15. THE "ROARING 20s"

AMERICA AND THE WORLD

CONTENTS

The League of Nations: Wilson's The League of Nations: Wilson's

utopian project

America's approach to the larger world America's approach to the larger world

of global diplomacy

The court martial of General Billy The court martial of General Billy

Mitchell

European political developments lead European political developments lead

the world in the opposite direction

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 496-504.

THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS: WILSON'S UTOPIAN PROJECT |

|

There had been a number of voluntary diplomatic

councils in Europe's recent history (the Congress of Vienna in the

early 1800s, the various Geneva Conventions on the rules of war during

the 1800s and early 1900s, an Inter-Parliamentary Union in the late

1800s) – but Wilson's dream of having the major countries of the world

joined in a permanent, on-going diplomatic union was quite a dramatic

development. Wilson's hope had been that the world was ready to enter

into a whole new era of diplomatic reason – in strong distinction to

the uncontrolled passions that had so recently driven much of the world

into the Great War. Wilson's hope was that nations would instead first

seek international understanding through negotiations, before letting

the heat of national hurt propel them to take up war against another

nation. It seemed like a very good idea – very sensible and logical.

But as things soon demonstrated it was a quite unrealistic dream.

The concept of collective security

It was hoped that reason would bring

national disputes to settlement. But failing that, it was assumed that

collective security would force war-prone nations to back down and

behave, thus preserving the international status quo or world order.

The supposition was that all nations loved world peace – and would by

instinct come together to gang up on a would-be violator of that peace.

That was the heart of the idea of collective security. But in fact, the

instincts of nations, the way they viewed the international status quo

or world order from their own particular point of view or national

interest, varied quite widely from country to country. As it turned out

there was nothing automatic about how collective security worked –

especially when one or another of the world's major powers was

involved. Nations always tended to decide on the basis of their own

sense of national sovereignty how they wanted to approach a particular

dispute.

By no means was there some single

rational point of view that all nations automatically came to hold when

faced with a dispute. Thus the idea did not work – except in a few

minor cases in the early years of the League when the national

interests of the members were not deeply affected by the dispute. But

as international politics headed into the 1930s things got very tense –

and the League not only was not able to resolve disputes that arose

during that period, in attempting to do so the League nearly always

drove one or another major power to resign from the League.1

The League of Nations was based in Geneva

(Switzerland) and consisted of a number of diplomatic organizations,

the most important of which were the League Assembly and the League

Council. The Assembly was made up of a voting representative of each of

the (50+) members. It could take up for consideration any issue it

chose – and Assembly decisions required only a simple majority for

passage of a League resolution. The League Council however was expected

to be more the enforcer of the peace and was a smaller body at first

with four permanent members (Britain, France, Italy and Japan); it had

been expected that America would be the fifth – but America never

joined the League. Eventually Germany was added to League membership

and became the fifth permanent member. Non-permanent members elected by

the Assembly were at first four in number and eventually expanded to

ten in number, each serving for a three-year term. Decisions of the

Council were understood to be weightier matters and thus a resolution

required the affirming vote of all the members (a unanimous decision)

unless one of the Council members was a party to a dispute – and then

that nation was not entitled to vote.

There was also a Permanent Court of

International Justice set up in The Hague (Netherlands) where cases

could be put before highly trained international judges as a way of

settling disputes. This recourse was used frequently during the 1920s.

But as international disputes took on a more warlike nature the PCIJ

was used less and less in the 1930s. (The PCIJ was nonetheless highly

respected and was one of the several League organizations that was

carried over as part of the new United Nations when it was set up in

1945).

There were also other organizations set

up as part of the League – bureaucracies that were supposed to tackle a

number of distinct problems in the area of labor, health, education,

women's rights, drug trade, slavery and other social conditions and

issues. This idea of government action undertaken by technical

specialists was in keeping with the rising spirit of Progressivism in

America and Socialism in Europe in the early 1900s.

1A

number of major powers party to disputes, in finding decisions going

against their national interests, simply resigned: Japan (1933),

Germany (1933), and Italy (1937). Soviet Russia was expelled by the

League in 1939 when it refused to call off its invasion of Finland.

