13. WESTERN RATIONALISM

DARWINISM ... AND MARXISM

Darwinism

Darwinism

Elitist intellectuals versus middle-class

Elitist intellectuals versus middle-class

commoners

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 402-415.

DARWINISM |

|

When in 1859 Charles Darwin published his book, On the Origin of Species – the culmination of years of research and earlier publications – he shook the moral foundations of Western civilization. This occurred not because Darwin invented a new worldview out of thin air. The ideas of progress through struggle were by this time rather widely accepted. The British Whig party, in fact, was built on this idea: that Britain should be run by those proven strongest in life's competition and that no tears should be wept for the poor swept aside by life's struggles, because that would only hinder human progress. No, it was not the newness of Darwin's

ideas that made his works so spectacular, but it was because he gave

such precise explanation – and justification – to these Whiggish ideas.

His great contribution to this debate of worldviews was that he built

his Darwinist theory of life on a vast field of scientific evidence,

something that had by that time become the absolute requirement for any

claim to Truth. Robert Malthus … and early versions of "survival of the fittest"

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck ... and genetic progress

An earlier Darwin

It is important to note that Lamarck was himself influenced by Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, who in 1796 described in his publication Zoonomia how species had developed slowly over the generations by their abilities to pass on from generation to generation not only their basic traits, but also useful alterations in those traits. Thus Erasmus's grandson Charles Darwin came from a family already securely located in the evolutionist camp! Darwin himself

Thus every living creature we saw around us was naturally evolved from a less complex ancestor by a process termed "natural selection." In short, morally speaking, life was at its core simply a matter of the survival of the fittest. Herbert Spencer

Soon Spencer would even outdistance Darwin as the most recognized philosopher of the late 1800s. But the very names Darwin and Darwinism would still serve as the most powerful symbols able to raise strong debate, pro and con, not only well into the 20th century but still even today. Nietzsche

He also was distinctly an atheist – informing the world that "God is dead." He (like Marx) saw the Judeo-Christian religion as offering humanity only enslavement to earthly commonness by teaching people to aim not for greatness in this life – but instead to aim for some supposed afterlife that Judeo-Christianity claimed awaited the humble and faithful at death. Nietzsche was very emphatic in stating that there was no evidence whatsoever that such a Heavenly life actually existed. Darwinism in the late 1800s

In any case, all of this debate rising in the late 1800s helped to shape the rising spirit of the times ... with Darwinism’s clear message to all: the past is dead and to be put behind us. We need to move forward boldly into the future with all of its promising possibilities. We must not become unnerved by the process of change itself. We must not let our progress be handicapped by a clinging to old superstitions and cultural habits of the past. Darwin's theory fit well with the interests of the evolving industrial class, the British Whigs, who dominated fast rising British industry ... and who also pushed for their entry into the British social status system that long held absolute control over British society. This ancient status system had accorded social superiority or privilege only to those with long family pedigrees and a landed estate of some considerable acreage that had been passed down from generation to generation. Breaking into the ranks of those highly privileged within the British class system was virtually impossible if you were not already a member of it by birth. Those who tried to enter the realm of the British aristocracy through simply the demonstration of newly acquired wealth were considered by the aristocracy merely as vulgar upstarts unworthy of social recognition ... no matter how vast their newly acquired wealth.

What Darwin – or more precisely his followers, especially social-theorist Thomas Huxley (who actually coined the phrase "survival of the fittest") – put in the hands of the Whigs (or Liberals) was the demonstration that in fact life by its very nature was designed not to protect tradition but to reward those who demonstrated vastly superior life skills in the way that they secured success in the face of a very competitive environment. These were the people, by nature itself, who were destined to lead ... not the leisured aristocrats who clung to social privileges merely brought forward from the past. These inherited privileges served no useful social purpose ... and should be dismissed in this highly competitive world. The strong should rule. And government should not intervene in the process ... but instead step aside. Society needed to be liberated from the restraints of custom ... and especially by the political and social habits of the State. Thus English Liberalism was born as a distinct social doctrine of the Whigs ... eventually leading to the creation of the English Liberal Party itself.

