiller's

major works or writings: Schiller's

major works or writings:

The Robbers

(1781)

Don Carlos(1787)

Wallenstein

(1799)

The Maid of Orleans

(1801)

William Tell

(1804)

Vicomte

François René de Chateaubriande (1768-1848) Vicomte

François René de Chateaubriande (1768-1848)

Chateaubriande's

major works or writings: Chateaubriande's

major works or writings:

The Genius

of Christianity (1802)

Memoirs from Beyond

the Tomb (1849-1850)

Aleksandr

Pushkin (1799-1837)

Considered the father of modern

Russian literature – for it was he who dared to write in Russian, the language

of the commoner, rather than, say in French, which was considered the language

of the upper classes or aristocracy. His thinking was considered

very revolutionary and he was dismissed from governmental service and banished

to his family's rural estate (he was rehabilitated two years later).

Pushkin's

major works or writings: Pushkin's

major works or writings:

Eugene Onegin

(1823)

Boris Godunov

(1825)

Eugene Onegin

(1823-1831)

Poltava (1828)

The Bronze Horseman

(1833)

The Captain's Daughter

(1836)

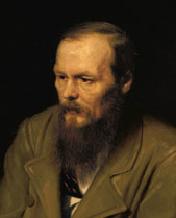

Feodor

Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881) Feodor

Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821-1881)

Dostoevsky's

major works or writings: Dostoevsky's

major works or writings:

Notes from

Underground (1864)

Crime and Punishment

(1866)

The Brothers Karamazov

(1879-1880)

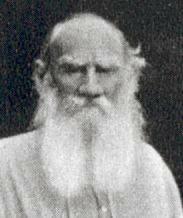

Count

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) Count

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910)

Russian Christian

Tolstoy's

major works or writings: Tolstoy's

major works or writings:

War and Peace

(1869)

Anna Karenina

The Death of Ivan

Ilych (1886)

William

Blake (1757-1827) William

Blake (1757-1827)

Blake's

major works or writings: Blake's

major works or writings:

The William Blake

Archive (poetry and paintings)

The William Blake Page

(poetry and paintings)

Collected Works

Selected Poems

William

Wordsworth (1770-1850) William

Wordsworth (1770-1850)

As with many English intellectuals,

Wordsworth as a young man was enthusiastic about the French Revolution

(1789) at least in its early stages. In 1791 he journeyed to France to

witness this grand event. But as time passed, and as the Revolution

turned bloodier and more vindictive and aggressive, he became distrustful

of the Revolution.

As a Romantic, he became

more enamored with the pathos of individual human life, especially the

nobility of the deeper human emotions – and less sure about the utility

of the rationally ordered society.

Wordsworth's

major works or writings: Wordsworth's

major works or writings:

Lyrical Ballads

(1798)

Written in cooperation with Coleridge – and considered the beginning of

the

Romanticist movement in England.

The Excursion

(1814)

The White Doe of Rylstone

(1815)

Ecclesiastical Sonnets

(1822)

The Prelude

(1850)

An autobiography started a half-century earlier – though not published as

a

completed work until after his death

Samuel

Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) Samuel

Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

Coleridge's

major works or writings: Coleridge's

major works or writings:

Biographia

Literaria (1817)

Selected Poetry and Prose

of Samuel Taylor Coleridge

George

Gordon Noel, Lord Byron (1788-1824)

A profoundly moody English Romantic

writer, he was considered by many of his English contemporaries to be almost

insane. He finally left England in 1816 to live on the European continent

as an English expatriate (he never returned). He wrote of individuals

who suffered deeply from the cruelties of society, heroizing the individual

who dared to stand on his own.

Byron's

major works or writings: Byron's

major works or writings:

Childe Harold's

Pilgrimage (1812)

The Prisoner of Chillon(1816)

Don Juan (1821)

Selected Poetry and Prose

of George Gordon, Lord Byron

Selected Poems of Lord

Byron

Percy

Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

A Romantic "non-conformist"

with a disdain for the conventional social mores of his times (he was expelled

from Oxford University for publishing a work, "The Necessity of Atheism").

A very productive poet who authored numerous odes from the time he was

26 until just before his 30th birthday when he drowned in sailing accident

during a storm.

Shelley's

major works or writings: Shelley's

major works or writings:

"The Necessity

Of Atheism" (1811/1813)

Prometheus Unbound

(1820)

In Defence of Poetry

(1822)

Complete Poetical Works

of Percy Bysshe Shelley

Selected Writings

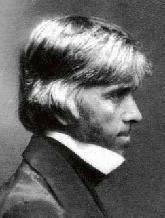

Thomas

Carlyle (1795-1881) Thomas

Carlyle (1795-1881)

Elizabeth

Barrett Browning (1806-1861) Elizabeth

Barrett Browning (1806-1861)

E.B.

Browning's major works or writings: E.B.

Browning's major works or writings:

An Essay on

Mind (1826)

Prometheus Bound

(1833)

The Seraphim and Other

Poems (1838)

The Cry of the Children

(1842)

Sonnets from the Portuguese

(1845-1850)

Aurora Leigh

(1857)

Poems Before Congress

(1860)

Alfred,

Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) Alfred,

Lord Tennyson (1809-1892)

English Poet Laureate, 1850-1892.

Tennyson's

major works or writings: Tennyson's

major works or writings:

Poems, by

Two Brothers (1827)

Poems, Chiefly Lyrical

(1830)

Poems (1833)

Poems (2 vols

1842)

The Princess, a Medley

(1847)

In Memoriam

(1850)

Maud (1855)

The Idylls of the

King (a continually expanding collection: 1859-1885)

Tithonus (1860)

Enoch Arden

(1864)

Lucretius

(1868)

Queen Mary

(1875)

Harold (1876)

The Falcon

(1879)

Ballads and Other

Poems (1880)

The Cup (1881)

The Promise of May

(1882)

Becket (1884)

Tiresias, and Other

Poems (1885)

Locksley Hall, sixty

years after (1886)

Demeter, and other

poems (1889)

The Death of ÃÂnone,

and other Poems (1892)

The Foresters

(1892)

Robert

Browning (1812-1889) Robert

Browning (1812-1889)

Robert

Browning's major works or writings: Robert

Browning's major works or writings:

Paracelsus

(1835)

Sordello (1840)

Dramatic Lyrics

(1842)

Dramatic Romances

and Lyrics (1845)

A Soul's Tragedy

(1846)

Christmas Eve and

Easter Day (1850)

Men and Women

(2 vol. collection of poems, 1855)

Dramatis Personae

(1864)

The Ring and the Book

(1868)

Dramatic Idyls

Asolando (1889)

Charles

Dickens (1812-1870) Charles

Dickens (1812-1870)

English novelist.

