1. AMERICA'S COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS

THE VIRGINIA COLONY - Early 1600s

An early English settlement effort at

An early English settlement effort atRoanoke

The Jamestown settlement

The Jamestown settlement

Jamestown's early social dynamics

Jamestown's early social dynamics  The governorship of Sir William Berkeley

The governorship of Sir William Berkeley Bacon's Rebellion (1676)

Bacon's Rebellion (1676)  Southern society takes shape

Southern society takes shapeThe textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 42-52.

AN EARLY ENGLISH SETTLEMENT EFFORT AT ROANOKE |

England Finally Gets in The Game

In the early 1600s it was

finally England's turn to play the game. Much like the young Spanish

conquistadores coming to America a century earlier, young English

aristocratic wannabees, or for that matter anyone seeking social

betterment, looked to America in the hope of finding American gold with

which they could buy land and thus social status. But also English King

James needed money to continue England's struggle against Spain and was

therefore very willing to charter two new colonization efforts to the

New World, to the area at that point known as Virginia.1

One such effort was to be located in the northern part of Virginia

(roughly what was to become New England) and one in the south (focused

on the Chesapeake Bay area of today's Northern Virginia and Southern

Maryland). Two companies were set up in England to oversee these

colonization efforts, one in Plymouth (the northern colony), one in

London (the southern colony).

The first of these ventures (the Plymouth or

northern colony) failed. The second one, planted at Jamestown in 1607,

was more successful - but barely so. But with its success the first

Virginia colony was finally established.

Roanoke - An Earlier, But Failed, Effort at Settlement

Actually, Jamestown was not the first English settlement in America. It

was only the first English settlement to have survived the rigors of

colony planting in the wilds of America. A generation earlier, in the

mid-1580s, a couple of efforts

were made under the sponsorship of Queen Elizabeth's close friend, Sir

Walter Raleigh, to plant a Virginia settlement in a strategic American

coastal position from which the English colonists could search for gold - or simply raid passing Spanish galleons. On a second attempt (1587) a

group of 90 men, 17 women and 11 children was brought to a spot they

named Roanoke, on the Outer Banks of what is today North Carolina. They

were left there to establish an English colony, while the ship returned

to England for more supplies.

The ship was unable to return right away however,

because the English at this point were deeply engaged in this struggle

for their very survival against the mighty Spanish Armada. Not until

the English survived this danger, three years after originally

depositing the settlers in America, was a ship able to send supplies

back to the colony. But upon the ship's arrival, the settlers were

nowhere to be seen - nor was there any indication of where they might

be or what had happened to them.

The news of the Lost Colony put a serious chill on

any further thoughts about another such venture - until another

generation came along at a time when the lure of gold seemed to be

greater than the fear of failure.

1The

name of the corporate venture, "Virginia," was chosen in honor of the

"Virgin Queen" (never married) Elizabeth, who had just given England a

long period of stable rule.

