4. THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC

CHRISTIAN FOUNDATIONS

| CONTENTS

The strong Chrisitan component in the discussions The strong Chrisitan component in the discussions

Ben Franklin's reminder Ben Franklin's reminder

The Framer's Christian take on the issue The Framer's Christian take on the issue

Comparing the American and French efforts at Republic-building Comparing the American and French efforts at Republic-building

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 146-156.

|

THE STRONG CHRISTIAN COMPONENT

IN THE DISCUSSIONS |

|

The example also of Ancient Israel

These men were also aware of

another example of an ancient people who had tried to be self-ruling,

similar to what the Americans were trying to do. These constitutional

Framers were quite well read up on the Bible and were very aware of the

sad record of the ancient Israelites in their efforts to stay a strong,

yet free people. Indeed, as Christians, the Framers were very well

aware that human sin (pride, jealousy, lust for power, etc.) stood as a

constant threat to any effort to empower a central authority.

For generations, God alone was ancient Israel's

sovereign. The Israelites had called on him time and again to protect

and preserve them against their enemies – foreign and domestic. But

their loyalties to God were most unsteady. Finally at one point, the

people called out to their spiritual leader Samuel, "Give us a king."

They felt that they could be more successful as a people if they were

more like the other nations around them, ruled not by some invisible

God but by a very visible, very politically impressive king. But

through the counsel of Samuel, Israel was warned by God himself that

their effort to have a government like other nations would be their

downfall. But they wanted a king to rule over them nonetheless. And so

God gave them a king. But as Samuel had predicted, in this move away

from God the Israelites soon fell under the political tyranny of their

kings. The kings took away the Israelites' liberties and amassed

considerable wealth and power of their own at the expense of the

people. For generations, God alone was ancient Israel's

sovereign. The Israelites had called on him time and again to protect

and preserve them against their enemies – foreign and domestic. But

their loyalties to God were most unsteady. Finally at one point, the

people called out to their spiritual leader Samuel, "Give us a king."

They felt that they could be more successful as a people if they were

more like the other nations around them, ruled not by some invisible

God but by a very visible, very politically impressive king. But

through the counsel of Samuel, Israel was warned by God himself that

their effort to have a government like other nations would be their

downfall. But they wanted a king to rule over them nonetheless. And so

God gave them a king. But as Samuel had predicted, in this move away

from God the Israelites soon fell under the political tyranny of their

kings. The kings took away the Israelites' liberties and amassed

considerable wealth and power of their own at the expense of the

people.

The Protestant component

This was exactly

what the American colonists had felt had come to pass with the English

kings. The English kings had

tried to take the place in the life of the nation that belonged only to

God. This effort of the kings to play God, claiming Divine Rights to do

so, was what had finally prompted their revolt, their War of

Independence. All Americans, as Protestant Calvinists (New England

Congregationalists, Reformed Dutch, Middle Colonies Presbyterians,

etc.), Baptists, Quakers and even as Church of England vestrymen, well

understood that they too had Divine Rights which no king had the right

to disregard or trample on.

Indeed, in one form or another nearly all of those

who assembled to draft this new venture into republican government were

Christians, Protestant Christians. They were politically informed by

their own sense of the longer history of the Church. Protestantism was

very aware of the fact that prior to the adoption of Christianity by

the Roman emperors in the 300s, Christianity had been a free religion,

under no central political control, but self-governing by small

communities of believers themselves in accordance with their strongly

Christian moral consciences and ingrained spiritual beliefs. The

Christians of the first three centuries of the Church had survived

terrible persecution from the Roman political authorities and yet not

only had kept themselves together as a people but had grown rapidly at

the same time. Pure Christianity needed no hierarchical authority to

organize and direct the faith of the true believer.

But with the conversion of Roman Emperor

Constantine to Christianity in the early 300s, Christianity had become

Romanized, that is brought under the political organization and

protection of the Roman political hierarchy. From the Protestant point

of view, this was a horrible step backward for the Christian faith, for

this development made the faith henceforth a matter more of the

political interests of the politically powerful than that of the

personal faith of the individual believer. Protestantism was fiercely

sensitive on this subject. But with the conversion of Roman Emperor

Constantine to Christianity in the early 300s, Christianity had become

Romanized, that is brought under the political organization and

protection of the Roman political hierarchy. From the Protestant point

of view, this was a horrible step backward for the Christian faith, for

this development made the faith henceforth a matter more of the

political interests of the politically powerful than that of the

personal faith of the individual believer. Protestantism was fiercely

sensitive on this subject.