Dickens'

major works or writings: Dickens'

major works or writings:

Sketches by

Boz (1836)

The Pickwick Papers

(1837)

Oliver Twist

(1837-1839)

Nicholas Nickleby

(1838-1839)

The Old Curiosity

Shop (1840-1841)

Barnaby Rudge

(1841)

American Notes

(1842)

Martin Chuzzlewit

(1843-1844)

A Christmas Carol

(1844)

The Chimes

(1844)

The Cricket and the

Hearth (1845)

Pictures From Italy

(1846)

Dombey and Son

(1847-1848)

Battle of Life

(1848)

The Haunted Man

(1848)

David Copperfield

(1849-1850)

Bleak House

(1852-1853)

Hard Times

(1854)

Little Dorrit

(1855-1857)

The Frozen Deep

(with Wilkie Collins, 1856)

A Tale of Two Cities

(1859)

Great Expectations

(1860-1861)

Our Mutual Friend

(1864-1865)

The Mystery of Edwin

Drood (1869-1870)

John

Ruskin (1819-1900) John

Ruskin (1819-1900)

An English philosopher in search

of an uncerstanding and definition of beauty (aesthetics).

Ruskin's

major works or writings: Ruskin's

major works or writings:

The Seven

Lamps of Architecture

Walt

Whitman (1819-1892) Walt

Whitman (1819-1892)

Whitman's

major works or writings: Whitman's

major works or writings:

|

|

Ralph

Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

Emerson is best known as leader

of the "transcendentalist" movement in America. Emerson is best known as leader

of the "transcendentalist" movement in America.

He was born into a prominent

Boston family, one characterized by generations of service to the church

(his father, William, was the minister of the venerable First Church of

Boston). He attended Harvard College and Divinity School and eventually

became pastor of the 2nd church of Boston – where he soon achieved recognition

as an excellent preacher.

But like his father before

him, he found himself being drawn into new realms of thought that challenged

his orthodox Christian beliefs. The writings of the English romantics,

Carlyle and Coleridge, the philosophy of Swedenborg, the new biblical text-criticism

coming out of Germany, plus his own cool intellectual rather than warm

pastoral nature began to distance him emotionally from his work.

Soon after his wife died

in 1831, he stepped down from the ministry (1832) – to freely pursue the

question of the nature and purpose of human life – and its relation

to the larger natural world around man. He traveled to Europe, visiting

Coleridge, Wordsworth and Carlyle in the process. When he returned

to the States in 1833, he began work on his small, but revolutionary book,

Nature – which

he published anonymously three years later. In this book he outlined

the basic ideas that underpinned his Transcendalist philosophy.

Basically he took the ancient

Idealist position of Plato – in strict opposition to the mechanistic-materialist

philosophy of Newton and Locke which he saw as undergirding modern life

(including the Unitarian theology that was so prevalent around him).

He was in part a mystic (in keeping somewhat with the older Puritan tradition!) – seeking

direct knowledge of God through divine revelation, rather than through

systematic theology or rational philosophy.

He felt that Newton had imprisoned

the human spirit within his model of life as a machine made up of bits

of matter in motion in accordance to a fixed system of natural laws.

Further, he felt that Locke had only added to this error by depicting the

human mind as a similar machine, linked only to the outside world through

the the bombardment of external sensations upon the receptors of the mind.

This mechanistic-materialistic philosophy was all lacking the force of

spirit, a transcending spirit – which was to Emerson the substance

that gives rise to all life, human and otherwise. To Emerson, this

transcending spirit unites all life into a single harmony which flows from

God – and at the same time is God.

The moral implications of

Emerson's philosophy were in the vast freedoms this spirit seemed to give

man – freedoms to make choices about his own life. To Emerson man

was not a machine, but part of the great flow of the power of God – and

capable of fulfilling the most noble visions endowed by God to the active

human mind/spirit. Indeed, the human spirit was potentially so powerful

that it had a proper place in the on-going unfolding of all creation.

The human mind was thus not the victim of a supposedly machine-like environment

around it – but was instead its natural master, inasmuch as man acted in

harmony with that environment.

The Unitarians responded

with denunciations – especially when he brought his ideas before the Harvard

Divinty School in an address to that body in 1838.

Emerson had built up such

a faith in the natural attraction of the human mind to high-minded ideas

that he was a bit taken aback when his ideas failed to persuade – but only

stirred animosity. He learned the hard lesson that reform of human

life was not going to take place just in the presenting of ideas.

There was going to have to be concerted action that accompanied these ideas.

Though Emerson himself would not become an activist-reformer, many of his

close associates in the Transcendalist movement would – especially those

closely involved in the Abolitionist movement (to end slavery in the United

States).

He spent the rest of his

life serving as a lecturer, philosopher and poet – in wide demand on the

lecture circuit, even being called to Harvard to present his ideas.

He was definitely a man of the times, philosopher of the young, optimistic

American Republic which felt that it had a mandate to show the rest of

the world the higher, more humane way to live.

Emerson's

major works or writings: Emerson's

major works or writings:

Nature

(1836)

Essays: First Series

(1841)

["History," "Self-Reliance," "Compensation," "Spiritual Laws," "Love,"

"Friendship,"

"Prudence," "Heroism," "The Over-Soul," "Circles," "Intellect," and "Art."]

"The Transcendentalist"

Essays: Second Series

(1844)

["The Poet," "Manners," and "Character."]