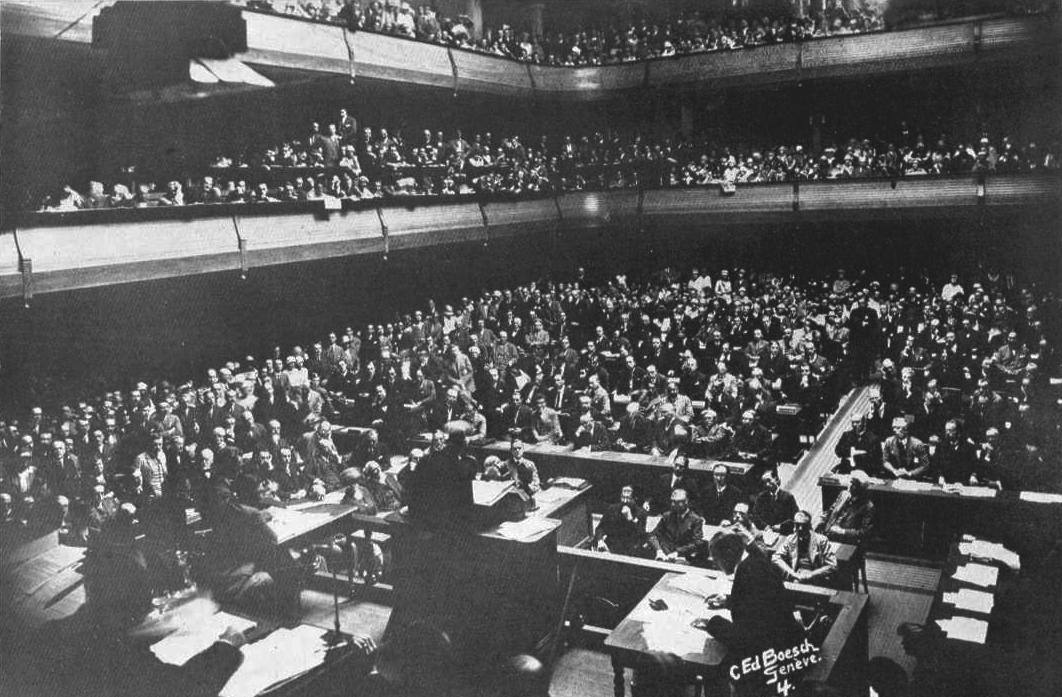

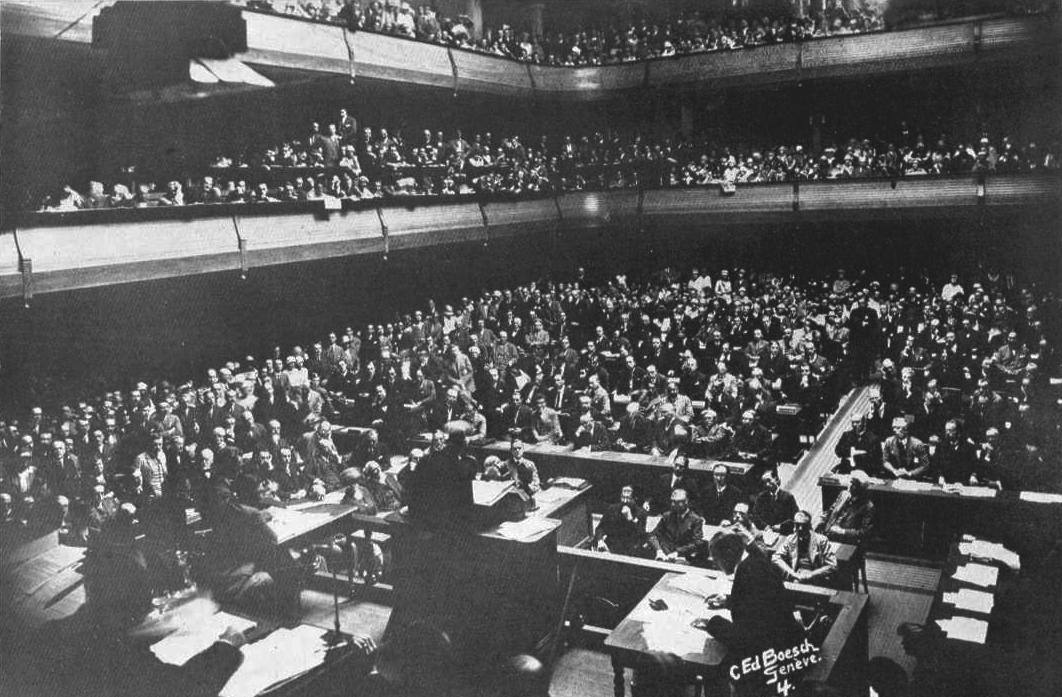

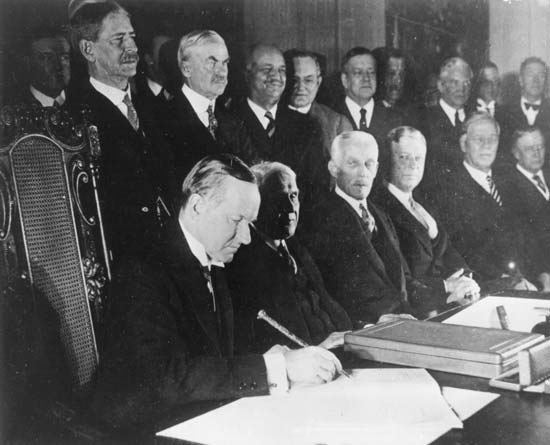

The League's Palace of Nations – Geneva

The September 10, 1926

meeting of the

League of Nations on the occasion of Gemany's

entry into the

League. Foreign Minister

Gustav

Stresemann of Germany is addressing

the Assembly with his initial

speech.

AMERICA'S APPROACH TO THE LARGER WORLD OF GLOBAL DIPLOMACY |

|

American isolationism with respect to entangling alliances

America had refused to join Wilson's League of

Nations. Americans in general had come to feel that there had been a

huge betrayal at the end of the Great War by the Wilson government and

by their English and French allies. Both Wilson and America's allies

had failed to make good the promise of the spread of democracy to the

whole world – and thus of world peace (for why else indeed had

Americans gone to Europe to die?). Consequently, there was virtually an

immovable resolve of Americans never to get involved again in the

dangerous hypocrisies of another European conflict. This isolationist

sentiment with respect to the events in the European Old World seemed

unshakeable.

However … a participant in the world disarmament movement

Americans per se

were not opposed to peace itself – only to entangling alliances that

would compromise the freedom of the nation. This mood therefore did not

mean that America would not participate at all in the matter of

securing a peaceful world. In the post-war 1920s America in fact was

quite active in this regard.

The horrors of the Great War had been so

terrible that a widespread sentiment among many of the victor nations

was that henceforth – except for very dire defensive reasons – war was