England Finally Gets in The Game

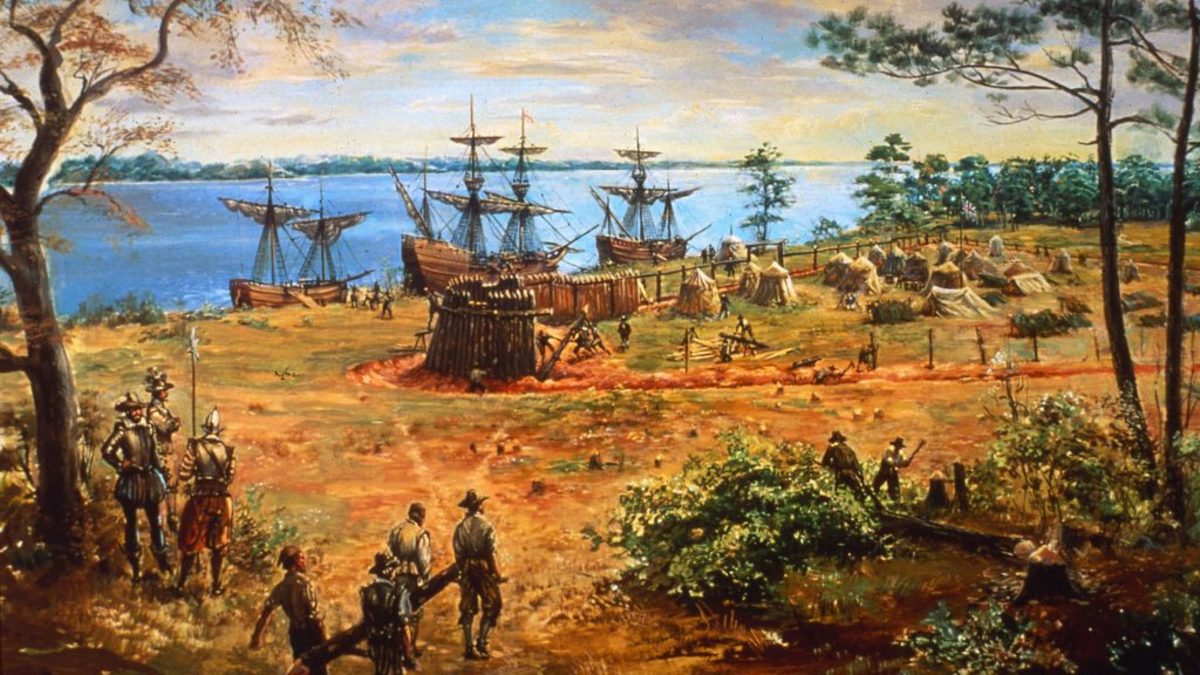

The English at the Roanoke Colony on the Outer Banks

Library of Congress

THE JAMESTOWN SETTLEMENT

James I of England, VI of

Scotland - by John de Critz, c.1606

Dulwich Portrait

Gallery

John Smith

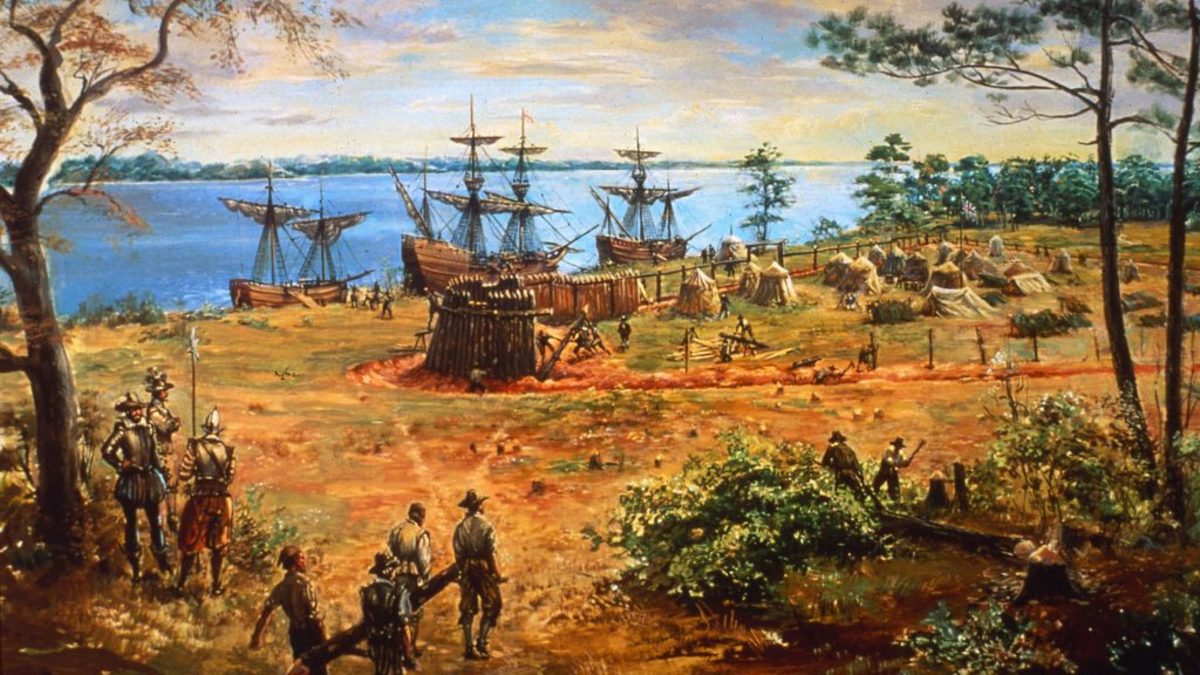

The Early Settlement of Virginia at Jamestown (1607)