Poems (1846)

Representative Men

(1850) [lectures]

The Conduct of

Life (1860) ["Power," "Wealth," "Fate," "Culture"]

May Day and Other

Pieces (1867)

Henry

David Thoreau (1817-1862) Henry

David Thoreau (1817-1862)

Thoreau's

major works or writings: Thoreau's

major works or writings:

Civil Disobedience

(1849)

Walden: Life in the

Woods (1854)

|

Johann

Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814) Johann

Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814)

Fichte's

major works or writings: Fichte's

major works or writings:

Versuch

einer Kritik aller Offenbarung (1702)

Grundlage der gesammten

Wissenschaftslehre (1794 )

Die Bestimmung des

Gelehrten (1794)

Grundlage des Alaturrechts

(The Science of Ethics) (1796)

Die Bestimmung des

Menschen (1800)

Grundzuege des gegenweirtigen

Zeitalters (1806)

Ueber das Wesen des

Gelehrten (1806)

Reden an die deutsche

Nation (Advice to the German Nation) (1808)

Die Wissenschaftslehre

in ihrem allgemeinen Umrisse (The Science of Knowledge) (1810)

Georg

Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831)

A General Overview

While the English were pushing

ahead an empirical doctrine of evolution through accidental natural causes,

the Germans were developing, through the primary inspiration of Hegel,

an "idealist" doctrine of evolution through the will of some great transcendent

will (the world Spirit). Hegel was clearly a Platonist – seeing all

history, all human events as "guided" by this powerful spirit. This task

of learning or of science was to Hegel (and the Hegelians after him) therefore

not just to collect facts, but to discern the particular movement of this

guiding hand in the midst of such facts.

Hegel was born and educated

in Stuttgart in the classics and attended the University of Tübingen

in preparation for the ministry. During the course of his university

studies he befriended Schelling – and decided against the ministry.

He found work tutoring, first in Switzerland then in Frankfurt. In

1801 he returned to his studies, this time at the University of Jena – where

he eventually became a lecturer, then department head. Here he completed

his first work, Phenomenology of the Mind – just in time to flee

Jena from the approaching French armies (1806).

He briefly turned to journalism

and then became director of a gymnasium in Nuremberg. During

his Nuremberg years (1808-1816) he compiled his Encyclopedia of the

Philosophical Sciences, incorporating his earlier Science of Logic

(1812),

and Philosophy of Nature and Philosophy of Spirit.

In 1816 he became a professor

at the University of Heidelberg; moving two years later to become a professor

at the University of Berlin, where he remained until his death in 1831.

In Berlin he published his Philosophy of Right (1821). After

his death his lecture notes were compiled into a number of publications:

Philosophy of Fine Art (1835-38), History of Philosophy (1833-36), Philosophy

of Religion (1832), and Philosophy of History (1837).

Hegel's Great Influence

on European Philosophy

Hegel was clearly a Platonist – seeing all history, all

human events as "guided" by this powerful spirit. This task of learning

or of science was to Hegel (and the Hegelians after him) therefore not

just to collect facts, but to discern the particular movement of this

guiding hand in the midst of such facts.Hegel and Kant.

For a while Hegel was strongly influenced by the philosophy of Kant –

especially the notion that the real basis of Christianity was not in

the legalistic religious doctrines evolved over the centuries by the

Christian church – but in the inherent moral "Reason" contained in the

teachings and example of Jesus. But ultimately it was not the

"moral reason" of Jesus that inspired Hegel but instead the idea that,

in and through Jesus as revelation of the divine, the Spirit of God had

spoken to the human heart of eternal truths. These were much

loftier and idealistic concepts than Kant's moral principles.The quest for union with God.

At the heart of Hegel’s philosophy was this idea of man’s hunger to

know – and be embraced by – God (or ‘Absolute Spirit’).

For Hegel

Jesus represented the goal for all humans: union with God (bringing a

divine embrace or condition of full love) – a human goal

much loftier than simply a rational understanding of the material world

around us ... which rationalist philosophers (such as Kant) pursued.

Hegel

saw this journey, this quest for full union with God, occurring in all

of life in progressive stages, from the simple to the complex.

This pertained not only to a person’s individual life, but to whole

peoples or nations ... in fact to everything alive in this universe.

For

example in his 1806 work, Phenomenology of the Mind, Hegel focused on

the evolutionary development of human thought, through the stages of

mere consciousness, then self- consciousness, then reason, then spirit

and religion, and finally to absolute knowledge. Here the human

mind comes to know itself as pure spirit – in its union with the pure

spirit of the Absolute. This is what Christianity, as presented

by Jesus, is ultimately all about.Knowledge

of the sense-world (achieved through modern science) around man is only

a starting point for Hegel in the development of human

consciousness. Scientific or rational knowledge standing as the

final goal of human study was to Hegel a false or deceptive completion

of the process of development. Such knowledge regrettably acts

only analytically – separating the objects of knowledge into discreet

categories. It also separates, even isolates, the human Geist

(mind or spirit) from the reality around it. While such reason is

materially useful to human life, it is not itself the highest or

ultimate attainment of the human spirit. That comes in a

process of unification – not separation – of the human consciousness

with the reality around it. Along

the way in the process the human mind passes through several stages of

development: from mere consciousness to a maturer

self-consciousness, to the realm of reason, but then also to the stage

of connection with the larger realm of reality through revealed

religion and its formal declarations, to. The dialectical struggle. Then in 1877, based on his

lecture notes, he published a new ground-breaking work, Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Outline. Undergirding

this work was the motif of struggle (Kampf)

– struggle of the human spirit or mind through various trials to

reach or fulfill itself in a higher union with God. But Hegel

also explained how God, from his side of things, also reached out to

the struggling human spirit ... by becoming himself human (and thus

limited) – to struggle alongside man to overcome the finite human

condition, to help him attain the final stage of complete

self-consciousness - as part of the history of creation.Using

the dialectical method (the step by step evolution of a thought or idea

through the struggle of contradicting propositions in the quest of a

higher level of truth), Hegel outlined how this occurred.

Through this progressive process, God and man (the Absolute and the

Finite) are two juxtaposed players joined in a dialectical process of

reaching toward each other in a process of self-realization. This

process moves both sides to ever higher levels of realization. In

this God is as dependent on man as man is dependent on God for their

mutual realization.This

same dialectical process worked also for whole societies. In his

1821 Philosophy of Right, Hegel was trying to demonstrate through his

dialectical method the path to a just political/social order. On

the one hand society consisted of laws which were necessary for

the good ordering of life. But man also possessed a free

conscience and the obligation to exercise this conscience as part of

his dignity. It was in the struggle to balance the need for a

legal order and a realm of responsible personal freedom that the just

society emerged. The

dangers were always the emergence of not a synthesis between these two

tendencies, but the victory of one tendency over the other: a

legal tyranny or an anarchy of human wilfullness. For Hegel the

closest model for an ideal state was the family and the medieval guild

– there being no such just realm known to him at that time within the

larger political world. His hope was that the urge to justice

would ultimately produce the birth of such a higher political

state.By

the time of his publication of the Philosophy of Right his reputation

was well established in Germany – if not also in all of Europe. A

seat in his lectures was a prized possession for any

student. Careful notes were taken of his lecture s – which

was where his work now was wholly contained. His

interest in the wider realm of philosophy, art, religion, science also

broadened during this time. But overall his work remained the

same: to demonstrate that history was a working out of the will

of God through an ever-heightening human consciousness. Man was

moving into an era of careful human thought – motivated by a deep

devotion to God. The end product for Hegel was indeed the

outworking of the Kingdom of Heaven here on earth ... as the fulfilment

of the promise that Jesus had made so long agoHegel’s

legacy.