virtually unthinkable. This encouraged the utopian reasoning of

European and American Idealists who sincerely believed that indeed the

Great War had ended up being the war to end all wars. Supposedly

peaceful reasoning had developed within world culture to the extent

that passionate militarism was a dead thing of the past. "International

understanding" was now the driving force within the new diplomacy.

Accompanying this general hope was the

widely-held view of the times, both in America and Europe, that the

greatest danger to the peace that the world craved so deeply was to be

found in the heavy militarization of the nations. "Take the weapons

away and the nations will be forced to act peacefully with each other."

Thus the word of the day was disarmament.

When Germany was forced to agree to a

huge cutback in its military as required by the Versailles Treaty, the

Germans were led to believe that this was not intended as punishment

but instead as the first step in a larger disarmament of all nations.

On that basis the German negotiators seemed to be accepting of the

disarmament terms imposed on them.

The Washington Naval Conference (1921–1922)

Seeking the same goal, America during the

winter of 1921–1922 hosted a great disarmament conference at its

capital. This conference was designed to set international standards

and limits on the size and functioning of the navies of the major

powers involved in the politics and diplomacy in East Asia and the

Pacific Ocean, and also other subjects designed to reduce the horrors

of war, such as the outlawing of the use of poison gas. Importantly the

conference was designed both to recognize the role of the Japanese navy

in this region while at the same time to set limits to just that role.