With the

support of King James, financial backers or "adventurers" of the

Virginia Company in London were able to amass enough money to outfit

three ships (two of them being incredibly small) to bring some 144 (all

male) settlers to Virginia. Setting out in December of 1606, the

settlers arrived in Virginia a very long five months later in May of

1607. They sailed into the Chesapeake Bay and forty miles up a wide

river, which they named the James River. There they found a small

island which offered good defense against the Spanish - although a very

bad spot for human habitation (swampy, and within a month totally

mosquito-infested). They quickly erected a wooden fort, and named their

new settlement Jamestown.

Seriously lacking among these men was any sense of

how they were to cooperate in order to survive. Beyond the building of

the fort, their interests were strictly personal and greedy. The hunt

to strike it rich in gold began immediately. They were also unprepared

to deal diplomatically with the Powhatan Indians - on whom they would

depend greatly for their survival. They had an appointed Council to

oversee the venture. But the members of the Council found themselves

bitterly at odds with each other from the beginning. Briefly Captain

John Smith brought some order to the group - though he was more

interested in adventure than in group management. He was soon (1609)

forced to return to England after a wound he suffered worsened. He

never returned to the colony. Several times supplies - and new settlers - were brought by the Company to add to the colony. But food was never

ample and the hungry mouths always seemed to outstrip supplies brought

from England.

In general, the colonists themselves refused to

provide for their own food stores - for such manual labor would

automatically disqualify them from the gentry status they so earnestly

sought. A gentleman just did not soil his hands in manual labor!

Thus Jamestown entered a massive starving time

during the winter and spring of 1609-1610 in which 420 of the 480

colonists died of hunger or disease. The 60 survivors decided that it

was time to abandon the settlement. They were ten miles downstream on

the James River headed back toward England when Lord Thomas De La Warr

(Delaware) intercepted them coming from England with a boatload of

supplies and 150 additional settlers - and orders from the king to do

what was necessary to ensure the survival of the colony. The survivors

thus turned back. Jamestown was saved.

John Rolfe

Among the newcomers was the

London businessman, John Rolfe, who on his way to Virginia had picked

up a variety of tobacco seed in Bermuda and who thus began a plantation

in tobacco. The first shipment sent back to England in 1614 proved to

be highly profitable (although the king despised the drug!). Failing to

find gold, many of the colonists soon found that tobacco was not a bad

substitute financially.

Rolfe himself was a significant part of Virginia's

development in more ways than one. His passage to Virginia was itself a

most exceptional one. Leaving England in 1609 along with 500 other

settlers headed for the new world, his ship Sea Venture was hit by a

hurricane and wrecked just off the Bermudas. The ship would be slowly

salvaged over a ten-month period, in which time his wife would give

birth to a child, who would soon die and his wife as well. It was while

he was in Bermuda however that he became familiar with tobacco.

Ultimately, two smaller ships were made from the wreckage of the Sea

Venture, one of which brought him finally to Virginia, in the darkest

days of its struggle for survival. But his interest in tobacco

ultimately helped the colony to survive.

So also did Rolfe's romantic interest in

Pocahontas, beloved daughter of local Indian chief Powhatan. She had

been captured in 1613 in an attempt to have someone of importance to

trade for the release of English being held as prisoners by the

Indians. But she stayed on with the English, quickly learned English

and became a Christian. And in 1614 the governor gave the enraptured

and quite pious Rolfe permission to marry Pocahontas. This actually

served finally to put some degree of peace between the English and the

Indians. But the bliss of it all was not destined to last. In 1616

Rolfe, Pocahontas, and their son Thomas sailed to England, where they

received a royal welcome from the very curious English. Pocahontas

wanted to stay on in England, but they were needed diplomatically back

in Virginia to help hold the peace between the English and the Indians.