German scholarship (indeed much of all European scholarship) after

Hegel was fairly single-minded in this quest of an all-determining

transcendent world Spirit. Things were studied in order to draw

out the hidden pattern of this Spirit – so as to enable man to work in

cooperation with such divine destiny. This

was a powerful idea, forming the underpinning of the revolutionary zeal

of the young reformers of Germany, the "Young Hegelians," who

interpreted Hegel's philosophy as a mandate to work with and for the

World Spirit in bringing about a heightened or evolved cultural

development.This

revolutionary attitude even became part of the Scientific Socialism of

Karl Marx. Marx's philosophy, though its Materialist foundations

were diametrically opposed to Hegel's Idealism, was strongly influenced

by Hegel's idea of a transcending principle moving through

history. In the hands of Marx, this principle directed the

revolutionary course of human life, especially in the stage by stage

development of the economic class-base of society.Inspirer of the rising nationalist spirit in

Germany.

Hegelianism also touched on group pride, as nations or classes

came to see themselves as being under the special anointing of the

world Spirit to take the lead to direct history into the next

era. This fed powerfully into German nationalism, with its sense

of special German historical destiny. This also fed powerfully

into the working class movement which came to view the workers of the

world as the true moral underpinning of the world to come.

Hegel's

major works or writings: Hegel's

major works or writings:

The Phenomenology

of Mind (or Spirit) (1807)

The Objective Logic

(1812-13)

The Subjective Logic

(1816)

Encyclopedia of the

Philosophical Sciencies (1817,

republished and expanded many times thereafter)

Science of Logic

Philosophy of Spirit

Philosophy of Nature

Philosophy of Right(1821)

Philosophy of Religion

(1832)

History of Philosophy

(1833-36)

Philosophy of Fine

Art (1835-38)

Philosophy of History

(1837)

Friedrich

Schelling (1775-1854) Friedrich

Schelling (1775-1854)

Schelling's

major works or writings: Schelling's

major works or writings:

System of

Transcendental Idealism (1800)

Heinrich

von Treitschke (1834-1896) Heinrich

von Treitschke (1834-1896)

Von Treitschke was a professor

of history and politics in a number of German universities: Leipzig, Freiburg,

Kiel, Heidelberg and Berlin. He was an ardent German nationalist

who glorified war as the process by which the spirit of a people works

itself forward in unity and strength. He looked to the German State,

headed by the autocratic Prussian King, as the leading instrument for the

outworking of the German national will.

He was a member of the German

Reichstag (the popular Assembly) 1871-1884.

von

Treitschke's major works or writings: von

Treitschke's major works or writings:

History of

Germany in the Nineteenth Century (7

vols)

Wilhelm

Dilthey (1833-1911) Wilhelm

Dilthey (1833-1911)

German neo-Hegelian philosopher

Dilthey's

major works or writings: Dilthey's

major works or writings:

Introduction

to the Human Sciences

Thomas

Hill Green (1836-1882)

Oxford Idealist

Green's

major works or writings: Green's

major works or writings:

Lectures on

the Principles of Political Obligation

Josiah

Royce (1855-1916)

American Idealist |

|

Jean-Baptiste

de Lamarck (1744-1829)

Lamarck took the logic of selective

breeding of animals and hybridization of plants practiced by "enlightened"

European farmers – and surmised that in the long-term this process of passing

on a species' particular strengths to new generations would produce evolutionary

development within the species – and ultimately the creation of new species

themselves.

Lamarck's

major works or writings: Lamarck's

major works or writings:

Zoological

Philosophy (1809)

Charles

Lyell (1797-1875)

He believed that natural

(not divine) forces and processes went into shaping the various features

of the earth (mountains, valleys, islands, deserts, etc.). He studied

these features directly, climbing, digging, exploring – to observe such

things as the impact of erosion, the action of volcanos. From these

observations he deduced various processes by which mountains were built

up by convulsions in the earth's surface, valleys were cut through the

land, and plains were fashioned from eroded hills and mountains.

He viewed the earth as a

living organism, in a constant state of growth and decay, birth and death.

He extended this vision to the inhabitants of the earth – plants and animals – and

saw such dynamics (growth and decline, birth and death) typical not just

of individuals but of whole species of biological life – of whole families

of plants and animals.

He also estimated that the

earth was possibly millions of years old.

Lyell's

major works or writings: Lyell's

major works or writings:

Principles

of Geology (1830-33)

The Geological Evidences

of the Antiquity of Man (1863)

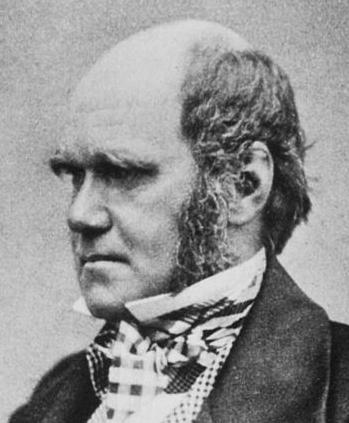

Charles

Darwin (1809-1882)

There is no question that the

greatest impact on 19th century thought came from Charles Darwin.

Darwin was a naturalist, a "fact" gatherer, who not only contributed to

our understanding many new details about natural life – but also developed

a hypothesis about why nature seemed to take the shape she did. His

facts seemed to point to the evolution of all living species through a

process of competition for survival which led, by accidental causes, to

"natural selection" or "survival of the fittest." The impact of his

hypothesis on the Western intellect cannot be overestimated – for his theory

still underpins most modern thinking about life today!