Thus the Framers tended to be strongly

anti-hierarchical in both their religion and their politics. The

Puritan-Protestant predecessors of the Framers had lived in terror of

the forced Catholicizing of England which the Catholic powers of Europe

(principally their perpetual enemies Spain and France) sought to

promote. The sending of the Spanish Armada to England in 1588 was

loudly justified by Spanish King Philip II as a result of God's command

to him as Defender of the Faith to bring the English back to the True

Faith (Catholicism) – by force if necessary.

Philip II

The humiliating defeat of Philip's mighty naval

Armada therefore ranked not only as a victory for English independence

but also as victory in the defense of their Protestant faith. This

conflict with the Spanish consequently left an even deeper dislike of

hierarchical Catholicism among Protestant Englishmen. In part, the

Glorious Revolution in England a century later was prompted by the

evidence that English King James II was secretly Catholic in loyalties

and planning an alliance with Catholic France to crush the power of the

highly Protestant English Whigs who controlled Parliament.

James II

James II

Protestantism as political culture

Thus

the Protestant faith of the English colonists was a matter of great

political, economic and social importance to them. Their personal

freedom and their religious faith were to them inseparable items. As

Protestants they chose their own pastors, elected their own elders and

deacons to manage their local congregations, read and interpreted their

Bible readings on their own – without a priest performing that function

for them – and came to their own opinions on theological matters

themselves as a matter of their basic rights. This was a matter of

great personal distinction to them.

Indeed, not only was the idea of having their

lands to the West put under Catholic hierarchical authority that

reached to Rome – but also the idea (which was being discussed openly

by King George III) of putting the English colonies under the authority

of the Anglican bishops (which the king himself personally supervised)

had been one of the underlying reasons they finally declared their

independence from the English king in 1776. Indeed, not only was the idea of having their

lands to the West put under Catholic hierarchical authority that

reached to Rome – but also the idea (which was being discussed openly

by King George III) of putting the English colonies under the authority

of the Anglican bishops (which the king himself personally supervised)

had been one of the underlying reasons they finally declared their

independence from the English king in 1776.

Their Protestant faith registered itself not only

in terms of the things they opposed (namely, hierarchically-controlled

religion) but the things they aspired to. Their republican instincts

were shaped strongly by the way their churches operated. Their church

officers were elected by the congregation on a regular basis and, at

least on the part of the very strong Presbyterian component among them,

they even developed regional representative government in the form of

their Synods (Senates) attended by pastoral and lay representatives.

Ultimately, community life, both religious and civil – by long

established habit – was to their understanding always governed from the

ground up, not the top down. They strongly conceived of government as

being collegial rather than hierarchical. Generations of them had lived

and died for this principle. They would have it no other way.

|

|

God as the guarantor of the success of America's new Republic

Indeed, the constitutional Framers who gathered at Philadelphia in 1787

saw themselves and their challenge very much operating within the

context of God's will. They were very well aware that God Almighty,

which in the fashion of the times they often referred to as

"Providence" as in "The One Who Provides," was the one empowerment that

had enabled them recently to succeed in their very risky revolt. Apart

from the direct – and frequent – assistance from God, it would have

been highly unlikely that a handful of mere commoners could have ever

succeeded on their own in a revolt against a powerful king and his

army.

They knew well, and testified often to the fact,

that only God had made the success of the American revolt possible.

They all understood that it was not the size of the American army, nor

the cleverness of their generals – but it was the hand of God operating

among them that had brought them successfully through these trying

times.

Ben Franklin's reminder

At one point in

late June of 1787, during the heated debates in Philadelphia over what

kind of government they had been commissioned to create, Ben Franklin

arose to address the assembly, with a proposal that seemed amazingly

out of character for this great champion of earthly wisdom – namely,

that the group should start each of its daily deliberations in prayer: At one point in

late June of 1787, during the heated debates in Philadelphia over what

kind of government they had been commissioned to create, Ben Franklin

arose to address the assembly, with a proposal that seemed amazingly

out of character for this great champion of earthly wisdom – namely,

that the group should start each of its daily deliberations in prayer:

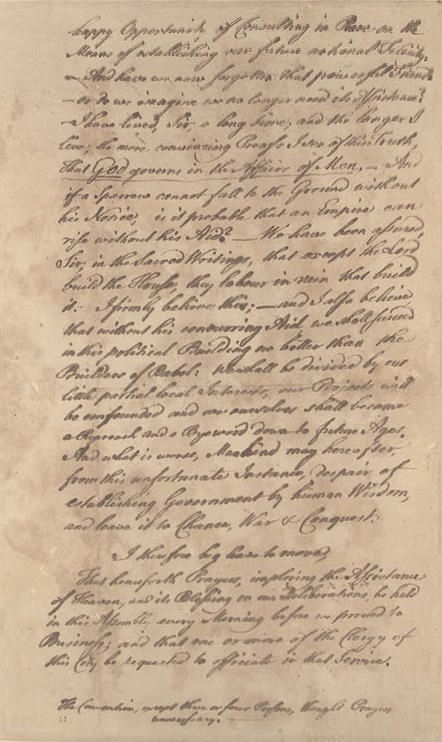

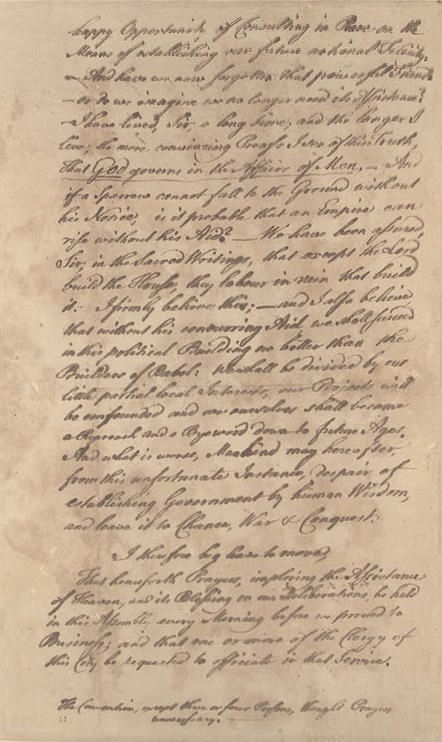

Mr. President

The small progress we have made after 4 or five

weeks close attendance & continual reasonings with each other, our

different sentiments on almost every question, several of the last

producing as many noes and ays, is methinks a melancholy proof of the

imperfection of the Human Understanding.

We indeed seem to feel our own want of

political wisdom, some we have been running about in search of it. We

have gone back to ancient history for models of Government, and

examined the different forms of those Republics which having been

formed with the seeds of their own dissolution now no longer exist. And

we have viewed Modern States all round Europe, but find none of their

Constitutions suitable to our circumstances.

In this situation of this Assembly, groping as

it were in the dark to find political truth, and scarce able to

distinguish it when presented to us, how has it happened, Sir, that we

have not hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of

lights to illuminate our understandings?

In the beginning of the Contest with G.

Britain, when we were sensible of danger we had daily prayer in this

room for the divine protection. Our prayers, Sir, were heard, and they

were graciously answered. All of us who were engaged in the struggle

must have observed frequent instances of a Superintending providence in

our favor. To that kind providence we owe this happy opportunity of

consulting in peace on the means of establishing our future national

felicity. And have we now forgotten that powerful friend?

I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer

I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth that God governs

in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground

without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his

aid?

We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred

writings, that except the Lord build the House they labour in vain that

build it. I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his

concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better

than the Builders of Babel: We shall be divided by our little partial

local interests; our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves

shall become a reproach and bye word down to future ages. And what is

worse, mankind may hereafter from this unfortunate instance, despair of

establishing Governments by Human Wisdom and leave it to chance, war

and conquest.

I therefore beg leave to move, that henceforth

prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our

deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed

to business, and that one or more of the Clergy of the City be

requested to officiate in that service.

page 2 of Franklin's call for prayer

And thus Franklin, the widely respected voice of

American pragmatic wisdom, summed up the situation that faced the

designers of America's new political system.

Madison, who recorded the events of the Convention

(including Franklin's speech), noted that the motion was seconded by

Roger Sherman, but met by a concern (voiced by Alexander Hamilton) that

in taking up this policy at this late date in the process, people would

interpret this resolution as merely the result of the embarrassments

and dissentions among the delegates (which was indeed the case).

Randolph of Virginia then came to the support of the Franklin proposal

with a motion of his own specifying how this resolution was to be

enacted. But the business of the day ended without any vote on

Randolph's motion.

We cannot state that the Constitutional Convention

at this point then turned itself into a gathering of some kind of

saintly religious synod. But clearly all present understood the

significance of what Franklin had just brought to their attention. In

the end what would guarantee the wisdom and durability of this

constitutional enterprise rested ultimately not on the flawed and

contentious wisdom of man, but instead on the mercies of the God that

Provides for his people, especially in guiding their thoughts and

actions.