It also set out to prevent any kind of naval arms race from developing

among any of these powers, thus agreeing to limit the building of naval

vessels at a ratio of 5:5:3 for Britain, America and Japan, these

numbers reflecting the relative size of each nation’s maritime activity.

But beyond this naval accord, the powers

were not able or willing to go in reducing the size of their military

forces, France being especially nervous about reducing its military in

the face of a Germany that would surely one day rebuild. Subsequent

protests from the Germans that no serious moves were being made to

bring other countries in line with Germany's level of forced

disarmament ultimately fell on deaf ears.

Instead

another approach was made to the ideal of world peace. In 1925 Germany

was admitted to the League of Nations – recognizing it as a major power

with a permanent seat on the League Council.

|

Europeans ascending the

steps

to the U.S. State, War and Navy building in 1921 Europeans ascending the

steps

to the U.S. State, War and Navy building in 1921

to begin the Washington

Naval Conference – designed to set limits on naval fleets

National Archives

NA-111-SC-80612

Delegates of the nine nations

participating in the Washington

Naval Conference – 1921-1922

|

The Locarno Agreement (1925)

And

in that same year Germany was a major participant at a diplomatic

conference held in the Swiss Alpine city of Locarno. The Locarno

Agreement contained the promise of France, Britain, Germany, Italy and

Belgium that they would not resort to war in their relations with each

other, but would resolve their conflicts only by peaceful means.

Locarno thus gave hope that Europeans might be ready to move to more

serious thoughts on military disarmament.

|

Signing the Locarno Treaty -1925

|

The Kellogg-Briand Pact (1928)

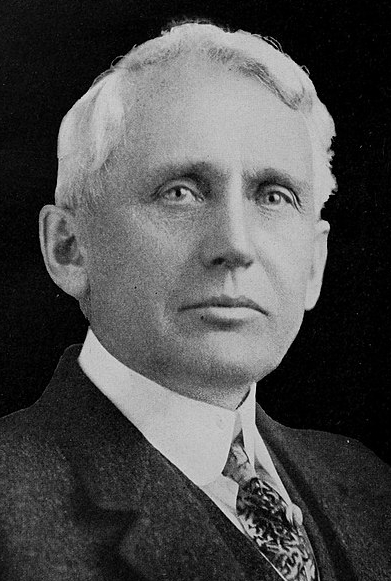

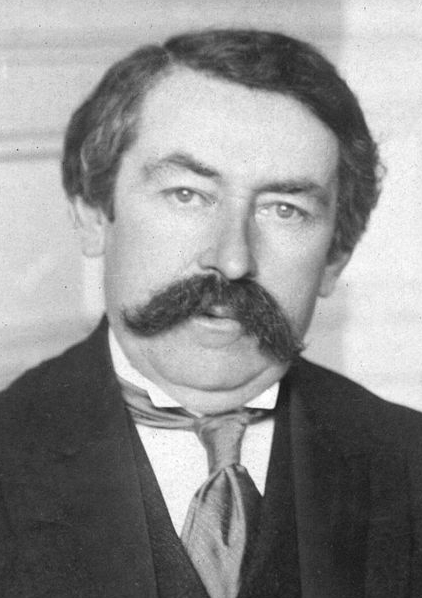

In 1928 American Secretary of State Frank

Kellogg met with French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand and signed a

pact agreeing to renounce war as a means of settling conflicts and to

use peaceful means instead. Soon the Kellogg-Briand Pact was joined by

fifty-nine other nations (including Germany, Italy and Japan) –

seemingly indicating that the world was finally coming to its senses.

Never again would a war such as what the world had gone through ten

years earlier ever have to happen again.

Even Italy’s worshiper of aggressive strength,

Mussolini, pledged his country’s support of the ideal – though it would

not be long before Italian, German, Japanese and other supporters of

Fascism were ridiculing the feebleness of such democratic idealism.