But note: Darwin did not

invent the idea of evolution – for it had been a very big element of Western

thought since the on-set of the Enlightenment. The French Revolution

for instance was quite certain that it was about not only social justice,

but also progressive development – growth of human society and the human

intellect.  Darwin's

major works or writings: Darwin's

major works or writings:

The Origin

of the Species (1859)

The Descent of Man

(1871)

The Voyage of the

Beagle

Herbert

Spencer (1820-1903)

Darwinism

was further buttressed by the writings of other social philosophers of

the day, including notably Herbert Spencer ... who had been moving in

the direction of Darwin’s thinking even before Darwin published his

first work in 1859. Spencer had been working on both social

theory (his 1851 Social Statistics) and personal development theory (his 1855 Principles of Psychology)

... his work heavily influenced not only by Malthus but also by the

theories of Lamarck. Then when Darwin’s work was published in

1859 Spencer came out full force in his support of evolution as the

basic doctrine of life ... in every aspect of life on earth. Soon

Spencer would even outdistance Darwin as the most recognized

philosopher of the late 1800s. But the very names ‘Darwin’ and

‘Darwinism’ would still serve as the most powerful symbols able to

raise strong debate, pro and con ... not only well into the 20th

century but still even today..  Spencer's

major works or writings: Spencer's

major works or writings:

Social Statics

(1850)

Principles of Biology

(1864)

T.

H. Huxley (1825-1895)

T.H. (Thomas Henry) Huxley was

a major developer of the the "agnostic" position with respect to the existence

of God, seeing only "natural" processes in the evolution of biological

life.

Huxley's

major works or writings: Huxley's

major works or writings:

Man's Place

In Nature (1863)

Practical Biology

(1875)

Agnosticism (A Reply

to Henry Wace) (1889)

Ethics and Evolution

(Romanes Lecture) (1893) Huxley distances himself from the position

that human morality must mirror the doctrine of "survival of the fittest,"

claiming that there is no serious connection between the violence of biological

or physical evolution over the aeons and the universality of moral principle.

|

|

Gregor

Mendel (1822-1884)

An Augustinian monk/teacher

in Austria. Mendel studied plants, in particular the ordinary pea,

in order to detect the ways in which traits of parents are passed on to

their offspring through principles of heredity. In 1865 he presented

his findings – only to discover that his biological theories ran counter

to the environmental theories of natural selection of the rising group

of Darwinists. It was not until after his death that his theories

came to light again – and eventually he became recognized as the founder

of the science of genetics.

Mendel's

major works or writings: Mendel's

major works or writings:

Treatises

on Plant Hybrids (1865)

Ivan Petrovich

Pavlov (1849-1936)

Pavlov is famous for his explanation

of the "conditioned response," worked out in his experiements (late 1800s)

with dogs – but extended in theory also to human behavior. By associating

the ringing of a bell with the presenting of food to a dog, the dog came

eventually to salivate not just in the presenting of food but eventually,

as a result of "conditioning" even to the sound of the bell in itself – even

without food being present.

|

|

Henri

de Saint-Simon (1760-1825)

Saint-Simon's

major works or writings: Saint-Simon's

major works or writings:

Lettres d'un

habitant de Genève ÃÂ ses contemporains (Letters of

an

Inhabitant of Geneva to His Contemporaries)

(1803)

De la réorganisation

de la société européenne (On the Reorganization

of

European Society)

(1814)

L'industrie

(Industry)

(1816-1818, with Auguste Comte)

Nouveau Christianisme

(The New Christianity)

(1825)

Charles

François-Marie Fourier (1772-1837) Charles

François-Marie Fourier (1772-1837)

Fourier's

major works or writings: Fourier's

major works or writings:

Théorie

des quatre mouvements et des destinées générales

(The Social

Destiny of Man; or, Theory of the Four Movements)

(1808)

Traité

de l'association agricole domestique (Treatise on Domestic Agricultural

Association)

(1822)

Le

Nouveau Monde industriel (The New Industrial World)

(1829-1830)

Ludwig

Feuerbach (1804-1872)

German materialist; claimed

that religion was merely a projection of the human ego to give hope to

human dreams.

Feuerbach's

major works or writings: Feuerbach's

major works or writings:

The Essence

of Christianity (1841)

The Philosophy of

the Future (1843)

The Essence of Religion

(1853)

Pierre-Joseph

Proudhon (1809-1865) Pierre-Joseph

Proudhon (1809-1865)

Karl

Marx (1818-1883)

In typical German fashion, the

sociologist Karl Marx picked up on Hegelian Idealism to project a special

destiny for the European working classes.

But Marx moved more to the

middle ground between Hegel and Darwin in projecting how the working classes

would come to power. Not by accident (as per Darwin) nor by some

unseen spirit (as per Hegel) but through the necessary logic of the forces

of production: the world belonged to those who owned the material forces

of production (factories, mines, etc.). The industrial workers would

inevitably wield the power of their vastly greater numbers, to seize the

forces of production from the liberal entrepreneurs and institute a new

society based on worker values – where all would live voluntarily and communally

(owning no property but sharing everything in common) according to a high

spirit of brotherly love. Thus communism or Marxism was born.

Marx's

major works or writings: Marx's

major works or writings:

Communist

Manifesto (1848)

Capital (Volume I: 1867)

Friedrich

Engels (1820-1895) Friedrich

Engels (1820-1895)

Engels'

major works or writings: Engels'

major works or writings:

Principles

of Communism

The Origin of the

Family, Private Property and the State

Ludwig Feuerbach and

the End of Classical German Philosophy

On the History of Early

Christianity

Anti-Dühring

Sidney

Webb (1859-1947)

Webb's

major works or writings: Webb's

major works or writings:

|

ARCHEOLOGY, CULTURAL HISTORY, ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY |

Jean

François Champollion (1790-1832)

The French archeologist who

translated the Rosetta stone found in Rashid (Rosetta) Egypt (publishing

his work in 1822) – and was thus able to provide a system for translating

ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, which since ancient times had remained

largely a mystery.

On the stone itself was a

priestly decree written around 196 BC – in three parallel scripts:

ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic, Egyptian demotic (language of the common

Egyptian around 196 BC) and Greek (language of the Ptolemaic dynasty ruling

Egypt at that time). By first detecting royal names he was able to

identify a dozen of the hieroglypic symbols – and then slowly begin to work

from there in identifying yet other ancient Egyptian names and titles.

Eventually this opened up understanding to even more of the hieroglypics

until the full hieroglyphic text could be read.

