9. THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR

1864: THE SOUTH UNDER SIEGE

CONTENTS

Grant takes over the effort to bring Grant takes over the effort to bring

Virginia to defeat

Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley Campaign Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Sherman's March on Atlanta Sherman's March on Atlanta

The Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5-23) The Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5-23)

The Election of 1864 The Election of 1864

Hood attempts to cut off Sherman's line Hood attempts to cut off Sherman's line

of supply

Sherman’s "March to the Sea" Sherman’s "March to the Sea"

(at Savannah - November-December)

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 309-314.

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1864 |

The South under siege

May On the Georgia front, Sherman has advanced his troops south ... to surround the very strategic city of Atlanta

May-Jun With Grant now in command of the Union army in Virginia, Lee finds he is up against an individual that will not back off to rest

following relentless engagements: Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, etc.

Jul But the Virginia town of Petersburg has built strong defenses able to block Union progress

Aug Mobile, the last open Southern port, is brought to defeat by Farragut's Union navy

Sep Sherman brings Atlanta to full defeat

Sep-Oct While Petersburg continues to hold out, Sheridan moves his cavalry into Western Virginia, raiding and crushing the Confederate spirit in the Shenandoah region

Nov Union-occupied Atlanta burns widely

With the war now headed clearly in the Union's favor, Lincoln is easily reelected

Nov-Dec Sherman heads his troops through Southern Georgia to Savannah, capturing Savannah as a "Christmas present" for Lincoln ... and giving the Union full control of the mid-South

|

Abraham Lincoln – Feb 9,

1864

GRANT TAKES OVER THE EFFORT TO BRING VIRGINIA TO DEFEAT |

|

In early 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to

Lieutenant General, giving him command of all the Union armies. Grant

turned his armies (the armies of the Tennessee and Cumberland now

combined) over to General Sherman and headed to Washington to take

command of the entire war effort. His plan was to have Sherman march

south into Georgia from his position at Chattanooga, in order to take

the vital Confederate heartland at Atlanta. At the same time Meade's

Army of the Potomac would attack Lee's Army of Northern Virginia (with

Grant in camp with Meade) from the north and General Benjamin Butler

would attack Richmond coming up from the south along the James River

(similar to McClellan's Peninsula Campaign two years earlier.)

It would be total war, designed to crush

the South's economic and emotional as well as military capacity to wage

war. Under Grant's command the war would be fought very differently,

smaller battles, but one immediately after another, with no letup in

the hits the Union troops were to make on the Confederate troops.

Grant

would continually attempt to swing around Lee's forces, with Lee being forced to give

ground little by little in order not to be flanked or surrounded by

Grant's forces.

Lee now understood that he was in

trouble, with the Union troops unwilling to break off after a battle

but instead hanging onto his troops like bulldogs, wearing the

Confederates down little by little.

The Battle of the Wilderness (May 5-7)

The

two sides met near Spotsylvania in a wooded area with dense underbrush,

that came to be termed the "Wilderness." They bloodied each other

severely, with no clear victor and with huge losses registered on both

sides. Grant’s intent to swing eastward around Lee was met by

Longstreet, who managed to hold off Hancock. Likewise an effort

by Longstreet to reverse the action also failed when he himself was

wounded (by his own men). On the third day of the action Grant

broke off the engagement. But by no means was he in any way

dissuaded from his origin plan.

Spotsylvania Court House (May 8-21)

The next day Grant and Lee met in battle as Grant again attempted to

swing southeast around Lee ... who had retreated to the

crossroads of the Spotsylvania Court House and had dug in there.

When Grant attacked Lee he found that he could not break the four-mile

long Confederate line. He attacked at one well-defended point in

the line (that came to be known as the "Bloody Angle"), losing huge

numbers of his troops in the effort. After 24 hours of brutal

hand-to-hand fighting, after which he accomplished no gains, he backed

his men off. He did not give up the fight but attempted several

other strategies over the next days none of which yielded him any

advantages. The Confederates attempted a counter assault.

But that too turned out to fail. Finally Grant broke off and

headed his troops southeast in another attempt to swing around behind

Lee.

Cold Harbor (May 31-June 12)

Union cavalry had taken control of the crossroads of Cold Harbor, about 10

miles northeast of Richmond and were soon joined by the bulk of Grant’s

army. The Confederates again dug in, creating a line of defense

about 7 miles long. Union attempts to overrun both the northern

and southern extremities of this line failed horribly.