Kellogg

Briand

In any case, the pact did nothing to stop or

even slow down the Fascist aggressions that in the 1930s again moved

the world closer to general war. Rather, it was a dazzling piece of

Utopian Idealism: countries pledging to renounce war as a policy –

except in instances of necessary self-defense (but when in war do

countries not believe that they are fighting in defense of essential

national principles?). Unfortunately, all of this was simply humanistic

illusion, as events would soon prove. Serious conflicts of interest

(such as contested boundaries and revanchist dreams of gathering

nationals scattered in neighboring countries) were never really dealt

with, nor could they be by peaceful means in any case. Too much was at

stake for nation-states not to attempt the use of physical force if

push came to shove. And it soon did.

But in the meantime, those still shocked by the

trauma of the Great War were happy to believe that they had solved

rationally one of life's most critical problems, forever.

|

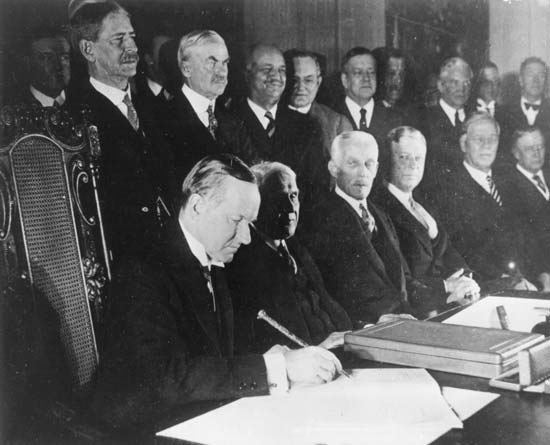

The signing of the Kellogg-Briand pact outlawing

war at the Palais D'Orsay in Paris – August 27,

1928 The signing of the Kellogg-Briand pact outlawing

war at the Palais D'Orsay in Paris – August 27,

1928

U.S.

President Coolidge signing the Kellogg-Briand Pact – January

1929

THE COURT MARTIAL OF GENERAL BILLY MITCHELL (1925) |

|

It is understandable when a people draw a lesson

from a pointless war and thus find themselves very suspicious of

anything that might soon draw them into another. What is not

understandable is when professional military men do not also draw

lessons from a fierce war they have just been through. When an army

General Billy Mitchell himself drew a key lesson from the war, namely

that air power was a major new weapon that needed to be developed by

the U.S. military establishment, he found his urgings ignored. So, he

made his case more demonstrably. n 1921 he had four obsolete

battleships put to sea – and then attacked from the air. The ships were

easily sunk by bombs from his airplanes.

He was told to cease his pressuring of

the military higher ups. But Mitchell was not able to let the matter

simply die quietly – and began to go public with his arguments. By

doing so he courted the wrath of the old guard military. Being

subsequently brought before a court martial, he was found guilty of

undisciplined behavior and suspended from active duty (1925). He

resigned his commission the following year to be able to pursue his air

power crusade undeterred by military protocol.

The effort did indirectly make some

headway eventually when America developed a naval air wing complete

with aircraft carriers and fighter planes able to take off and land on

the decks of these massive ships. This would prove to be a huge factor

later in 1941–1942 when America was attacked by the Japanese. It is

what not only brought America back from the Pearl Harbor disaster but

also delivered a blow to the Japanese navy so stunning (the Battle of

Midway, June 1942) that the Japanese navy was never able to recover

fully.

|

The court-martial of

General Billy Mitchell for his insubordination in pushing for air power

Brown

Brothers

EUROPEAN POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS HEADING THE WORLD IN THE

OPPOSITE DIRECTION |

|

Meanwhile, Europe also struggles to find its way forward

Despite the Idealism of many of the European

leaders, especially those of Great Britain and France, the mood of the

average European was not all that different from the average American,

rural or urban.

For Europeans, who had suffered greatly

through the four years of war, the post-war period was troubled with

the thought that all of the war's high-sounding nationalist spirit had

produced in the end only mindless death and destruction. A spirit of

disillusionment with politicians and cynicism with respect to their

ideas and programs set in, much as it did in America.