Jakob

Christoph Burckhart (1818-1897)

A Swiss historian who, in his

study of Renaissance Italy, established many of the cannons of modern cultural

history.

Though he was the son of

a Protestant pastor and was sent off to school to become a pastor himself

(though receiving much education in the classics along the way) he eventually

abandoned these plans – and took up the pantheistic vision of life characteristic

of many of the members of the romantic movement.

A love for classic art and

architecture eventually translated itself into a fascination for the Italian

Renaissance, which he studied up close through regular travels to Italy.

Over time he withdrew himself from the political romanticism of his colleagues,

becoming less and less confident that modernism was going to produce

a civilization as high as that of the classic and renaissance past.

His life as a teacher at the University of Basle was quiet and unexceptional.

It was, instead, the publication in 1860 of his study of Renaissance Italy

that brought his name to public notice. This study of Renaissance

art and culture was unparalleled – and long remained (even well into the

20th century) the standard study on the subject.

Burckhart's

major works or writings: Burckhart's

major works or writings:

Die Zeit Konstantins

des Grossen (The Age of Constantine the Great)

(1853)

Die Kultur der Renaissance

in Italien (The Civilization of the Renaissance in

Italy)

(1860)

Griechische Kulturgeschichte

(History of Greek Culture)

(edited posthumously:

1898-1902)

Heinrich

Schliemann (1822-1890)

German archeologist who discovered

the locations of ancient Troy and Mycenae, the main settings for

the ancient Homeric epic, the Iliad.

As a youth he was fascinated

with the Homeric legends and wanted to go to these places to see them for

himself. But he was told that the places were entirely mythical,

the product of ancient imaginations. Nonetheless he remained committed

to his hope.

He proved to be very able

in both languages (he mastered over ten languages) and commerce (he worked

his way up from errand boy to a master speculator in the movement of industrial

and military materials). Once he had established himself in the world

of wealth (he was nearly 50 at that time) he then devoted himself to following

his youthful dream.

In 1871, using Homer's descriptions

of Troy and the area around the ancient city, he decided that the description

fit a hill in northwestern Turkey at Hissarlik. There indeed he uncovered

the ancient city of Troy (though the treasures he brought out as "Priam's

treasures" actually belonged to a Trojan culture many centuries older than

Priam's).

He then in 1874 turned his

attentions to Greece, to Mycenae, the supposed site of the ancient palace

of Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek expeditionary army during the times

of the war with Troy. Here too he uncovered graves and considerable

wealth which he supposed to be Agamemnon's (actually it too belonged to

an older culture).

Overall, he convinced the

world to pay closer attention to ancient mythology – to understand that

though the accounts themselves seemed entirely fantastic by our standards,

nonetheless they were stories that ultimately had their basis in some kind

of "historical fact."

E. B.

Taylor (1832-1917)

E.B. (Edward Burnett) Taylor

was the coiner of the term "animism" (belief in individual souls or anima

in all things, even trees and mountains), which he posited as the

first stage of religious evolution.

Taylor's

major works or writings: Taylor's

major works or writings:

Anahuac

(1861)

Researches into the

Early History of Mankind (1865)

Primitive Culture

(1871)

William

Robertson Smith (1846-1894)

Cultural evolutionist: studied

the historical stages of development of the belief system of a people.

Smith's

major works or writings: Smith's

major works or writings:

Lectures on

the Religion of the Semites (1889)

Arthur

Evans (1850-1941)

English excavator of the ancient

bronze age culture of Crete – which he named "Minoan" after the ancient

myth about King Minos of Crete and his fabulous bull held deep within the

labyrinth of his underground palace. At Knossos, the ancient capital of

this culture, Evans reconstructed the palace to look closely like the original.

Purists later would criticize his tampering with the archeological evidence

with his reconstructions. But at the time this was quite a novel

approach to archeology – and was viewed as quite helpful in bringing the

past to life again.

Flinders

Petrie (1853-1942)

English archeologist – considered

the "father" of modern Egyptology. His focus was on gathering information

about the past, not its material riches or treasures, or even museum-worthy

show items (which had been pretty much the goal of archeology until his

time).

He began as a surveyor of

the pyramids and then progressed to excavator – working to uncover various

layers of ancient Egyptian history. He kept careful records of all

his diggings, and considered all finds, no matter how small, to be of important

historical significance. He developed a system of typologies for

pottery, arranging them according to the time periods in which they typically

appeared across the ancient Egyptian cultural landscape, which could then

help to identify the different historical layers as they were exposed in

his diggings.

ÃÂmile

Durkheim (1858-1917)

Durkheim was the first Chair

of Sociology, at the Sorbonne in Paris. Indeed, he is considered

the father of modern sociology.

He studied societies not

from the point of view of their relative development in comparison with

other societies – but from the point of view of their own functionality:

how well they worked as societies. In particular, he was interested

in how each society, through the working of its various social "organs,"

met the tasks of socializing its own members. His approach laid out

the groundwork for the functionalist school of sociology or anthropology.

Durkheim put forth the view

that individual humans are strongly influenced by the collective conscience

of the society they grow up in. This collective conscience is more

than merely the sum of all the individual members making up society – but

has its own existence which provides continuity and cohesiveness for society.

Suicide results when individual members are not able to integrate successfully

with that collective conscience – when they suffer "anomie."

Durkheim's

major works or writings: Durkheim's

major works or writings:

De la division

du travail social (The Division of Labor)

(1893)

Les règles

de la méthode sociologique (Rules of Sociological Method)

(1895)

Le suicide (Suicide:

A Study in Sociology)

(1897)

Pragmatism and Sociology)

(1914)

Les formes élémentaires

de la vie religieuse (Elementary Forms of Religious

Life)

(1915)

Max

Weber (1864-1920) Max

Weber (1864-1920)

Weber's

major works or writings: Weber's

major works or writings:

The Protestant

Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

|

THEOSOPHY AND RELIGIOUS SYNCRETISM |

Helena

Petrova Blavatsky (1831-1891) Helena

Petrova Blavatsky (1831-1891)

Blavatsky's

major works or writings: Blavatsky's

major works or writings:

Isis Unveiled:

A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science

and Theology. (2 vols -1877)

The Secret Doctrine:

The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy.

(2 vols -1888)

The Key to Theosophy

(1889)

|

|

Søren

Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

Though Kierkegaard was most

definitely a 19th century individual, his work and legacy had to wait well

into the twentieth century until it had its great impact within philosophical

circles.