But just as they were about to leave, she caught pneumonia and died in

England.

A sad Rolfe returned to Virginia, leaving his son

in the care of English friends. He subsequently married again,

increased his tobacco business substantially, and then died in 1622,

presumably in the Indian uprising of that year (although the exact

causes are not known).

The Jamestown settlers meet with the local Powhatan Indians - 1607

Advertisement for additional English settlers to Virginia - 1609

Thomas West, Lord De La Warr saved Jamestown ... just as the men were

abandoning the colony after the deadly winter of 1609-1610 left

420 of the 480 settlers dead ... by bringing in more supplies and settlers

Tobacco

farmer John Rolfe and Pocahontas marry (1614), helping to settle

relations between the English settlers and the Powhatan Indians

Powhatan Princess Pocahontas (wife of John Rolfe) - dressed as an

English lady

National Portrait Gallery

- Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

|

James I of England, VI of Scotland - by John de Critz, c.1606

Dulwich Portrait Gallery

The Early Settlement of Virginia at Jamestown (1607)

The Early Settlement of Virginia at Jamestown (1607)

With the support of King James, financial backers or "adventurers" of the Virginia Company in London were able to amass enough money to outfit three ships (two of them being incredibly small) to bring some 144 (all male) settlers to Virginia. Setting out in December of 1606, the settlers arrived in Virginia a very long five months later in May of 1607. They sailed into the Chesapeake Bay and forty miles up a wide river, which they named the James River. There they found a small island which offered good defense against the Spanish - although a very bad spot for human habitation (swampy, and within a month totally mosquito-infested). They quickly erected a wooden fort, and named their new settlement Jamestown.

Seriously lacking among these men was any sense of how they were to cooperate in order to survive. Beyond the building of the fort, their interests were strictly personal and greedy. The hunt to strike it rich in gold began immediately. They were also unprepared to deal diplomatically with the Powhatan Indians - on whom they would depend greatly for their survival. They had an appointed Council to oversee the venture. But the members of the Council found themselves bitterly at odds with each other from the beginning. Briefly Captain John Smith brought some order to the group - though he was more interested in adventure than in group management. He was soon (1609) forced to return to England after a wound he suffered worsened. He never returned to the colony. Several times supplies - and new settlers - were brought by the Company to add to the colony. But food was never ample and the hungry mouths always seemed to outstrip supplies brought from England.

In general, the colonists themselves refused to provide for their own food stores - for such manual labor would automatically disqualify them from the gentry status they so earnestly sought. A gentleman just did not soil his hands in manual labor!

Thus Jamestown entered a massive starving time during the winter and spring of 1609-1610 in which 420 of the 480 colonists died of hunger or disease. The 60 survivors decided that it was time to abandon the settlement. They were ten miles downstream on the James River headed back toward England when Lord Thomas De La Warr (Delaware) intercepted them coming from England with a boatload of supplies and 150 additional settlers - and orders from the king to do what was necessary to ensure the survival of the colony. The survivors thus turned back. Jamestown was saved.

Among the newcomers was the London businessman, John Rolfe, who on his way to Virginia had picked up a variety of tobacco seed in Bermuda and who thus began a plantation in tobacco. The first shipment sent back to England in 1614 proved to be highly profitable (although the king despised the drug!). Failing to find gold, many of the colonists soon found that tobacco was not a bad substitute financially.

Rolfe himself was a significant part of Virginia's development in more ways than one. His passage to Virginia was itself a most exceptional one. Leaving England in 1609 along with 500 other settlers headed for the new world, his ship Sea Venture was hit by a hurricane and wrecked just off the Bermudas. The ship would be slowly salvaged over a ten-month period, in which time his wife would give birth to a child, who would soon die and his wife as well. It was while he was in Bermuda however that he became familiar with tobacco. Ultimately, two smaller ships were made from the wreckage of the Sea Venture, one of which brought him finally to Virginia, in the darkest days of its struggle for survival. But his interest in tobacco ultimately helped the colony to survive.