Grant learns some valuable lessons

At the Spotsylvania Court House and Cold

Harbor, Grant learned a lesson that he would not repeat: do not break

off from your adversary long enough to give him a chance to dig in.

Grant's attack on Lee's Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania had proven to be

very costly to Grant, and at Cold Harbor a dug-in Lee proved impossible

to dislodge by direct assault. From this, Grant learned to never again

attempt a direct assault on a well-defended position, as modern arms

give the defenders a tremendous advantage.1

Once again Grant swung his forces east

and south, determined not to give up despite the terrible thrashing his

men had received at both Spotsylvania Court House and Cold Harbor. He

had lost over 52,000 men in the period since he started his Overland

Campaign in early May. But Lee had lost 33,000 men, a much larger loss

proportionately to his total troop size, and thus was much less able to

afford such a high loss.

Meanwhile

Butler’s campaign in the Peninsula had resulted only in his army being

surrounded ... necessitating Grant’s coming to the rescue. But

all the action in Virginia nonetheless tied down Lee in the defense of

Petersburg ... preventing him from coming to the aid of the Confederate

troops trying to hold off Sheridan’s attacks in the Shenandoah Valley

and Sherman’s advance through

Georgia.

Petersburg (July 1864–March 1865)

At this point Grant decided to move his

troops south past Richmond and seize the town of Petersburg, a vital

rail link to Richmond. But Beauregard was able to hold off Grant long

enough for Lee to get his forces in place to protect Petersburg, and a

long Union siege set in. At one point the Union troops dug a long

tunnel under the Confederate lines, then exploded it with the intention

of rushing troops in through the gap in order to seize the city. But

the Union troops were slow to move forward and found that the crater

they had created was so deep that they could not easily move across it,

but instead down in it they had become easy targets for the gathering

Confederates. With this failure, the siege of Petersburg settled down

to a long stalemate.

1During

World War One (1914–1918) European military strategists failed to learn

this same lesson and for four murderous years would throw their troops

into the enemy's grinder of breech-loading rifles, machine guns and

canister artillery, killing hundreds of thousands of troops without

gaining any particular advantage in doing so. They just could not break

themselves free from the habit of designing battles with grand frontal

assaults, as in the day of troops possessing only slow-loading muskets,

in which direct and quick frontal assault was the best tactic in

gaining battlefield victory. In the days of modern weapons this was now

a pointless and murderous tactic to put soldiers through. But the

European generals were slow to figure this out. Grant, however, was not

so dimwitted!

Ulysses S. Grant as Lieutenant General - 1864

Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

Union Gen. George Meade

Union Gen. Benjamin Butler

Union Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

Grant's Headquarters near

Spotsylvania Court House, May 1864

(Grant is third from

left)

Hancock and Staff after Cold Harbor

Winfield Scott Hancock and

staff of the Second Division – Army of the Potomac

Winfield Scott Hancock and

staff of the Second Division – Army of the Potomac

Union artillery equipment

at Broadway Landing – near Petersburg, summer 1964

Library of

Congress

Union mortar used on the

Petersburg defenses

Making wicker gabions as

part of Union siege protection around Petersburg, Virginia

Making wicker gabions as

part of Union siege protection around Petersburg, Virginia

The Confederate prison for captured Union Soldiers – at infamous Andersonville

Prison camp for Union prisoners

at Andersonville, Georgia

- August 1864

Nearly 13,000 of its 45,000 prisoners died from various causes,

from starvation, to disease to pure physical abuse.

National

Archives

Andersonville Prison – August

1864

Library of

Congress

The Union takes its revenge against Lee – using his estate for headquarters ... and ultimately its vast grounds as a cemetery for its dead soldiers!