This cynical spirit stirred a sense of

political opportunity among a number of extremist political factions

and their leaders: Communists and Social Democrats on the Left and

Fascists on the Right. They found their appeal strongest among the

social classes that had suffered most from the crumbling of the older

social order.

Socialism/Communism.

European soldiers coming out of the war found that with the war over

and war-time industry cutting back, jobs were scarce, and the ones that

did exist paid very poorly. They were deeply resentful of the way their

personal sacrifices were so poorly rewarded – while fat-cat wartime

industrialist owners or capitalists still seemed to be doing fairly

well for themselves. This group of industrial workers was thus easily

manipulated by leaders who urged the workers to rise up against the

wealthy industrial property owners, seize their property and make it

communally their own. This was the basis of the Communist appeal which

produced workers’ uprisings all across Europe in the 1920s (and the

huge Red Scare in early 1920s America).

Fascism.

Other European soldiers, upon a return to their farms, found that they

had been left behind economically and culturally by developments

brought on by the war. With international farm prices running at a new

low, farmers found it difficult to sustain a living for themselves and

their families. They watched with resentment as a fast-growing urban

industrial order appeared to be enjoying many of the new economic

opportunities of the post-war world. This agrarian/ small-townsmen

group was easily manipulated by leaders who stressed the importance of

restoring a largely romanticized traditional agrarian social order.

They promised to bring the glories of a mythical past back to existence

– if the people simply surrendered their hopes and dreams to the total

management by their great leaders. This appeal is the basis for what

will come to be called Fascism.

European Fascism actually had its roots in

Italy when post-war Italy seemed literally to have fallen apart

politically. Although Italy had finally joined the war in 1915 on the

"victorious" side in the Great War, there had been nothing at all about

Italy’s performance in the war to indicate to the average Italian that

they had achieved anything at all of what might be classed as victory.

Instead, coming out of the war, the Italians generally considered their

former leaders as grand failures – which the Italian leaders themselves

understood was their political standing in Italy. Thus they tended to

lay low. And thus also a power vacuum existed in Italy after the war.

And into that vacuum had stepped Benito

Mussolini, the bombastic editor of a Milan newspaper. Mussolini had

started out as a Socialist propagandist – who turned against Socialism

when it refused to support the Italian entry into the Great War.

Mussolini saw the war as a means of bringing Italy to a new strength

and prominence: strength through collective struggle (Fascism).

Mussolini became bitterly opposed to Marxist Socialism, with its call

to European workers to resist taking up arms on behalf of capitalist

war profiteers – a call which Europe’s fiercely nationalist workers had

largely ignored … and then had paid a huge price for their patriotism.

But Mussolini was opposed not only to

Socialist pacifism, he was as opposed to Liberal Idealism with its

hopes to build an international order of peace through a new spirit of

international democratic cooperation. Mussolini accused such

philosophies of peace as merely weakening human strength and producing

effete societies. He exalted strength – strength through conflict,

strength through struggle – which would produce a warlike character

among a people. This in turn would bring them to greatness – greatness

such as the ancient Romans had once exemplified. The key to this

process was achieving an absolute unity of the people through

unswerving loyalty to a great leader, a Duce (Italian simply for

"Leader") such as Mussolini himself proposed to become. He promised

Italians (notably Italy’s industrial leaders) to bring unity to Italy

through a policy of strict enforcement of social conformity through the

use of his street toughs (the Fascist Blackshirts) – who stood ready to

strike total fear in the hearts of labor agitators and anarchists

through whatever means necessary to do so.

At a time when Italy seemed to be

threatened internally by the same forces tearing Russia and Germany

apart, this Fascist call of Mussolini's to enforced unity had a very

strong appeal. Thus it was that in October of 1922 a small group of

Mussolini's Fascists marched on Rome – facing virtually no resistance.