So also did Rolfe's romantic interest in Pocahontas, beloved daughter of local Indian chief Powhatan. She had been captured in 1613 in an attempt to have someone of importance to trade for the release of English being held as prisoners by the Indians. But she stayed on with the English, quickly learned English and became a Christian. And in 1614 the governor gave the enraptured and quite pious Rolfe permission to marry Pocahontas. This actually served finally to put some degree of peace between the English and the Indians. But the bliss of it all was not destined to last. In 1616 Rolfe, Pocahontas, and their son Thomas sailed to England, where they received a royal welcome from the very curious English. Pocahontas wanted to stay on in England, but they were needed diplomatically back in Virginia to help hold the peace between the English and the Indians. But just as they were about to leave, she caught pneumonia and died in England.

A sad Rolfe returned to Virginia, leaving his son in the care of English friends. He subsequently married again, increased his tobacco business substantially, and then died in 1622, presumably in the Indian uprising of that year (although the exact causes are not known).

National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

JAMESTOWN'S EARLY SOCIAL DYNAMICS |

Despite the economic boom that

came to Virginia complements of the tobacco trade, changes were needed

to attract more settlers to the colony. In 1617 the Company ended its

monopoly on land ownership, allowing private ownership. By 1619 there

were ten major plantations in Virginia, mostly along the wide James

River. In that year Virginia received a new governor (Lord Delaware had

died on a return trip to America) and a new colonial assembly. As part

of the plan to encourage settlers to come to Virginia, this legislative

assembly was set up to give the settlers their own voice through two

elected representatives sent to Jamestown from each of the ten

plantations, plus Jamestown itself. Thus in Virginia the idea of

representative democracy was first born in America.

Now the settlers needed land, lots of land - Indian land. In 1622 there was a major

uprising of the Indians led by the new chief Opechancanough (younger

brother of Chief Powhatan), who had planned a surprise massacre of the

inhabitants of the various plantations scattered within what they knew

to be their hunting territory. In a single day 300 to 400 colonists

were killed - although Jamestown itself was spared such destruction

because of a warning issued by an Indian boy to the inhabitants of the

town. Yet the uprising failed to kill but a third of the intruding

English. The surviving English struck back - and the violence continued

for a year until a truce was established. But in fact, the fighting

never really ceased completely.

Troubles

over the high-handed ways of Delaware's deputy, Samuel Argall, created

huge political problems for the colony. Rumors made their way back to

England about the colony's difficulties.

Finally in 1624, because of Indian troubles,

Argall's behavior, and all the rumors which were hurting the

recruitment of settlers, King James suspended the Virginia Company's

charter and reappointed Virginia as a royal colony, directly under his

own governance (or actually under his appointed crown governor).

Virginia was redistricted into counties and towns and the House of

Burgesses' power was reduced somewhat. But the major plantations still

dominated Virginia's local politics (the prestigious Governor's Council

was made up of the heads of the largest plantations).

The

farming of tobacco would prove to be a highly valuable path to wealth -

great wealth - especially for those possessing enough initial capital

to purchase the services of large numbers of indentured servants2

brought in from Europe (and Africa) to work the land for them. The

earliest Virginia planters who purchased the best of the properties

along the shores of Virginia's Tidewater region, where wide navigable

rivers (the James, York, Rappahannock, and Potomac Rivers) allowed

ships from England to pick up their tobacco on docks right at the

river's edge, made excellent profits from the tobacco trade - and thus

were able to purchase the services of additional indentured workers in

order to expand their land holdings and thus overall production. Some

of these plantations consequently became vast in size and operation,

something like great feudal estates of thousands of acres and hundreds

of servants to work those acres. Thus also along the edges of the broad

rivers and numerous bays of Eastern Virginia an English aristocracy

began to grow up in America, dominated by such families as the

Randolphs, the Carters, the Lees, and the Washingtons, whose family

patriarchs typically served on the influential Governor's Council. In

the context of the times this elite-dominated society appeared quite

normal.