Kierkegaard's

major works or writings: Kierkegaard's

major works or writings:

Enten – Eller (Either/Or) 2 Vols - 1843

|

CHRISTIANITY ON THE

DEFENSIVE |

PART ONE:

CATHOLIC/ANGLICAN CONSERVATISM

Joseph

de Maistre (1754-1821)

ultramontanist

de

Maistre's major works or writings: de

Maistre's major works or writings:

Essai sur

le principe generateur des constitutions politiques et de autres

institiutions

humaines (Essay Concerning the General Principle of Political

Constitutions

and of Other Human Institutions) (1803-1817)

Lettres sur l'Inquisition

(1815)

Du pape (On

the Pope)

(1819)

Les Soirees de Saint-Petersbourg

(Evening

Parties of Saint Petersburg)

(1821)

Cardinal

John Henry Newman (1801-1890)

Co-founder (with Richard Hurrell

Froude and John Keble) of the Oxford Movement and publisher of Tracts

for the Times (1833 and after). But he came to question the true

catholicity of the Church of England (announced in Tract 90) and converted

to Catholicism in 1845. He became cardinal in 1879

Newman's

major works or writings: Newman's

major works or writings:

Apologia pro

Vita Sua (autobiography) (1864)

Tracts for the Times,

No. 1

Tracts for the Times,

No. 2

Tracts for the Times,

No. 3

Tract Ninety

(1841)

Essay on the Development

of Christian Doctrine (1845)

Edward

Bouverie Pusey (1800-1882)

Pusey took over leadership of

the Anglo-Catholic movement (in 1845 after Newman's defection). He claimed

that the movement involved the restoration of true "primitive Christianity."

Henry

Edward Manning (1808-1892)

Converted to Catholicism in

1851; an extreme ultra-montanist; became cardinal in 1875

Pope

Pius IX (pope: 1846-1878)

Giovanni

Maria Mastai Ferretti (1792-1878) ... the longest reigning pope.

Pius started out as a very Liberal pope, pardoning and freeing

political prisoners in his first year as pope. But he soon found

himself strongly opposed to the Revolutions of 1848, which shook all of

Western Europe deeply. Pressure was on him to join the effort led

by Albert of Sardinia to force the Austrians out of northern

Italy. But Pius did not want to get involved in any

war. This decision undercut deeply his popularity at a time

of rising nationalism among the Italians.

Then calls were made

for his to reform the operation of the Papal States themselves

(still quite extensive in size in middle and northeastern Italy) ...

something that Liberals had long been demanding. His hesitancy

merely undercut further his national popularity.

Finally, he was forced

to grant a constitution for a two-chamber parliament to assist him

govern the Papal States. Little by little he was losing the

reputation among the Italians.

Briefly Rome was taken

over by revolutionaries who attempted to convert the Papal States into

a Roman Republic ... in the hopes that this would be the first step in

the establishment of a fully national Italian state. But French

troops were sent to Italy and quickly shut down the new republic. And

thus the Papal States were returned to papal governance.

The Papal States would

remain as such until 1860 ... when Victor Emmanuel II of the rising

Sardinian kingdom was able to bring under his royal control all of the

Papal States - except Rome and Rome’s surrounding Latium region - in

his effort to create a unified Kingdom of Italy. Then in 1870, as

a result of a plebiscite held on the issue, a huge majority voted that

even that remaining portion would be taken from the papacy and included

as part of the Kingdom of Italy. From that point on, Pius

considered himself a “prisoner of the Vatican.”

Pius never would

recognize the right of the Italian kingdom to exist ... and

excommunicated its leaders, including King Victor Emmanuel.

Indeed, the papacy would continue to refuse recognition of the Kingdom

of Italy ... all the way up until 1929 - when Mussolini and Pope Pius

XI signed the Lateran Treaty, the papacy receiving reparations payments

for the loss of its territory to the Italian state ... and the

recognition of Vatican City as an independent mini-state within the

city of Rome. (a fifth of a mile or half of a kilometer squared in

size).

Notable during his

reign was the declaration of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception

(1854), the Syllabus of Errors (1864), and the gathering of the First

Vatican Council (1869-1870) in which the doctrine of papal

infallibility was declared.

Pius

IX's major works or writings: Pius

IX's major works or writings:

Ineffabilis

Deus (1854) [the immaculate conception of the virgin]

Syllabus of Errors(1864)

Vatican I

(1869-1870)

Papal infallibility

(1870)

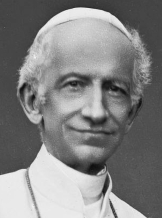

Pope Leo

XIII (pope 1878-1903)

Giaocchino

Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci (1810-1903). He was born of a noble

Italian family (and his older brother Giuseppe also a prominent

Catholic official), Jesuit trained, and early on a vital part of the

Vatican’s diplomatic service. As pope, he no longer had the

responsibilities of the Papal States to concern him. But instead

he turned his political thoughts to matters of social justice for the

common worker and family. He was opposed to both Socialism and

unregulated Capitalism ... supporting both trade union rights and

personal property rights. And he was an excellent diplomat,

bringing the Catholic church back into the graces of surrounding

European powers. Italy, however, remaining as a papal problem ...

especially as to papal appointment to certain church positions ... as

the Austrian emperor and now the Italian monarchy felt that this was

its right to do so.

Leo also continued to follow the theological direction set out by his

predecessor, Pius IX ... affirming Mary as “mediatrix” in the

relationship between the believer and Jesus. He also stressed the

importance (by way of eleven encyclicals he issued!) of the Rosary ...

a prayer employing rosary beads to help keep correct count of the ten

elements of the prayer ... or ten “Hail Marys.” And he too

stressed the importance to the Church of the Thomast legacy.

He also stressed the importance of reviving the theology of Thomas

Aquinas ... to the point of making it the official theological

foundation of the Catholic Church. Giaocchino

Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci (1810-1903). He was born of a noble

Italian family (and his older brother Giuseppe also a prominent

Catholic official), Jesuit trained, and early on a vital part of the

Vatican’s diplomatic service. As pope, he no longer had the

responsibilities of the Papal States to concern him. But instead

he turned his political thoughts to matters of social justice for the

common worker and family. He was opposed to both Socialism and

unregulated Capitalism ... supporting both trade union rights and

personal property rights. And he was an excellent diplomat,

bringing the Catholic church back into the graces of surrounding

European powers. Italy, however, remaining as a papal problem ...

especially as to papal appointment to certain church positions ... as

the Austrian emperor and now the Italian monarchy felt that this was

its right to do so.