The Italian king responded by asking Mussolini to save the nation by

becoming its leader. Italy now began to head down the path of Fascism –

forced national unity under the domination of the Duce, who was to do

the thinking and direct all the actions of the Italian nation. Any

resistance to his program, actively or even just verbally, was met with

stiff repression.

|

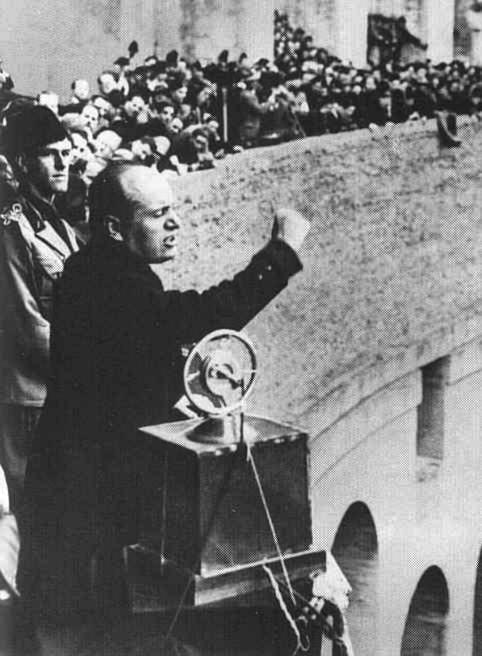

Mussolini marching with Fascists

soon after his October 28, 1922 "March on Rome"

Mussolini marching with Fascists

soon after his October 28, 1922 "March on Rome"

Mussolini greeted by King

Victor Emmanuel III

Mussolini greeted by King

Victor Emmanuel III

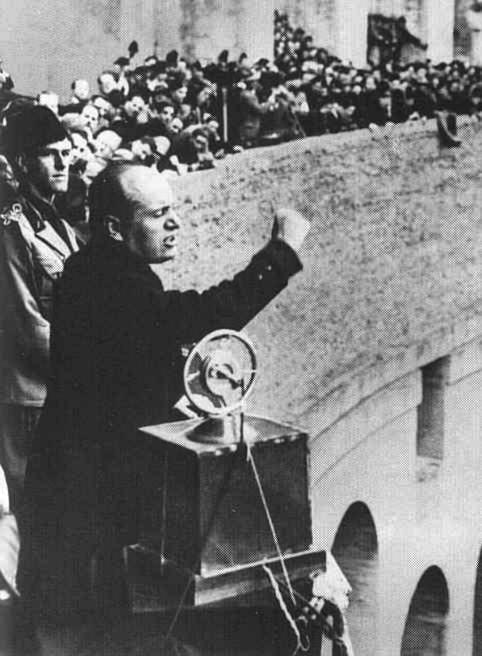

Mussolini at a Fascist

Rally

|

Stalin takes command of Soviet Russia

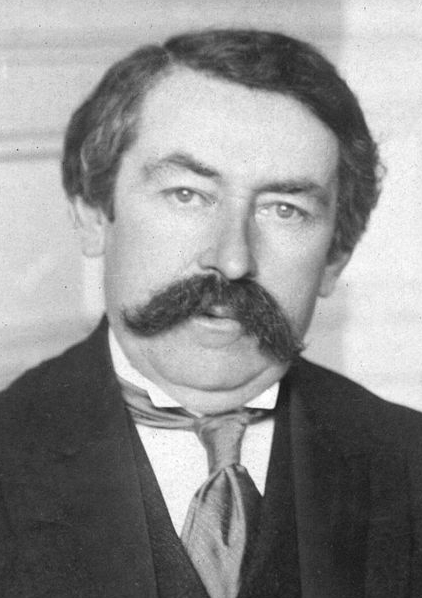

Slowly and painfully the Communist "Red" Army of

Lenin and his close associate Trotsky gained ground against the "White"

Armies of Kerensky and the Tsarists2

– and by 1923 the horrendous Russian civil war was finally over.

Lenin's Bolsheviks or Communists ruled Russia – and much of its former

empire among surrounding non-Russian ethnic groups. But Lenin was a

sick man, and died the following year (1924).

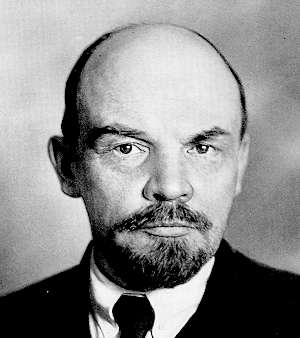

Lenin

Trotsky

Power was supposedly held jointly by the

Bolsheviks serving on the Communist Party's Central Committee – though

most observers supposed that Lenin's closest colleague Trotsky would

emerge as the supreme leader. But Trotsky was more interested in

spreading the Communist revolution to the rest of Europe, treating the

Russian Revolution simply as a staging ground for continuing revolution.

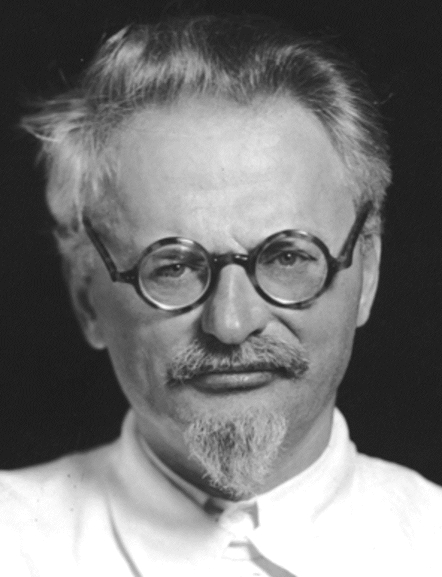

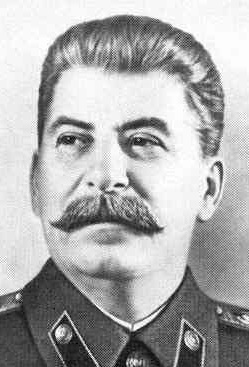

Working behind the scenes was the

mysterious Joseph Stalin, who had been assigned the less glorious task

of overseeing personnel issues (recruitment and promotion of regular

members) at the lower levels of the Party hierarchy. But Stalin had

been using his position to place and promote individuals presumably

loyal to himself personally – thereby building up a personal power base

within the Party, a development that the Bolshevik intellectuals

directing the Party at its highest levels had not been paying much

attention to. Toward the end of the 1920s Stalin was ready to make his

move: he impressed (or intimidated) his fellow Bolsheviks into agreeing

to the need to focus on "revolution in one country" (Russia), to stand

behind his Five-Year Plan for the rapid industrialization of Russia (at

the expense of the Russian countryside and its people), and to oust

Trotsky whose internationalism threatened the security of the

revolution in Russia (or so said Stalin anyway).

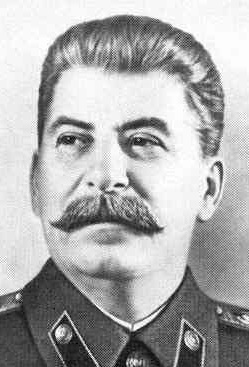

Stalin

With the introduction of his Five-Year

Plan in 1928, Stalin took complete control of the wealth, the

productivity, the very life of the nation – and completely reoriented

its culture to his industrial agenda. Millions of lives would be lost

in this transition, millions more permanently shattered as Stalin

forcibly made the shift of the Russian economy away from agriculture to

heavy industry. Anyone who complained, anyone he even suspected of

complaining, he simply destroyed. There was no way to offer resistance

to Stalin.

And so, the Soviet Russian economy and culture began its move in the new Stalinist direction.

2At

the end of the war, Wilson had sent American soldiers into Russia to

join with other pro-democracy troops (everything from fellow British,

to Czechs and Japanese) in supporting the Whites in the early stages of

that civil war. It was supposedly a most noble effort – in support of

democracy – to intervene in Russia's civil war for such a grand

purpose. Ultimately seeing that this would achieve nothing except to

make the situation worse, Wilson brought the troops home. At least he

got that part right.

Go on to the next section: The Great Stock-Market Crash

Miles

H. Hodges Miles

H. Hodges

| | |

The League of Nations: Wilson's

The League of Nations: Wilson's America's approach to the larger world

America's approach to the larger world The court martial of General Billy

The court martial of General Billy European political developments lead

European political developments lead