But for the other settlers who came later to

Virginia - after the flat, fertile, and directly river-accessible

Tidewater region of Eastern Virginia was basically settled -

opportunities for similar success became quite difficult, if not indeed

even impossible. For the newcomers, life was tough because new land was

available only by pressing into the unsettled Indian woodlands to the

West, involving a dangerous encounter with the Indians. And it took

backbreaking labor in the scorching heat of Virginia to clear a rocky

woodland for tobacco farming. But even with a small cleared farm ready

to produce, a normally servant-less frontier farmer located at some

distance from the ships that would pick up his tobacco found it very

difficult to compete in the tobacco business. He was barely able to eke

out a living in this American land of opportunity. 2Indentured

service was something like an apprenticeship in which, by way of a

contract (the indenture), a young man agreed to work for a master, who

paid for his passage to America and housed and fed him while in his

service. In exchange, the servant was to work in the fields and barns

for the master. At the end of the term of indenture, usually seven

years, the servant was given certain tools and his freedom. And thus

with the training he received during his years of service he was ready

to start off life elsewhere on his own, now himself as a landowner

(usually also as a tobacco farmer) by his own right.

He governed Virginia during the period 1642-1652 and again 1660-1677

In 1642, Virginia received a governor who would play a key role in giving this Virginia society something of a more stable footing, at least for a generation or so. Berkeley was the very bright second son of a family of country gentry, who grew up in England educated by both the rigors of agricultural management and a classical education at Oxford. In 1632 he gained admittance into King Charles's literary circle, the Witts, where Berkeley composed several plays performed before the king. Then in 1639 he took a military command under Charles during the rising conflict in England over the reform of the Church of England, gaining for Berkeley a knighthood. His growing esteem in the eyes of King Charles consequently led to Berkeley's appointment in 1641 as crown governor of Virginia.

But Berkeley was the first royal appointee to take more than a nominal interest in his position as Virginia governor.3 He purchased for himself a section of land (Green Springs) just to the west of the Jamestown capital and began to grow different crops there as a demonstration model of alternatives to tobacco farming. As governor he worked diligently in encouraging other Virginia planters to also diversify their crops.

He clearly became quite supportive politically of the colony as well, and served to enhance the power of the Virginia General Assembly in order for it to be able to act more independently of the royal government in London.

With respect to religion, he was very loyal to Charles's Church of England and quite hostile to those who questioned the Anglican Church and its authority - notably the Puritans, of course. He kept a very close eye on the doctrines and political ideas being preached in Virginia to make sure that they conformed absolutely to the standards of the Church of England. Likewise, he discouraged public education for fear that it would provoke the growth of unwanted ideas and kept a tight rein on what got published, for much the same reason. In general, his strong views supporting the Church of England during a time of rising controversy about the need to purify the Church met with the approval of the Virginians - especially by the prominent Virginia families, who tended to be very supportive of their social identities as proper Anglican Christians.

A major incident occurred in 1644 during Berkeley's first period of service as Virginia Governor (1641-1652): the very savage conflict with the Indians and their leader, Opechancanough, who struck again at the Virginia settlers, killing about 500 of them. But Opechancanough was captured and killed, leaving the Indian uprising leaderless. The Indian attacks continued into the next year, but had run out of energy after Opechancanough's death. Soon the Indians found their power largely broken in Virginia, at least as far west as the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains - which at that point provided the Indians with a more defensible position against the intruding English. In general, Berkeley's handling of the situation met with the approval of the Virginians.

When King Charles was beheaded during the Protestant uprising led by England's Puritan Parliament at the beginning of 1649, thereby bringing England under Parliament's rule as a new Puritan Commonwealth, Berkeley's days as Governor seemed numbered. Still serving as governor in the early days of the rebellion, he offered sanctuary in Virginia to royalists escaping England - until the arrival of Commonwealth authorities in 1652, who removed him from power, but let him continue to reside in Virginia on his Green Springs Plantation.

For the next eight years Virginia was led by Puritan Commonwealth Governors elected by the Virginia General Assembly.