( Arlington National Cemetery)

East front of Lee's Arlington

Mansion with Union soldiers on the lawns – June 1864

National

Archives

SHERMAN'S MARCH ON ATLANTA |

|

Sherman's March on Atlanta (May–September)

Meanwhile, further to the West, by the month of

May Sherman was ready to begin his assault on the northwestern region

of Georgia. Opposing

him was Johnston and his Army of the Tennessee. Sherman

too preferred flanking movements around the enemy rather than frontal

assaults and thus time and again Sherman would swing (usually to his

right) around the Confederates, forcing them to fall back to avoid

being surrounded.2 And bit by bit this ballet continued, slowly advancing Sherman down through northern Georgia

By July Sherman's army was on the northern outskirts of Atlanta. At

this point the Confederates in Georgia (now under the command of John

Bell Hood) were resolved to give no more ground to Sherman. But six

weeks of attacks on Sherman's forces bled the Confederates greatly.

Furthermore, Sherman had sent troops around to the south of Atlanta,

cutting off Confederate supplies to the city. Realizing that they were

about to be trapped, on the night of September 1st Hood managed to pull

most of his troops out of Atlanta, burning what supplies he had left to

avoid having them fall in the hands of Sherman. Atlanta now belonged to

Sherman.

Atlanta burns (early November)

Hood left a section of Atlanta burned out

because of some of the measures he took to destroy supplies. But this

would be small in comparison to the widespread torching –

indiscriminately undertaken by Union foot soldiers who understood that

there would be no punishment to come their way for acts of arson. In

early November, fires thus swept through Atlanta. Sherman ultimately

did nothing.

Atlanta's destruction demoralized greatly

the Southern spirit. But that too ultimately served Sherman's purposes

quite well. For after all, this was what war was all about: to fight

until such time as your enemy has lost all desire to continue.

2A

notable exception was at Kennesaw Mountain where Sherman attacked

Johnston directly, losing 7,000 troops in the process – whereas the

Confederates lost only 700. The frontal assault thus was a maneuver

that Sherman (like Grant) learned to avoid.

William Tecumseh Sherman

Library of

Congress

Sherman on

horseback

Confederate defenses at the

Ponder House,

Atlanta

Part of Atlanta's defenses – occupied by Union troops after Hood's retreat

Part of Atlanta's defenses – occupied by Union troops after Hood's retreat

The ruins of an Atlanta roundhouse

destroyed by Sherman's men – summer of 1864

National Archives

The Atlanta Depot – blown up on Sherman's Departure

Library of Congress

Atlanta – Confederate Works Northside

Atlanta – Confederate Works Northside

National Archives

THE BATTLE OF MOBILE BAY

(August 5-23) |

|

Meanwhile the North learned of another major

victory against the South. Mobile, at the Southern tip of Alabama on

the Gulf coast was the last major Confederate port east of the

Mississippi still open to the Confederates. Rear Admiral David Farragut

was commanded to seize it.3

Mobile was protected by three forts at

the mouth of its huge bay and a number of Confederate ships in the bay

itself, plus an array of floating mines (called "torpedoes" at the time)

and the ironclad ram CSS Tennessee. Farragut commanded 18 ships,

including four new ironclads. Additionally, 1,500 troops were put

ashore west of the bay to take the western-most fort (Fort Gaines)

guarding the bay.

On the day of the direct assault on

Mobile Bay, Farragut pushed his men to ignore the "torpedoes"4

and get past the forts as quickly as possible. Then the four Union

ironclads took on the Tennessee, which received such a pounding that it

finally brought the ruined ironclad to surrender. With that, the

Confederate fleet was virtually defenseless against the Union fleet,

which now controlled Mobile Bay.

Now Union attention was turned to the

forts, two of which were fairly quickly brought to surrender. The

third, Fort Morgan, would hold out for two more weeks before it too

surrendered. This now left the city of Mobile itself isolated, though

still well protected by Confederate forces.

3Despite Union efforts to blockade the bay, blockade running was still taking place out of Mobile.

4Farragut

was fabled to say "Damn the torpedoes; full steam ahead" though this

was most likely a glamorization of the victory created a number of

years after the event.

Fort Morgan, Mobile Point, Ala, 1864 showing damage to the south side of the fort after its pounding from Union guns

National Archives

SHERIDAN'S SHENANDOAH VALLEY

CAMPAIGN |

|

Lee hoped to draw off Grant by sending (mid-June)

Confederate cavalry under Gen. Jubal Early to relieve the Confederate

troops located in Western Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley – a region

of highly productive farms suffering greatly from Union attacks there.

Early was able to drive back these Union forces, and then continue

north up the valley until he crossed into Pennsylvania. Then he turned

(mid-July) southeast towards Washington, attacking one of the city's

defending forts in the northwest.