Some of the Darwinists were even to take the position that the strong have the natural right to rule over the weak – the latter who in life’s natural competition should not only be allowed to fall by the wayside but in fact should not be supported at all by any special favors coming from the strong ... because this would impede the natural process of social progress, which England (and the entire West) was certain was well underway. As an Anglican clergyman, Malthus himself had wrestled with the problem of why God would allow suffering to occur within his creation. Malthus finally concluded that God wanted man to rise to the challenge of life, to succeed in the face of life's difficulties through the discipline of hard work. Those who fell short of the challenge were simply some kind of disappointment to the great Creator.1 Those who failed merely reaped that which they had sown. This in essence was the British version of Sturm und Drang! Malthus's explanation of course was a terrible reading of what the founder of the Christian faith himself had taught the world. Jesus put the challenge not in terms of natural selection, but quite the opposite. According to Jesus, the challenge of life was to find ways to help the poor in the face of the huge challenge of survival in a competitive world of economics and politics. This ability to do charity, when the opposite would be so much more tempting, was for Jesus the measure of greatness of anyone in God's kingdom. At some point people were going to have to choose between the two, Jesus or the Darwinists. The original Puritans had chosen Jesus, and built an experimental society of mutual service among social equals based precisely on the spiritual ethics of Jesus Christ. The Virginians, not exactly Darwinists but of the same mindset, chose instead personal success at the cost of others (the slaves). Thus by the mid-1800s this was not a new issue. It is simply that Darwinism finally gave aggressive selfishness the moral justification that an increasingly aggressively selfish society seemed to require. But Darwin himself, very sensitive to the

importance of human charity and mutual concern in human society, was

quite aware of this ethical matter, and actually troubled by how many

were choosing to read cruel ethical justification into his theories.

1It is truly amazing the extent to which man can go in rationalizing about God and God's intentions.

In 1848 Marx published his famous 30-page Communist Manifesto in the hope of capitalizing on the spirit of political rebellion that was rocking continental Europe at that time. His Manifesto

outlined history as a series of quite Hegelian dialectical struggles

over time between those who legally owned the land, tools, machinery

(what Marx summed up as social property or the "means of production")

that produced the wealth that the people of society lived off of, and

those (the proletariat2) who, though they owned none of those means of

production, labored physically in using those means of production to

bring forward the wealth that society lived off of. Typically in

history, in the distribution of the wealth that a society jointly

created for its survival and prosperity, most all of that wealth went

to the class of property owners, with very little making its way to the

hands of the proletarian workers. This would bring tremendous tension

to society, which eventually would turn into physical conflict because

of this social injustice. Again, in Hegelian (and eventually Darwinian)

dialectical fashion, such conflict or class struggle would then move

history forward to a new, and better social system, shaped by the way

the opposing classes synthesized their social positions into a new

social structure.

In his analysis, he carefully described

the situation around him in Europe where the feudal system, once

dominated by landed aristocrats, had been challenged by a new social

class of industrial and financial capitalists, thus creating the age of

capitalism. But he also saw how capitalism in turn had created its own

opposing social force in the form of the industrial workers (the

industrial proletariat) whose labors supported the capitalist system.

And he predicted that conditions were quickly rising that would cause

the industrial proletariat in its turn to rise up against the

capitalist class, and through the necessary historical conflict or

revolution open the way to a new social system. Time was on the side of the worker,

because capitalism by its very nature is highly competitive even among

the capitalists themselves – each capitalist trying to eliminate his

competitors in order to gain greater control over the market. This way

they could increase their profits, even establish total or monopolistic

control over the whole process. But of course as they drove each other

out of business, they were inadvertently thinning out their capitalist

social ranks, making their numbers smaller at the same time that the

ranks of the proletariat were growing. Thus simply the calculus of the

few against the many meant that the days of capitalism were numbered.

At that point (which supposedly was now upon them) all the proletariat

had to do was rise up and seize control of the means of production,

thus destroying the power of the capitalist class, and the public

government that had been protecting the capitalists. Thus in rising up

against their capitalist oppressors, they had "nothing to lose but

their chains." But, according to Marx, the resultant

social system would be different, it would be utopia itself. There

would be no further class of dominators or exploiters of the

proletariat, because the new society would be made up solely of

industrial workers. There would be no other class of people in the new

society but this one single industrial class. Everyone would now live

as social equals – as comrades, rather than as a two-class system of

gentlemen lording it over a servant class. Being equals, all would live

communally, as in all land, tools and machines being owned jointly by

all – and by nobody in particular. Consequently, there would be no need for

the political enforcing agency of the state or government. It would

simply wither away, because the sole purpose of the state was to

protect the interests of the privileged class of property owners,

whether feudal, capitalist or whatever. In the communist society there

would be no personal property, thus no state. Something like a

Rousseauian bliss would then hold this happy world together. Also, the new society would end the long

historical dialectic of a ruling class and a proletariat class finding

themselves once again in conflict. With no division under communism

between a propertied class and a proletarian class, there would be no

cause for social conflict, no tension, no stress, only blissful peace.