Furthermore, the matter at hand was not just one

of providing the thirteen states with some kind of political formula

for cooperation, but was (as it had always been) that of building a

test society, a demonstration model founded specially to give hope to

all mankind that a people's government was not only possible, but was

also able to stand strong against forces that would like to return the

little people, the commoners of the earth, back under the domination of

the high and mighty. Thus there could be no failure in this important

enterprise.

Franklin

Benjamin Franklin was a very complex individual, witty, even a bit of a

showman, a journalist and publisher, a scientist and inventor, a

skilled politician and diplomat, and a philosopher possessed of a folk

wisdom that cut through folly and conceit in order to bring authentic

understanding of life to light. He was a strong Christian, but never

dogmatic in his beliefs so that one could therefore identify him with

this or that particular religious group. Some identified him as a

Deist, who believed merely in some kind of Creator-God that simply

observed life from above – and that perhaps (maybe) controlled the

gates of Heaven, opening or closing them to a person at death depending

on that person's moral performance while on earth. But actually

Franklin's Christian faith varied widely over the course of his life,

from a very early negative reaction to the strict Puritanism of his

parents, to indeed something that looked like regular Deism, to an

interest in the power of passionate Christian revival to alter a

person's course in life, to an understanding that indeed God is very

active in the course of life for both individuals and societies. But in

any case, he was a very independent thinker on all subjects near and

dear to him (which were vast in scope). Certainly it was easy to

believe that he mostly was just a secular scientist focused primarily

in studying the mechanics of life (especially this matter of

electricity). Yet others could see in him a person seriously concerned

about the religious matters that were important to all Christians (or

Jews), but in such a way that Christians, ranging from Roman Catholics

to Quakers, could easily believe that he was definitely one of their

particular faith. The man was brilliant, a Humanist in the very best

sense of the word, not really a lofty or isolated Idealist but very

much the intensely involved Realist, and a person able to touch the

hearts of others in a way that truly stood him out as one of the Greats

of the Age.

He was born in Boston in 1706, the last male of

seventeen children born to his father and his two subsequent wives,

given formal schooling only until age ten, supposing himself headed to

the ministry. But at age twelve he took an apprenticeship in a printing

business run by an older brother, James. But at seventeen, Benjamin

broke from that relationship (an illegal act at the time) and escaped

to Philadelphia to work in printing shops there, before heading off to

London to do the same. A couple of years later he returned to

Philadelphia, where he not only resumed his work in the publishing

business but formed a discussion group (English coffeehouse style) of

young members that combined their libraries and engaged in far-ranging

discussions of social interest. Young Franklin was very interested in

public matters, and soon started up a series of newspapers that offered

commentary on the world around him, especially on the matter of what

brought societies to virtue and thus happiness, a theme that would

remain central to Franklin for the rest of his life.

In 1730 he took up a common-law relationship with

Deborah Read, whom he was not allowed to marry because she was already

married to a man that ran off with her money, never to be heard from

again. Franklin brought into that relationship a son, William, born to

him earlier by possibly another woman (or perhaps by Deborah herself?)

and a surviving daughter, who would accompany and look after her father

after her mother died. He and Deborah remained together until her death

in 1774.

In 1733 Franklin began to publish his annual Poor Richard's Almanack,

offering advice on all sorts of daily matters, along with a multitude

of witty sayings that became catch-phrases of the day. The work (which

ran from 1732 to 1758) was very popular ... whose sales made the

Franklin family quite prosperous. In 1733 Franklin began to publish his annual Poor Richard's Almanack,

offering advice on all sorts of daily matters, along with a multitude

of witty sayings that became catch-phrases of the day. The work (which

ran from 1732 to 1758) was very popular ... whose sales made the

Franklin family quite prosperous.

But his curiosity about life and how it worked did

not stop there. He loved to experiment with better ways of doing

ordinary things, inventing multitudes of new objects along the way,

such as the Franklin stove, bifocals, an elaborate glass harmonica, but

especially things connected with the new idea of electricity (including

eventually the lightning rod, a dangerous venture which killed others

who tried to follow his lead). This latter interest soon had him

considered to be one of the leading scientists of the day, and he found

himself closely involved with the growing scientific community,

especially during his many extensive stays abroad in Europe.