At this point Grant dispatched his own

cavalry commander Philip Sheridan to the upper Shenandoah region to

draw Early into battle. As Sheridan marched to meet Early, he destroyed

as he went, attempting to collapse the economy of this region, which

provided much of the food needed by the Confederacy. In mid-September

the two armies met in two battles, with Early taking a beating from

Sheridan in both. Then at Cedar Creek (October 19) Early nearly

delivered a crushing blow to Sheridan ... though Sheridan was able to

rally his troops later in the day and completely reverse the situation.

After yet another major battle

(October 19th) in which Early was defeated, both Early and Sheridan

broke off their contest and headed back to join their respective forces

at Petersburg. ... until at Cedar Creek (October 19) Early delivered a

crushing blow to Sheridan ... though Sheridan was able to rally his

troops later in the day and completely reverse the situation. In

fact, the result of this encounter left Early with such a badly

crippled army that Sheridan was able to move his army east and rejoin

Grant at Petersburg. The Shenandoah would no longer concern the

North ... having been fully neutralized by Sheridan’s actions.

|

Philip Sheridan and other

Northern Cavalry Generals – 1864

Sheridan at Cedar Creek,

VA prior to his ride to Winchester – October, 1864

|

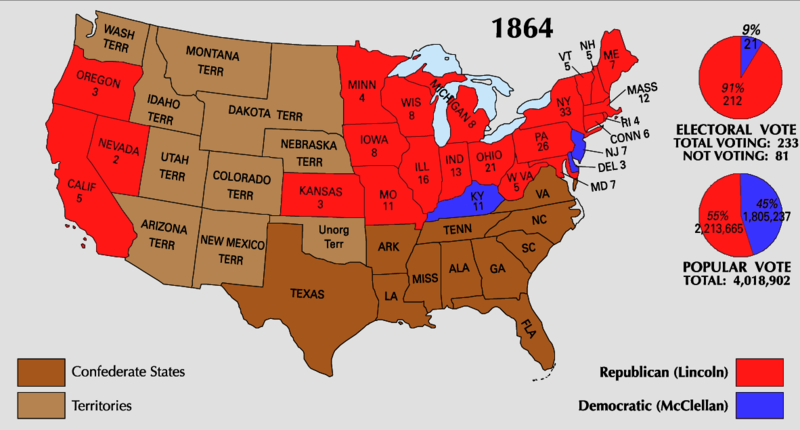

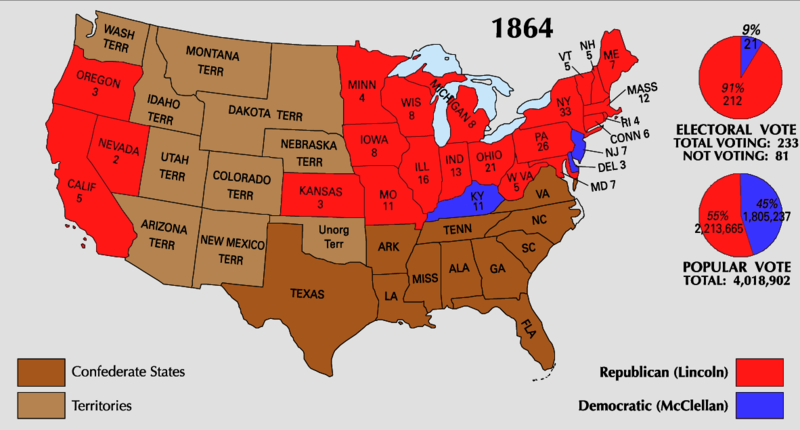

Things

had looked quite negative for Lincoln in the early months of 1864 as

both the Republicans and Democrats made preparations to choose

candidates for the presidency. No president had been re-elected since

Jackson’s re-election in 1832. The Abolitionist Radicals had

created a new party and Frémont was named its presidential

candidate. Also some "War Democrats" joined the Republicans in

refashioning the Republican Party as the National Union Party, with the

intention at first of nominating someone other than Lincoln, most

likely Salmon Chase.