Thus this last historical revolution would bring history to a

completion, the kind of millennialist completion that everyone was

expecting because of the unprecedented progress they had been observing

coming forth at mind-boggling speed. All history was supposedly about

to fulfill itself, and Marx was showing how that was to be accomplished. This was all pretty powerful stuff. And

it appealed to the interests not only of European industrial workers,

but also to intellectual Progressivists – not only in Europe but also

in America. Marx's theories seemed to be irrefutable because they were

built on hard fact. Unlike the philosophical speculations of social

philosophers before him, but quite like Darwin, Marx had thrown a lot

of data into his analysis, supposedly hard economic data, thus

qualifying his theory as "scientific socialism," making him – and those

who followed his lead – "scientific socialists." As all materialists or mechanists, Marx

had no need of the concept of God, or some divine hand driving forward

the economic process he had outlined. It all worked – similar to

Darwin's theories – entirely mechanically. Marx personally was an

atheist. In fact he was quite opposed to the Christian religion, or any

religion that saw history shaped and judged by a Supreme Being. As for

Christianity, he saw the religion simply as a cruel psychological tool

used by Europe's ruling classes (most lately the capitalists) that

savagely exploited their own servants or workers, by excusing their

horrible treatment of the workers under the promise that if the

oppressed workers all cooperated with the system and behaved themselves

(not rebel against their oppressors) they would be rewarded in the next

life with heaven. To Marx, such religious theory was only a form of

spiritual opium given to the masses to keep them docile.

Even though America was going through the

same process of social industrialization as Europe, America really

never connected with Marxism the way Europe did. Marxism had virtually

no place in the semi-feudal South, and even in the industrial North it

gained only a marginal position among the American industrial workers.

Intellectuals took an interest in it, largely because of its utopian

features. But in general Americans developed their own versions of

intellectual utopianism, quite apart from Marxism. There would be some

similarities, which would get these intellectuals in trouble,

especially during the Red Scares that hit America from time to time. But by and large, America did its own

thing. From their very founding, the New England and mid-Atlantic

colonies had been opened up, settled, and defended not by resident

kings and feudal lords but by a huge class of commoner individuals and

their families – giving American culture its individualistic character.

With America's expansion west across the Appalachian Mountains, the

rural Midwest and the frontier West were settled by the same type of

very individualistic Americans. To these proud Americans the very idea

of giving up their independence to some kind of hovering governmental

institution was itself anathema. Socialism – or government by a

politically entitled set of enlightened supervisors – would not gain

ground in America ... until the second half of the 20th century. But we

will have more – much more – to say about that in the next volume of

this historical study. Meanwhile, as Europe headed into the

Twentieth Century, clearly a growing number of social and political

philosophers were convinced that, through some kind of Darwinian

process, Western civilization (and, via the West, also world

civilization as well) was moving into a bright future in which utopian

existence for all – even (and especially) the unwashed masses – seemed

to loom into view. Society just needed some adjustments here and there

– led of course by these political philosophers or social scientists –

in order to bring this process to completion. "Historical progress" and

"democracy" – however conceived specifically (and the variation was

indeed huge) were the bywords, the slogans, the shibboleths, of those

who supposed that they possessed special intellectual insights into

where the world was headed. Within

that group of Western social

reformers was a large group of Marxist ideologues and political

activists – forming the Social Democratic Party in a number of European

countries – whose expectations were that Marx's Communist revolution

would soon break out across Europe. This supposedly would occur

naturally first in a society experiencing the most advanced state of

capitalism, probably Great Britain or Germany. After all, Marx's

scientific socialism would not work except under the historical

circumstances he had so carefully described. Every stage of historical

development had to be completed before history would be ready to move

on to the next step or phase in its development. The dialectical method

demanded that kind of historical precision.

2A

term drawn from Roman times in reference to the members of the Roman

working class who held little or no property and thus few or no

political rights.

However members of the West's property-owning

middle class – and certainly that included the vast number of

middle-class Americans – loved their private property and not only had

no interest in the idea of intellectuals taking command of society in

order to bring their world to some kind of utopian property-less

democracy but were positively horrified at the idea. Indeed, in Puritan America (colonial New

England) it had been well-understood that property ownership was

crucial to the development of a sense of social responsibility, which

is why new Puritan settlements were designed with small but equal

property allotments given to each new family joining the community.

Thus it was that – to what eventually became Middle-Class America – the

ownership of a home and adjoining property was an absolutely

foundational principle never to be violated. Any talk about removing

property rights of the people was absolute anathema to such Americans,

and a key part of the fear or Red Scare that would occasionally sweep

America when intellectuals were heard talking of social property rather

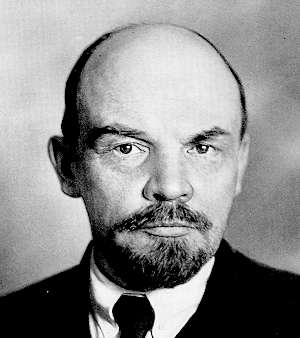

than private property. In any case, Marxist-Leninist ideas were

rampant in Western intellectual circles, especially with Lenin’s

successful overthrow of Russia’s very brief middle-class democracy and,

as a result of the very brutal Russian Revolution and Civil War of

1917-1921, the installing in its place of a Communist working-class

democracy ... a "democracy" directed and controlled by Lenin’s

Communist Party elite, of course. Indeed Lenin – and his chief partner and

heir-apparent, Leon Trotsky – intended their Russian Revolution to be

merely the first phase of a larger, world-wide revolution designed to

sweep away bourgeois, middle-class culture and society and replace it

everywhere with a Communist working-class society – directed by the

vanguard of the proletarian revolution, the Communist Party elite. And it looked for a while as if they