Leo also continued to follow the theological direction set out by his

predecessor, Pius IX ... affirming Mary as “mediatrix” in the

relationship between the believer and Jesus. He also stressed the

importance (by way of eleven encyclicals he issued!) of the Rosary ...

a prayer employing rosary beads to help keep correct count of the ten

elements of the prayer ... or ten “Hail Marys.” And he too

stressed the importance to the Church of the Thomast legacy.

He also stressed the importance of reviving the theology of Thomas

Aquinas ... to the point of making it the official theological

foundation of the Catholic Church.

Leo

XIII's major works or writings: Leo

XIII's major works or writings:

Encyclical (1891)

[Mary as the mediator between the Christian and Christ]

|

|

PART TWO:

PROTESTANT LIBERALISM AND BIBLICAL CRITICISM

Friedrich

Schleiermacher (1768-1834)

In his early years he stressed

the importance of faith as being the inner work of the spirit of Christ – a

spirit which when formalized into the fixed dimensions of scripture was

crippled. However, his Leben Jesu (published posthumously in 1864)

attempted to distill the essential or "historical" Jesus from the Scriptural

record – resulting in itself a formalized (Liberal) picture of Jesus.

Schleiermacher's

major works or writings: Schleiermacher's

major works or writings:

Reden über

die Religion (Religion: Speeches

to Its Cultured Despisers) 1799

The Christian Faith

(1821-22)

Leben Jesu

(1864)

Ferdinand

Christian Bauer (1792-1860)

German Idealist. Used

the Hegelian dialectic to describe the development of 1st century theology

and writings (the NT): 1) the Jewish Christian "thesis" confronts

2) a Gentile or pagan Christian "antithesis" to 3) produce a second-generation

Catholic Christian "synthesis." He concluded (wrongly) that this

permitted him to date NT writings according to where they fit into this

"development."

Bauer's

major works or writings: Bauer's

major works or writings:

Paulus der

Apostel Jesu Christi (1845)

David

Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874)

Strauss took Schleiermacher's

quest for the historical Jesus forward – employing rationalistic criteria

for distilling such a Jesus from the agendas of the first- century Church;

the result was a largely secular-liberal image of Jesus as the wise teacher

Strauss'

major works or writings: Strauss'

major works or writings:

Leben Jesu

(1835-1836)

Albrecht

B. Ritschl (1822-1889)

Ritschl's

major works or writings: Ritschl's

major works or writings:

The Christian

Doctrine of Justification and Reconciliation (3 vols.: 1870-1874)

History of Pietism

(3 vols.: 1880-1886) [a disapproving account of pietism]

Ernst

Renan (1823-92)

Renan's

major works or writings: Renan's

major works or writings:

La vie de

Jesus (1863)

Julius

Wellhausen

Wellhausen's

major works or writings: Wellhausen's

major works or writings:

Die Composition

des Hexateuchs (1885; from essays: 1876-1877) In this work, he

carried forward the work of Jean Astruc (previous century) in clearly laying

out the evidence of multiple authorship of the 1st six books of the Jewish

Scriptures or Old Testament: the "documentary hypothesis."

Israelitische und

Jüdische Geschichte In this work, he posited the religious

development of Israel (in a Hegelian evolution) from primitive Yahwism

of the people, through a refinement by the prophets, to a codification

by post-exilic priests of a monotheistic system. Also, the Psalms

and wisdom literature he dated from post-exilic times – possibly even the

Maccabean period.

Adolph

von Harnack (1851-1930)

von

Harnack's major works or writings: von

Harnack's major works or writings:

Das Wesen

des Christentums (1899-1900) In this work he removed the

eschatological aspects of the coming Kingdom – at least from the Last Days

with its awful judgment of angels and demons, of principalities and powers – to

an already-present spiritual rule of God within the human soul – focusing

the kingdom on the present (not future) possibilities offered in this earthly

existence.

History of Dogma

(3 vols.: 1886-1889)

What is Christianity?

(from lectures: 1899-1900)

Charles

A. Briggs (1841-1913)

A Union Seminary Professor who

in 1893 was dismissed from the Presbyterian ministry as a result of a heresy

trial relating to his biblical scholarship.

Hermann

Gunkel (1862-1932)

He looked beyond the literary

structure of Scripture itself to the contemporary cultural milieu of the

times in which they were composed – discovering that though the texts may

show a late editing, they reflect cultural practices of much greater antiquity,

evidence that the material is much older than merely the last editing.

Also, he discovered different literary forms or genres which arose out

of different social contexts (Sitz im Leben) – which were formalized over

time into very precise literary formulae. Many of these same forms are

found in the literature of surrounding cultures – giving us an ability to

date their origins more precisely.

Gunkel's

major works or writings: Gunkel's

major works or writings:

Schöpfung

and Chaos in Urzeit and Endzeit (1895)

Genesis übersetzt

und erklärt (1901)

Wilhelm

Bousset

Jewish apocalyptic was not a

monolithic affair in Christ's times – but was widely variant; Jesus felt

that the coming of the Kingdom (which was immanent) was not of the order

of the particular horror which John the Baptist preached – because of the

very manner in which Jesus delighted in the things of the present age and

the possibilities of harmonious life now among the people; reportings of

Jesus' words to the contrary were so out of character with him that they

more likely reflect the viewpoint of the first century church than Christ

himself.

Bousset's

major works or writings: Bousset's

major works or writings:

Jesu Predigt

in ihrem Gegensatz zum Judentum (1892)

Wilhelm

Wrede

Claimed that Jesus became "Messiah"

only in the minds of his disciples after his death.

Alfred

Loisy (1857-1940)

Historical criticism and form

criticism seem to imply that Christianity was really only just one of many

competing mystery religions of its times: Jesus who died on the cross was

only another Adonis or Osiris who, having suffered a violent death, returned

to life – to incorporate his mystical devotees into the saving work (immortality

or life eternal) of his own resurrection; indeed, the Christ of Christianity

is essentially the work of the early church. No understanding of the "historical"

Jesus can be drawn from Scripture – as Jesus is lost within the eyewitness

of his early followers.

|

|

PART THREE:

PROTESTANT CONSERVATISM

Archibald