He was no less an inventor in the field of

education, helping to develop in the 1750s a New-Model college

curriculum taught not by tutor generalists but by professional

specialists in different academic fields, and then to see this

curriculum put into play in the new King's College (ultimately,

Columbia University) and the College of Philadelphia (ultimately, part

of the University of Pennsylvania) – the latter which Franklin also

co-founded.

But it was in the field of politics that Franklin

would be best remembered. From the mid-1750s onward, Franklin spent

much time in London as a representative of the Pennsylvania Assembly,

in part to press the case against the autocracy of the Penn family

(Penn's descendants were less generous than their Pennsylvania

founder). But eventually his main concern would come to be over the new

taxes (especially the expensive government stamps required on all

publications) being imposed on the colonies by King George's Tory

Parliament. With his opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act, he became

well-known back in the colonies as a key advocate for a cause that

touched not only Pennsylvania, but all the colonies mutually.

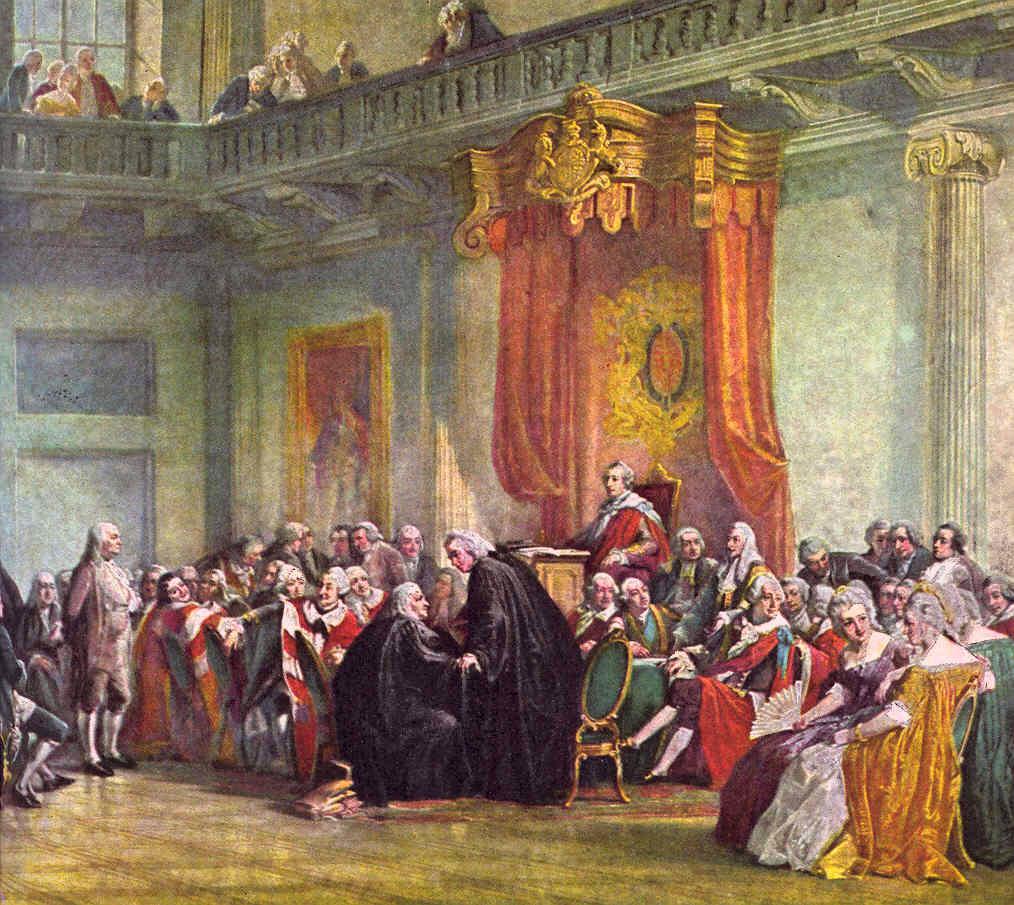

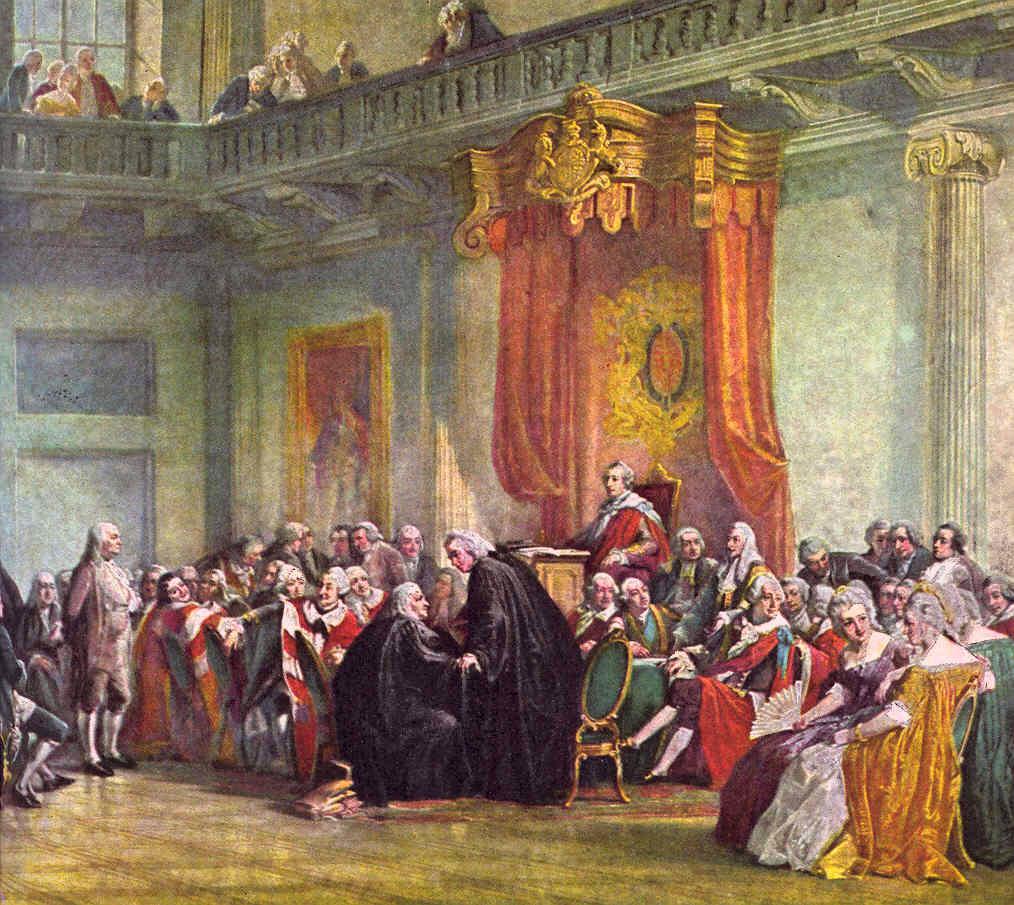

Franklin appearing before the King's Privy Council – 1774

But tragically this would put Franklin in deep

opposition to his son William, who by Franklin's own intervention had

been awarded the position as Governor of New Jersey. This royal

appointment was to make William a very strong Tory leader in the

colonies, at the same time that his father was becoming a leading voice

in the colonies' rising spirit of rebellion. The two would split over

this matter, never to be reconciled.

When Franklin returned finally from London in

1775, the rebellion had already begun, and Franklin was appointed as a

Pennsylvania delegate to the Second Continental Congress, where he was

also chosen to be a member of the five-man committee commissioned to

draft a Declaration of Independence.

But then he was soon sent off to France (1776) to

be something of an ambassador to the French court for the new United

States. Here he not only worked hard to coordinate the French support

of the American rebellion (and its needs for French soldiers and

supplies), but he dazzled the French Court with his (purposely

stylized) rustic appearance and homespun wit and wisdom (John Adams,

who was there with him at the time, found Franklin's folksy theatrics

totally distasteful!). Franklin would remain there throughout the War,

ultimately helping negotiate the Treaty of Paris (1783) in which the

British recognized the independence of the new United States of

America. Then Franklin returned to America in 1785, soon after he and

Adams were joined in Paris by the young Jefferson. This would bring

Franklin back in time to serve (as we have just seen) as a Pennsylvania

delegate to the Constitutional Convention being held in Philadelphia

over the summer of 1787. But then he was soon sent off to France (1776) to

be something of an ambassador to the French court for the new United

States. Here he not only worked hard to coordinate the French support

of the American rebellion (and its needs for French soldiers and

supplies), but he dazzled the French Court with his (purposely

stylized) rustic appearance and homespun wit and wisdom (John Adams,

who was there with him at the time, found Franklin's folksy theatrics

totally distasteful!). Franklin would remain there throughout the War,

ultimately helping negotiate the Treaty of Paris (1783) in which the

British recognized the independence of the new United States of

America. Then Franklin returned to America in 1785, soon after he and

Adams were joined in Paris by the young Jefferson. This would bring

Franklin back in time to serve (as we have just seen) as a Pennsylvania

delegate to the Constitutional Convention being held in Philadelphia

over the summer of 1787.

|

THE

FRAMERS' CHRISTIAN TAKE ON THE ISSUE |

|

The Framers understood the dangers of building only on

ever-changing human logic ... rather than on

permanently-established basic law

Franklin's appeal registered itself as strongly as it did because all

present knew well the Biblical story of the Fall of Adam and Eve from

God's Paradise. Adam and Eve had ignored God's warning not to eat from

the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (human logic), but instead

had followed the Serpent's advice to do exactly that because it would

make them be "like God." The temptation to play God by assuming for

themselves the knowledge of Good and Evil was too great for Adam and

Eve to resist. But in breaking that command, disaster struck. What they

got for their efforts was only a half-truth (the most dangerous of all

lies). Apart from the fundamental guidance of God, their logic could

not guide them except in merely self-justifying circles. It did not

produce true knowledge. Their logic was only technique – not Truth

itself.

Truth came from a deeper source of life – from a

depth that human logic itself could never reach. Only a close, fully

trusting relationship with the Author of Life – and Life's basic Truths

as God ordained them – offered true knowledge. But by their

disobedience, by their questing for knowledge apart from God, Adam and

Eve had ruptured that vital relationship. They were on their own with

their own sophistication (as in the sophistication of the Sophists of

Ancient Athens). But this sophistication only made them all the more

aware of life's shortcomings, especially in others, whom they blamed

for their problems. Ultimately this broken relationship with God ended

in death – their death. Not a pretty picture!

The Framers understood very well the moral of that

story: human logic was not the answer to life's challenges.

Relationship, holding together in a spirit of unity, and holding to God

as the ultimate judge and ruler of life, was the path they needed to

follow. The better way would come if they were willing to submit their

particular self-interests, and the moral and tactical logic man used in

defense of those self-interests, in support of the greater bond that

held them together as Americans – Americans under God.

What they ultimately formulated as their new

American government was a rather simple alliance system that encouraged

them to work together without according too many powers to the system

itself. This new federal system was their response to the challenge.

Even then they knew that this new system would

work only if man's hunger for power (as in Adam and Eve's desire to

play God) was held in check. A deep respect for – and even fear of –

God among the people was the only way they felt that things might stay

on course as they faced the many challenges ahead of them. This was a

component missing in the logical systems of the philosophers, ancient

and modern. It was not missing in the thinking of the Framers of the

Constitution. In fact it held a central or foundational place in their

understanding of things.

For my own part, I sincerely

esteem it [the Constitution] a system which without the finger of God,

never could have been suggested and agreed upon by such a diversity of

interests. Alexander Hamilton – 1787

Of

all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity,

Religion and Morality are indispensable supports.

. . . And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can

be maintained without religion. . . . Reason and experience both forbid

us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of

religious principle. George Washington – Farewell Address, 1796.

We

have no government armed with power capable of contending with human

passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition,

revenge, or gallantry, would break

the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net.

Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is

wholly inadequate to the government of any other. John Adams – to the Massachusetts Militia, 11 October 1798.

The

belief in a God All Powerful wise and good, is so essential to the

moral order of the world and to the happiness of man, that arguments

which enforce it cannot be drawn from too many sources nor adapted with

too much solicitude to the different characters and capacities to be

impressed with it. James Madison – Letter to Frederick Beasley, November 20, 1825

COMPARING THE SIMULTANEOUS AMERICAN AND FRENCH EFFORTS AT REPUBLIC-BUILDING |

|

Contrast the American approach to self-government in 1787 with the

French Revolution which broke out two years later in 1789 – just as the

American Constitution went into effect.

The French were led simply by their belief in the power of human reason

or logic – especially their own logic (that is, the logic of their

political leaders) – which they supposed would produce a Platonically

perfect French Republic.

Tragically, the leaders of the French Revolution had only

bright ideas – and no practical or deeply tested experience in guiding

and directing a society. Nor did the French people themselves have any

understanding of what their role was to be in this new Revolutionary

society.

God played no part in the plans of the French

reformers. Indeed, their mood was generally hostile to the idea of God

(whom they frequently mocked), for they understood liberty as freedom

from religion. They viewed religion, the Christian faith in particular,

as a key component of the very Old Order that they were bent on

overthrowing. They were determined to be ruled not by God but by man –

by man's basic ability to do the right thing, the logical thing.

By way of complete contrast, the Framers were well

aware of the dangers of trusting to merely self-justifying Human Reason

to direct them. They were quite aware that God – whose rules for

human behavior were as eternal as the laws of physics and chemistry –

had to stay sovereign over these United States, or they too would drift

down the "creative" or "progressive" path of Human Reason that the

French Revolutionaries had foolishly taken up.

Totally unsurprisingly to the more pragmatic

Americans, when the French intellectuals attempted to put their

"enlightened" political philosophy to practice – they found themselves

unable to agree among themselves as to what exactly constituted the

right thing, the reasonable, or logical thing. One man's logic was not

another man's logic.

Soon they fell from their Idealism into mutually

hostile intellectual camps. Consequently, the Revolution quickly

collapsed into a murderous chaos. At first

they kept the guillotine busy beheading the old ruling class of the Ancien R gime:

France's king and queen, its barons and aristocrats, its bishops and

clergy, etc. But having overthrown the Old Order ... they could

not agree on what the New Order should look like.

It was at this point that the leading

revolutionary groups, the Girondins and Jacobins, savagely turned on

each other over points of differences in their "pure" thinking ...

sending each other to the guillotine! And thus France fell into a very

bloody period, especially during the years 1793-1794, a period known

today as the French "Reign of Terror." And so it was that the French

"enlightened ones" themselves became the victims of their own

Revolution.

It finally took the dictatorship of Napoleon

(1799-1815) to bring the French under some kind of political order. It

required a new form of tyranny to rescue them from the tyranny of

unrestrained human self-interest – and the reason or logic used to

justify such self-interest.

So much for human Reason and the Idealistic belief

that man's Reason opened the way to some kind of absolute Truth and

Goodness! Yet it would be a sophisticated belief that would never seem

to die, despite the ugly historical record of man's continuing attempts

to build utopias on the basis of human Reason alone.

By way of strong contrast, the Framers of the

Constitution were very aware of such potential dangers.1

Thus the

American "Revolution" they presided over, highly suspicious of

unrestrained human behavior and thus cautiously minimalist in its

utopian efforts, succeeded awesomely in creating a viable republic –

one loaded with many checks and balances in its distribution of various

governmental powers.

And thus it was that the American constitution-building effort

would succeed brilliantly ... to the same extent that the French

Revolution failed miserably.

1Except

probably Jefferson, who anyway was away during the drafting of the new

Constitution, serving as America's Minister (Ambassador) to France

(1785–1789). In Paris, he was wholly enraptured by the reformist spirit

of the French philosophes (intellectuals or philosophers), a spirit

which was clearly driving France toward revolution. Jefferson, being

himself a utopian idealist, long remained a devout defender of the

French Revolution, which finally broke out in 1789 (just before he

returned to America). Indeed, he was one of the last to finally admit

that the murderous Reign of Terror into which France soon fell had

tragically betrayed the original high ideals of the French utopian

philosophers he once so greatly admired.

|

The execution of French King Louis XVI – January 21, 1793

... setting off a realm of mass executions ... first of the French nobility and clergy, then descending down into mutual slaughter of opposing revolutionary groups: Jacobins vs. Girondins

Leaders of the French Revolution

Georges-Jacques Danton, early Girondin leader

replaced by the more radical Jacobin, Maximilien Robespierre

and the Jacobin sociopath Jean-Paul Marat ...

who used to make the list of those to be guillotined during the Reign of Terror

The Goddess of Reason, symbol of the new Cult of Reason (1793)

replacing France's traditional Catholicism. She is being led to the Cathedral Notre Dame where she will be placed at its altar as a sign of the new Age of Reason ... ironically at the same time that the French are slaughtering each other over points of "reason."

Jacobin headquarters during the height of the "Reign of Terror" (July 1794)

The mass-murderer Robespierre himself is finally guillotined (July 28, 1794)

... the beginning of the slowdown of the Reign of Terror

The Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (reigned 1799-1815) finally settles France down... before spinning the country outward in a campaign of European conquest

The Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte (reigned 1799-1815) finally settles France down... before spinning the country outward in a campaign of European conquest

Miles H. Hodges Miles H. Hodges

| |

But with the conversion of Roman Emperor

But with the conversion of Roman Emperor

Indeed, not only was the idea of having their

lands to the West put under Catholic hierarchical authority that

reached to Rome – but also the idea (which was being discussed openly

by

Indeed, not only was the idea of having their

lands to the West put under Catholic hierarchical authority that

reached to Rome – but also the idea (which was being discussed openly

by