might actually succeed in spreading their revolution, at least to the

defeated powers of the Great War, Germany and Austria-Hungary, when

Communist uprisings occurred in the capitals Berlin and Budapest. Thus while Marxist-Leninist thoughts

delighted a good number of Western intellectuals, who found it easy to

identify with such high ideals (and such marvelous political

opportunity for themselves as society's managers), it set off a Red

Scare among the comfortable middle classes of Western societies

everywhere. And thus also a serious social cultural

breach between intellectuals and Middle-Class or bourgeois commoners

began to grow within Western society, especially in America. A battle

between "high-brow" intellectuals and "low-brow" commoners3 was

beginning to form. The battle would become intense and bitter – and

rather persistent through the rest of the 20th century (and even still

today).

3Or

"a basket of deplorables," as Democratic Party presidential candidate

Hillary Clinton labeled them in a September 2016 campaign speech.

We need to include another political philosophy

that developed along these same lines towards the latter part of the

1800s, Anarchism. Anarchism was not a movement or an ideology. Instead

it simply was a mood that infected European politics as the familiar

feudal world began to fall apart and as the emerging post-feudal Europe

was not yet moving towards any set social form or structure. Anarchism

might be considered Rousseauian. It might be considered Marxist. Both

philosophies stressed how a better world would be one in which the

little people led their lives without having to live under powerful

overlords who wanted to control their lives. But anarchists were not

the type to wait for revolution to develop. They simply took matters in

their own hands, and assaulted those leaders themselves. In short, they

were simply assassins assuming the heroic responsibility of removing

evil overlords from society, or else they were just socially

maladjusted individuals, bitter because things were not working out for

them socially and taking their sense of vengeance out on the leaders

who symbolized an uncaring society. In any case there would be a rash of

anarchist events in Europe in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and even

in America (President McKinley was shot and killed by one). In fact it

was a small group of anarchists (believing themselves also to be

loyal Serbian nationalists) who, in assassinating the Austrian Grand

Duke and his wife in 1914, would set off a huge war that brutalized and

ultimately crippled European civilization itself. |

Since the publication in 1798 of the book

Since the publication in 1798 of the book  Going at the issue of evolution from a different perspective, the Frenchman Jean Baptiste Lamarck had concluded in his 1809

Going at the issue of evolution from a different perspective, the Frenchman Jean Baptiste Lamarck had concluded in his 1809  Darwin himself. What Charles Darwin had achieved in his 1859 book

Darwin himself. What Charles Darwin had achieved in his 1859 book  Darwinism

was further buttressed by the writings of other social philosophers of

the day. Besides Darwin's pupil Huxley, who actually coined the term

"survival of the fittest," there was Huxley's friend Herbert Spencer,

who had been moving in the direction of Darwin's thinking even before

Darwin published his first work in 1859. Spencer had been working on

both social theory (his 1851

Darwinism

was further buttressed by the writings of other social philosophers of

the day. Besides Darwin's pupil Huxley, who actually coined the term

"survival of the fittest," there was Huxley's friend Herbert Spencer,

who had been moving in the direction of Darwin's thinking even before

Darwin published his first work in 1859. Spencer had been working on

both social theory (his 1851  The

German philosopher and writer Friedrich Nietzsche was not exactly a

Darwinist, but certainly was – or would soon become – a voice of his

times (the late 1800s), a period deeply steeped in the Darwinist

mindset. In his multi-volume series

The

German philosopher and writer Friedrich Nietzsche was not exactly a

Darwinist, but certainly was – or would soon become – a voice of his

times (the late 1800s), a period deeply steeped in the Darwinist

mindset. In his multi-volume series

Yet oddly enough Marxism was very popular among a

number of intellectuals in Russia, where industrial capitalism had

barely got itself underway as it slowly emerged from under the Russian

feudalism that still largely dominated the Russian social scene. Surely

by Marxist logic, Russia was hardly ripe for revolution.

Yet oddly enough Marxism was very popular among a

number of intellectuals in Russia, where industrial capitalism had

barely got itself underway as it slowly emerged from under the Russian

feudalism that still largely dominated the Russian social scene. Surely

by Marxist logic, Russia was hardly ripe for revolution.