With the restoration in 1660 of the deposed Stuart monarchy (Charles II now being England's new king), Berkeley was also restored to his former position as Virginia governor. But his horizons soon expanded when in the early 1660s he became one of the co-proprietors of the new Carolina colony to the south of Virginia (his older brother John also receiving land in New Jersey).

Perhaps this served to overextend his responsibilities, because in Virginia he was becoming viewed as being increasingly indifferent to some of the problems there, from the poverty experienced by the lower social orders to the troubles with the Indians experienced by the frontier farmers.

3The turnover in Virginia governors was fairly rapid, each governor or acting governor would take his position in Virginia only for a few years at a time, Berkeley being the exception.

BACON'S REBELLION (1676) |

Bacon confronting Berkeley over the lack of protection of the Virginia workers and frontier farmers

Problems also began to develop when in 1675

Berkeley brought onto the Governor's Council a young English

aristocrat, Nathaniel Bacon,4

who came to the Virginia colony to escape a financial scandal back in

England. In the midst of the huge Indian crisis, Bacon asked Berkeley

for permission to use a 400-500 men militia he had assembled to drive

the Indians from the frontier (Bacon actually was aiming at two Indian

groups who had not participated in the attacks, but whose land was

eagerly sought by the Virginia frontiersmen). Berkeley refused. But

Bacon went ahead anyway, bringing the Indians to appeal to Berkeley for

help. Berkeley arrested Bacon, whose men then broke him out of prison.

Bacon subsequently not only went after the Indians, killing and

enslaving many and confiscating their lands, but also issuing a number

of manifestos accusing the governor of corruption and incompetence. In

essence Bacon was striving to make himself Virginia's effective leader.

When Berkeley assembled his own army to go after

Bacon and his militia, a war was on. Meanwhile the King shipped off

from England about 1,000 soldiers to help Berkeley put down the

rebellion. At first, the course of the conflict clearly favored Bacon,

whose militia succeeded in burning Jamestown to the ground in September

of 1676. But a month later, Bacon suddenly died of a fever - and the

rebellion, lacking a leader, quickly collapsed. Berkeley was thus

finally able to restore order just prior to the arrival of the English

troops. Berkeley had twenty-three of the rebels hanged, some without

even the benefit of a trial.

An investigation into the whole affair back in

England brought criticism of both Berkeley and Bacon for their handling

of the matter, especially the treatment of the Indians. Consequently,

Berkeley was removed from his position as governor. Berkeley

immediately sailed to England to protest his dismissal, but died soon

after his arrival. Sadly, he was buried in England, far from the

Virginia countryside that he had given so much of his life to develop. 4He may have also had some family ties to Berkeley's wife, Frances.

The net result of Bacon's rebellion

was a deepening of the social gap between the Virginia aristocracy and

the Virginia frontiersmen. But also, the aristocrats were so unnerved

by the anger of the rebels at this point that the Virginia wealthy lost

interest in indenture - and moved to use fully slave labor in its

place.

In 1619 some 20 Angolan Africans had been seized

from a Portuguese ship (the English privateers were probably hoping to

seize Portuguese gold rather than slaves!) and brought to Virginia.

That number dwindled ... until 1628 when some 100 more slaves were

brought to Virginia. Actually at that time, the slavery of Indians

taken in battle was much more prevalent.

The status of such slaves was at first not

officially different from that of the Whites brought in as indentured

workers. In fact, Africans brought to Virginia were early on classified

as indentured workers, subject to certain service obligations, just

as were the White workers brought in from England, Scotland, Ireland

and Germany. But clearly, arriving as slaves rather than as contracted

workers led to much more rigid terms of service ... some even for a

lifetime, although there were no fixed rules about such matters. Not

yet anyway. Also to be noted was that White slavery existed, though in

only small amounts, as punishment for some kind of crime a person

committed.

Actually, by 1645, a number of freed Africans

(though by no means a very large percentage of Virginia's total African

population) were farming along Virginia's Eastern Shore region.

But as time quickly progressed there was less and

less opportunity for freed workers, Whites or Blacks, who had completed

their required terms of service to now find good land by which they

might prosper. Thus many stayed on with their Virginia masters -

becoming as servants a rather permanent part of the plantation system.