But Lincoln was still widely

popular among Republican politicians and Chase stepped aside once that

became clear. In early June Lincoln was thus named the

presidential candidate for the National Union (Republican) Party, with

Andrew Johnson, a Southerner loyal to the Union (and military governor

of Tennessee), named as his running mate. On two key points the

Party's platform was quite clear: unconditional surrender of the

Confederacy and a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery

everywhere within the U.S.

The opposing Democratic Party was split

between War Democrats and Peace Democrats, the former continuing to

support the war as it stood, the latter demanding a negotiated peace.

The Party finally created a compromise, by nominating the popular

General McClellan as a War Democrat for president, and anti-war

Congressman George Pendleton as their candidate for vice president. But

the balanced ticket only confused Americans as to what exactly the

Democratic Party's intentions were if the McClellan-Pendleton

combination were elected to office.

In any case, by November's elections, things had turned very favorably

for the North. Lee was clearly on the defensive deep in Virginia,

Mobile Bay had been taken from the Confederates, Sherman had conquered

Atlanta and the Shenandoah Valley had been neutralized. The North

seemed clearly to be winning the war and thus Northern voters were now

swinging strongly behind their president.

Thus in the elections, Lincoln won the

popular poll by over 400,000 votes and the electoral college tallied

212 votes for Lincoln and only 21 for McClellan.5 Americans clearly wanted Lincoln returned to office for four more years.

5Of course the eleven Southern or Confederate states still in rebellion did not participate in the election.

HOOD ATTEMPTS TO CUT OFF SHERMAN'S LINE OF

SUPPLY |

|

Confederate Gen. Hood swung from Alabama into Tennessee in an attempt to draw

Sherman back north away from Atlanta. But Sherman had other

plans, and instead sent Thomas north with some of Sherman’s troops to

take a stand against Hood at Nashville.

Hood's

attempt to cut off Thomas’s movement failed. He suffered severe

casualties at Spring Hill and Franklin, Tennessee, in late November and was

completely humiliated two weeks later at Nashville when a massive

attack by Thomas drove him and what was left of his army back to

Mississippi. No further attempts against the Union armies would

be coming from that

direction.

Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood

Union General George Henry Thomas

SHERMAN'S "MARCH TO THE SEA" AT

SAVANNAH

(November-December) |

|

The next move was designed by both Grant and

Sherman with a dual purpose: to cut a wide swath of morale-crushing

destruction through the heartland of Georgia, one that reached from

Atlanta all the way to the Atlantic port of Savannah, and then turn

north in order to put such pressure on Lee in Virginia that this would

allow Grant to finally break the stalemate at Petersburg.

The plan was to break free from the need

to maintain a supply line to the Northern troops and simply (and

brazenly) to disappear with his army into the midst of enemy territory,

living off the land by foraging widely (at times about sixty miles in

width) from the local economy as they went. And they were to destroy

local infrastructure (bridges, rail lines, telegraph lines, mills,

barns) in areas where they ran into resistance.

Unfortunately for the South, Hood's

decision to abandon Atlanta and retreat into Tennessee in the hope of

drawing Sherman off in that direction had greatly reduced the South's

ability to hold off Sherman's invading army as it headed toward

Savannah. Sherman, in the meanwhile, had succeeded in keeping the South

confused as to his ultimate destination.

With little Confederate resistance,

Sherman's army reached the outskirts of Savannah within a few weeks of

its departure from Atlanta. There Sherman's army linked up with Union

Admiral Dahlgren's fleet, and the two Union forces began to attack

Savannah from both land and sea. Sensing the trap, the Confederate

forces defending the city escaped by the one route still open. Thus on

December 20th Sherman marched into the city to receive its surrender,

under the promise – which was honored by Sherman's troops – not to

destroy the city. Sherman was pleased to present Savannah to Lincoln as

a Christmas present!

|

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com

Illinois Union troops destroying

railroad tracks as Sherman begins to move past Atlanta – November

1864

Sherman's men destroying

railroad

tracks

The method of destroying

railroad tracks: burning them with their

cross-ties

Slave market in Alexandria,

Georgia, captured by Union forces – 1864

| | | | | | |

Grant takes over the effort to bring

Grant takes over the effort to bring Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley Campaign

The Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5-23)

The Battle of Mobile Bay (August 5-23)

Hood attempts to cut off Sherman's line

Hood attempts to cut off Sherman's line Sherman’s "March to the Sea"

Sherman’s "March to the Sea"