This was especially true of the rather compliant

Africans, who tended to stay on from generation to generation, each new

generation rather permanently indentured. Slowly the Africans were

being locked into the indenture system - legally bound for life in

service to their masters. Also, since indentured services could legally

be bought and sold, soon these African workers and families were looked

on not as humans but as property. Step by step, indenture was

transforming itself into slavery.

Slavery as an institution was recognized as a legal matter only in 1654.5

But as slavery extended its place in the Virginia economy, the laws

regulating and controlling slavery advanced in accompaniment. By 1705

the Virginia Slave Codes defined the institution fairly much as it

would be practiced in Virginia for the next 160 years.

By the very nature of the Virginia plantation system, the lay of the

land, the wideness and depth of the Virginia rivers (such as the James

or York Rivers) in the Tidewater region - the Southern economy remained

essentially rural. Towns were not greatly needed, since the produce of

the major plantations could be loaded directly onto ocean-going ships

bound for England right at the docks in front of the plantation. There

was no need to ship the plantation's produce to some port city or

commercial center to be collected there and then forwarded on to

England. Each plantation conducted its own business with England right

at the plantation. Thus an urban economy did not develop in the South

as it would in the American North.

As for the poor dirt farmers scattered throughout

upland Virginia, their existence was largely one of mere subsistence

farming, their hard work providing barely enough to keep their families

alive. This also made the South unattractive to European immigrants to

America - as they realized that given this wide gap between the rich

aristocrats and the poor dirt farmers in Virginia, they knew exactly in

which class they would eventually find themselves, no matter how hard

they worked. Virginia was not the land of opportunity for an immigrant.

Slave labor and the plantation system that depended on it dictated an

economic reality that worked only to the benefit of the early and

well-established Virginia aristocracy.

Despite this

rather un-Christian social profile of the very rich lording it over the

slaves - and also over the upland poor-White dirt farmers - Virginia

was not Godless. To be sure, there was a Christian character about the

Virginia colony, for that went right along with being English. Much

like in the Catholic Spanish colonies, in Virginia the king's official

Church of England was expected to be established as part of the

(feudal) political order there. However, not until well into the

establishment of the Virginia colony (c. 1620) did some effort take

place to bring Virginia under Anglican church structure, with its

system of parishes presided over by priests or rectors and the

non-clergy vestry. But always there was a shortage of priests willing

to come to America. And even with the creation of the College of

William and Mary in Williamsburg in 16936

(America's second college), there were not many young men willing to

take up the challenge of the Anglican priesthood. Ordination could

occur only in London, as there never was a bishop appointed to the

American colonies during the period prior to American independence in

the 1780s. Also, in status-conscious Virginia, there was little status

and even less economic reward in being an Anglican priest in Virginia.

Also, attendance at Sunday service was the law,

which was seldom enforced - and which thus produced little personal

incentive for the Virginians to be very attentive to the colony's need

for religious discipline.

Virginia did possess some semblance of democracy.

The House of Burgesses continued to give representation to all free

Virginians, although over time the vote was limited to only landowners.

Nonetheless, the greatest power or authority was based on the

Governor's Council, comprised of individuals selected by the Governor

to help him with his governing responsibilities. These individuals were

nearly always drawn from the class of local Virginia aristocrats, the

owners of the major Virginia plantations.

Not surprisingly, Virginians generally were quite

accepting of this political arrangement, holding the social or cultural

understanding that it

was the proper thing to do to defer to one's social betters - just as

things worked back in England. 5Actually,

slavery was practiced widely across the world in the 1600s. The Muslims

specialized in it - and were major slave traders. But Europeans engaged

in the practice as well, though economically it was not particularly

profitable in Europe itself. It really grew big on the islands of the

Caribbean where slaves were brought in in huge numbers to work the

highly profitable sugar cane plantations. Here Africans virtually

replaced the Indian population that had once inhabited the islands. 6It

took 57 years after the Puritans founded Harvard College in New England

to train their Congregational pastors for the Virginia Anglicans to do

the same in founding the College of William and Mary to train their

Episcopal priests.

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges