1. AMERICA'S COLONIAL FOUNDATIONS

PURITAN NEW ENGLAND - Early 1600s

New England's first "Separatist"

New England's first "Separatist"colony: The Plymouth Plantation

(1620s)

John Winthrop – America’s First

John Winthrop – America’s First"Founding Father"

Puritan life

Puritan life  Voices of dissent

Voices of dissent  Relations with the Indians

Relations with the Indians The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work America - The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 52-71.

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

|

|

In the meantime, the English colonization efforts in the area coming to be known as New England were gathering momentum. During the 1620s a number of small companies were formed to settle the area to the north of the Plymouth colony around the Massachusetts Bay. The largest of these, a Puritan settlement at Salem under the leadership of John Endecott, had not fared well: out of the nearly 300 original settlers, over 80 died during the winter of 1628-1629. As a result, only 80 decided to stay on to try to keep the settlement going, and the rest returned to England.

But others were not so easily discouraged. Anyway, life in England was becoming almost impossible. King Charles dismissed Parliament in 1629 and attempted to rule England on his own. The Puritans immediately understood that things were going to get rough for them with the King attempting to rule the country as an absolutist monarch. It was time for the Puritans to leave England.

King Charles in 1629 authorized the creation of the Massachusetts Bay Company, assuming that it was another business venture – not understanding that he was authorizing thousands of Puritans to flee to America to get out from under his increasingly oppressive religious control. In 1629 and 1630, under the direction of the Company's governor, John Winthrop – and financed heavily by Winthrop's own personal fortune – eleven ships containing 1,000 Puritan settlers set off for America, to lands in and around the Boston area. Tragically, 200 of that group died the first winter. But like the Plymouth settlement, that first winter would complete the tragic cost of getting the colony up and running. From then on, the colony prospered greatly (despite the ever-present problem of relations with the Indians).

Winthrop's group of Puritans was merely the beginning of a massive departure of settlers from England to America (but also to Ireland, Canada and the Caribbean). During the next dozen years approximately 20,000 English Puritans migrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, exchanging economic security in England for the risky opportunity to live in America where they could practice their religion without fear of the civil authorities.

Behind all this was more than simply the desire to escape the tyranny of English kings. In coming to America, they could actually build, from the ground up, a society which would function in the ideal Christian way. And they would be able to succeed in this enterprise because they would be doing it in company with God, by a special Covenant between them, God agreeing to be their God, they agreeing to be his people.

This covenant society would be a grand experiment in showing the world how such a relationship with God could work to great human effect. Indeed, by its very existence, this special covenant society would stand as a city upon a hill, offering the light of hope to a darkened world. It was a huge responsibility that God had laid on their shoulders: to live as God himself commanded them to live ... not as sinful man, with all his selfish instincts, might choose to live.

These were not impoverished or status-hungry refugees. The Puritans in general were well educated and had been a quite prosperous group back in England. Their number included a large group of Cambridge University educated pastors – some of the best English intellectual talent of the day.2

Also they had a very strong entrepreneurial instinct and ability to easily take care of themselves. And they naturally brought with them to America their charter, and all of the rights that it guaranteed them. Consequently, they left behind no group in England that the King could pressure or manipulate into religious and political conformity. The Puritans were on their own in America. And very capably so.

The flow of thousands of Puritans to America continued unabated until 1642, when a confrontation between King Charles and the English Parliament developed into a terrible civil war. This then made it extremely difficult for anyone to find the means to get to America from England. At this point the steady flow of settlers to America diminished greatly.

2Indeed,

education was of such importance to these Puritans that once in America

they set themselves to the task of founding their own "Cambridge" in

America: Harvard College, established in 1636 to train additional

clergy that would be needed as the colony expanded.

National Portrait Gallery, London

John Endecott – Governor of the earliest Puritan colony at Salem in Massachusetts

Some of the ships John Winthrop brought to New England, anchored in Boston harbor – 1630 – by William F. Halsall

JOHN

WINTHROP – AMERICA'S FIRST "FOUNDING

FATHER"

John Winthrop – 12 times

governor of Massachusetts

American Antiquarian

Society

Far above all others, John Winthrop was the one who directed the course of

Puritan New England to its success as a grand religious or social

experiment. It was Winthrop's sense of vision, his optimism, that kept

New England on course as it laid out a Godly society built from the

ground up in such a way that it could serve God as a City on a Hill, a

beacon light to all the world. It was Winthrop's background and

personality that helped steer the course of this development between

the dangerous rocks of religious fanaticism on the one hand and

heavy-handed legalism on the other.

Winthrop was nobly born to a father who was both a

lawyer and substantial landowner as well as a director at Trinity

College, Cambridge – which John himself would attend, and there develop

close friendships with other Puritan reformers. At age twenty-six his

father made John Lord of the Manor at Groton and then later a member of

his law firm in London.

John was profoundly religious – his long-developed

journal describing the struggles he had in attempting to live worthily

as a Christian, and his constant appeals to God's grace to give him the

power to live with a spirit of joy, despite the many challenges he

faced in both his private and public life. Those challenges included

the deaths of his first two wives, and the gradual pressure put on the

Puritans by King Charles and his chief advisor, Archbishop Laud.

The latter challenge became particularly

troublesome when in 1629 the king dismissed Parliament – fully

intending to rule England on his own as absolute sovereign – and

dismissed Puritans from public service, including Winthrop, who lost

his position at Court. But this freed up Winthrop to spend his time in

the autumn of 1629 trying to convince the newly formed Massachusetts

Bay Company of the importance of a general emigration of Puritans to

New England. At a Company shareholders' meeting in October the decision

was made to take Winthrop's advice, and, as he was willing himself to

make the journey with the first group of emigrants, he was chosen to

serve as the Company's governor.3

Winthrop then organized the effort to arrange for

a fleet of ships and supplies necessary to carry out this journey to

America. He also was active in recruiting pastors who would be needed

to guide the communities that the Company intended to set up upon

arrival at their new home in America.

Winthrop could be a tough governor, and he made

mistakes, which he freely acknowledged, mistakes which made his heart

all the more supple and which drove him to depend ever more completely

on the mercies of God rather than on his own sense of right-mindedness

to keep things moving forward. He had his detractors, even dedicated

enemies, who felt that his hand was too strong – or not strong enough.

But his love for his fellow New Englanders was immense – as was their

love for him. And it was this love, more than anything else, that gave

the New England experiment its strong foundations.

Establishing a viable community in the New World

meant having to build on new and untested social principles – where

only old English social habits, plus a lot of expectations for a

radically new society, had to be carefully reshaped and redirected so

as to produce something socially viable in the New World. All of this

had to take place in the context of a heated debate raging among

Englishmen about proper or Godly social ideals, and more particularly,

proper or Godly social authority. By tradition the English were very

deferential to the authority of their social "betters," unquestioned

social authority typically being bestowed on those favored by upper

class birth. Thus in one sense it was expected that those of higher

social rank would naturally direct the development of colonial society.

In New England all these social-political ideas

and attitudes would come together in tension. Thus Winthrop (and his

associates) had to carefully guide this new society through these

challenging times in order to develop this new society on firm social

and political ground.

Winthrop addressed this matter from the very

outset by setting an example personally in undertaking hard physical

labor to get housing established for the Puritan settlers in a number

of different settlements in what would become the Boston area. He made

the message very clear: everyone was expected to labor in God's

vineyard. There would be no exceptions, not even for gentry. Hard work

was expected of everyone despite whatever social rank they had back in

England, work that not only served to get the colony established on

solid ground but which also made it clear that there would be no

traditional English social ranking in New England. Here all were equal

by birth in the eyes of God, and thus they would also be equally born

in the eyes of man. The only social rewards to be achieved in New

England would be the product of one's own labor. And even these were to

be kept within a sense of the fundamental equality, and thus unity, of

New England society. That included housing, clothing, and any other

visible markings that back in England were designed to announce clearly

one's status.

An example of how serious Winthrop took this

matter would be the fuss that Winthrop made with his deputy Dudley

because Dudley had built his house with excessive decorative woodwork!

The Larger Legacy of This Puritan Venture

Today the Puritan experiment is treated as if it were some kind of terrible period of religious bigotry in American history.4

Little is taught and therefore little is remembered about those early

formative days except a few unflattering episodes selected from the

long and complex history of the period, episodes that shed little light

on the actual dynamics of the times but instead episodes that point

more to the kinds of social priorities that have emerged in post-modern

America.

On the one hand, the dissenters of those early

years who attacked the moral and political authority of the colony are

today held up as the true heroes of early America. On the other hand,

forgotten are those that labored hard to keep the society united and

moving together against all the forces which threatened to pull that

precious social order apart.

The name John Winthrop is barely known today. This

is very unfortunate for there are great lessons to be learned from how

democracy in America was crafted out of a carefully cultivated spirit

of compromise, one which set careful boundaries to political discourse

so that tempers and egos of the more energetic type might not wreck the

society. Yet it was a system which allowed within those boundaries a

wide latitude of freedom of discussion and debate, something that was

unheard of in those times. Indeed, such a spirit we would be most

unwise not to continue to respect, study, and nurture with the same

care by which it was first developed.

For the blessing of so great a social legacy as

this home-grown American democracy we may thank God – and certainly

also to a very great extent his humble servant John Winthrop, the first

of America's great Founding Fathers.

3Between

his election as the Company's governor in 1629 and his death in 1649,

Winthrop was for 19 of those years elected annually as either the

Company's governor or its deputy governor.

4Very characteristic of how modern America has come to view the entire

Puritan enterprise is the way it is summed up in a very popular

textbook used recently in America's public schools – to teach a rising

generation about its cultural-moral inheritance: Ira Peck and Steven

Deyle's American Adventures: People Making History (New York: Scholastic Inc., 1991).

After seven chapters (uniformly four pages each) three of which are on

the American Indians, one on the Portuguese, one on Columbus, one on

the Spanish Conquistadores, and one on the French, the text arrives at

a four-page coverage of the Jamestown settlement, and then one on New

England, the latter chapter appropriately entitled "They Were Free at

Last." All but three concluding paragraphs of this chapter are focused

on the Pilgrim settlement at Plymouth, with half of that section on the

feast they shared with the Indians.

The only discussion of the Puritans in the entire text of 853 pages is

the three small, very negative paragraphs, describing 1) how the

Puritans came to America seeking the same religious freedom as the

Pilgrims, but were unwilling to extend that same freedom to others, 2)

citing as an example how Roger Williams was banished from the

Massachusetts colony because he thought that Puritans had no right to

impose their beliefs on everyone and 3) how also Anne Hutchinson was

told to leave the colony because Puritan women were required to obey

their husbands and clergy, and she actually held religious gatherings

in her home.

This kind of shaming of the Puritans tells us more about where our

intellectuals find themselves ideologically today, than what history

itself might actually teach us about the dynamic that shaped the birth

and development of the American nation. In any case this is very

typical of how modern teaching wants to depict the very foundational

Puritan legacy.

PURITAN LIFE

Puritan worship – Watertown, Massachusetts

The Early Development of New England

Those that were able to get to Massachusetts during the years of the Great Migration represented some of the best of England's brains and industrial-commercial talent, benefitting Massachusetts greatly and giving it a very special quality as a true homeland, a highly self-sufficient society. Most of the men were skilled as tradesmen of some kind and were dedicated to the task of finding a respectable place for themselves and their families in the larger social scheme of things. (Virginia at that time was still attracting mostly single men hoping simply to get rich enough to eventually return to England in better economic circumstances than they had left it).

There was nothing attractive about New England for those of any aristocratic nature or ambition, for New England offered no known opportunity for striking it rich. Only those who were content to live merely comfortable – yet free – lives were attracted to the colony. This resulted in a high degree of sense of basic equality within the society. Besides, basic Puritan theology stressed how all people were equal in the eyes of God – and anything otherwise was just sinful vanity.

And thus it was that Middle-Class America was born!

Property rights as the foundation of Puritan economic equality

Property ownership was an important consideration in Puritan society (as it was of course also in feudal society), but only as an assurance that the citizen as property-owner would have a stable or conservative interest in the welfare of the society. And property was fairly abundant in New England (at the great cost, of course, to the Indians).

In fact, there was much attention given to the matter of property by the Massachusetts authorities. Each village or town was understood to have just so much property to offer to newcomers, most of it offered on a fairly equitable basis. When that property was fully distributed, a new town (usually west, towards the expanding frontier) would be opened up for settlement and the property there carefully distributed to a new group of settlers. While this offered no one any opportunity for great wealth, it also offered no urban overcrowding and no poverty such as existed widely back in England.

Early New England government

The matter of the government of Massachusetts went through a difficult process of evolution within those same years. At the outset (1630) the colony was under the authority of the Company – which was directed by the Governor and a Council of eight freemen. But under pressure from some of the settlers, the Council expanded membership on a General Court to include 118 of the men, although the Council still continued to conduct most of the colony's business. When a special tax was levied on the colony in 1632 complaints were quick to arise. In 1634 the settlers discovered that the Company's charter actually had provided for the General Court to be made up of all the freemen. But as the colony had become by this time so enormous, that was not a practical possibility. A compromise was reached in the form of representation to the General Court by two members elected by each town – plus the Governor and the members of the Council. The colony now had its own legislature. The General Court not only voted taxes and other matters of general concern of the colony, it took up the responsibility of electing the Governor. It also promulgated a new code of laws, the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) which guaranteed a number of personal rights to, but also the duties of, the colony's citizens. Thus it was that a commercial corporation became a representative democracy of its own design.

The New England Confederation

Two years later (1643) the colonies of Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut and New Haven (excluding Williams' Rhode Island, which did not participate) joined together to form the New England Confederation, primarily to unite their defense efforts against the restless Indians – and also against the expansive French and Dutch. But it also coordinated their jurisdictions so that a person could not avoid the effects of law by simply escaping to another of these colonies. And it provided a mechanism for resolving disputes among the colonies – each colony, regardless of size, possessing two votes each on an issue. Thus even though the civil authorities back in England had made no particular provision for the English colonies to work together, the colonies had taken the initiative on their own to meet this need. This inter-colony cooperation would become an important part of the development of English America.

But that was because they were all very aware of the dangers of not working closely together as a new society. The dangers of failure were a clear and present danger to the colonists. The examples of the failure of efforts to settle the New World were numerous and horrible to behold. And thus the need to work closely together was understood by all.

JOHN

WINTHROP – AMERICA'S FIRST "FOUNDING

FATHER" |

American Antiquarian Society

Winthrop was nobly born to a father who was both a lawyer and substantial landowner as well as a director at Trinity College, Cambridge – which John himself would attend, and there develop close friendships with other Puritan reformers. At age twenty-six his father made John Lord of the Manor at Groton and then later a member of his law firm in London.

John was profoundly religious – his long-developed journal describing the struggles he had in attempting to live worthily as a Christian, and his constant appeals to God's grace to give him the power to live with a spirit of joy, despite the many challenges he faced in both his private and public life. Those challenges included the deaths of his first two wives, and the gradual pressure put on the Puritans by King Charles and his chief advisor, Archbishop Laud.

The latter challenge became particularly troublesome when in 1629 the king dismissed Parliament – fully intending to rule England on his own as absolute sovereign – and dismissed Puritans from public service, including Winthrop, who lost his position at Court. But this freed up Winthrop to spend his time in the autumn of 1629 trying to convince the newly formed Massachusetts Bay Company of the importance of a general emigration of Puritans to New England. At a Company shareholders' meeting in October the decision was made to take Winthrop's advice, and, as he was willing himself to make the journey with the first group of emigrants, he was chosen to serve as the Company's governor.3

Winthrop then organized the effort to arrange for a fleet of ships and supplies necessary to carry out this journey to America. He also was active in recruiting pastors who would be needed to guide the communities that the Company intended to set up upon arrival at their new home in America.

Winthrop could be a tough governor, and he made mistakes, which he freely acknowledged, mistakes which made his heart all the more supple and which drove him to depend ever more completely on the mercies of God rather than on his own sense of right-mindedness to keep things moving forward. He had his detractors, even dedicated enemies, who felt that his hand was too strong – or not strong enough. But his love for his fellow New Englanders was immense – as was their love for him. And it was this love, more than anything else, that gave the New England experiment its strong foundations.

Establishing a viable community in the New World meant having to build on new and untested social principles – where only old English social habits, plus a lot of expectations for a radically new society, had to be carefully reshaped and redirected so as to produce something socially viable in the New World. All of this had to take place in the context of a heated debate raging among Englishmen about proper or Godly social ideals, and more particularly, proper or Godly social authority. By tradition the English were very deferential to the authority of their social "betters," unquestioned social authority typically being bestowed on those favored by upper class birth. Thus in one sense it was expected that those of higher social rank would naturally direct the development of colonial society.

In New England all these social-political ideas and attitudes would come together in tension. Thus Winthrop (and his associates) had to carefully guide this new society through these challenging times in order to develop this new society on firm social and political ground.

Winthrop addressed this matter from the very outset by setting an example personally in undertaking hard physical labor to get housing established for the Puritan settlers in a number of different settlements in what would become the Boston area. He made the message very clear: everyone was expected to labor in God's vineyard. There would be no exceptions, not even for gentry. Hard work was expected of everyone despite whatever social rank they had back in England, work that not only served to get the colony established on solid ground but which also made it clear that there would be no traditional English social ranking in New England. Here all were equal by birth in the eyes of God, and thus they would also be equally born in the eyes of man. The only social rewards to be achieved in New England would be the product of one's own labor. And even these were to be kept within a sense of the fundamental equality, and thus unity, of New England society. That included housing, clothing, and any other visible markings that back in England were designed to announce clearly one's status.

An example of how serious Winthrop took this matter would be the fuss that Winthrop made with his deputy Dudley because Dudley had built his house with excessive decorative woodwork!

Today the Puritan experiment is treated as if it were some kind of terrible period of religious bigotry in American history.4 Little is taught and therefore little is remembered about those early formative days except a few unflattering episodes selected from the long and complex history of the period, episodes that shed little light on the actual dynamics of the times but instead episodes that point more to the kinds of social priorities that have emerged in post-modern America.

On the one hand, the dissenters of those early years who attacked the moral and political authority of the colony are today held up as the true heroes of early America. On the other hand, forgotten are those that labored hard to keep the society united and moving together against all the forces which threatened to pull that precious social order apart.

The name John Winthrop is barely known today. This is very unfortunate for there are great lessons to be learned from how democracy in America was crafted out of a carefully cultivated spirit of compromise, one which set careful boundaries to political discourse so that tempers and egos of the more energetic type might not wreck the society. Yet it was a system which allowed within those boundaries a wide latitude of freedom of discussion and debate, something that was unheard of in those times. Indeed, such a spirit we would be most unwise not to continue to respect, study, and nurture with the same care by which it was first developed.

For the blessing of so great a social legacy as this home-grown American democracy we may thank God – and certainly also to a very great extent his humble servant John Winthrop, the first of America's great Founding Fathers.

3Between his election as the Company's governor in 1629 and his death in 1649, Winthrop was for 19 of those years elected annually as either the Company's governor or its deputy governor.

4Very characteristic of how modern America has come to view the entire Puritan enterprise is the way it is summed up in a very popular textbook used recently in America's public schools – to teach a rising generation about its cultural-moral inheritance: Ira Peck and Steven Deyle's American Adventures: People Making History (New York: Scholastic Inc., 1991).

After seven chapters (uniformly four pages each) three of which are on

the American Indians, one on the Portuguese, one on Columbus, one on

the Spanish Conquistadores, and one on the French, the text arrives at

a four-page coverage of the Jamestown settlement, and then one on New

England, the latter chapter appropriately entitled "They Were Free at

Last." All but three concluding paragraphs of this chapter are focused

on the Pilgrim settlement at Plymouth, with half of that section on the

feast they shared with the Indians.

The only discussion of the Puritans in the entire text of 853 pages is

the three small, very negative paragraphs, describing 1) how the

Puritans came to America seeking the same religious freedom as the

Pilgrims, but were unwilling to extend that same freedom to others, 2)

citing as an example how Roger Williams was banished from the

Massachusetts colony because he thought that Puritans had no right to

impose their beliefs on everyone and 3) how also Anne Hutchinson was

told to leave the colony because Puritan women were required to obey

their husbands and clergy, and she actually held religious gatherings

in her home.

This kind of shaming of the Puritans tells us more about where our

intellectuals find themselves ideologically today, than what history

itself might actually teach us about the dynamic that shaped the birth

and development of the American nation. In any case this is very

typical of how modern teaching wants to depict the very foundational

Puritan legacy.

PURITAN LIFE

Puritan worship – Watertown, Massachusetts

The Early Development of New England

Those that were able to get to Massachusetts during the years of the Great Migration represented some of the best of England's brains and industrial-commercial talent, benefitting Massachusetts greatly and giving it a very special quality as a true homeland, a highly self-sufficient society. Most of the men were skilled as tradesmen of some kind and were dedicated to the task of finding a respectable place for themselves and their families in the larger social scheme of things. (Virginia at that time was still attracting mostly single men hoping simply to get rich enough to eventually return to England in better economic circumstances than they had left it).

There was nothing attractive about New England for those of any aristocratic nature or ambition, for New England offered no known opportunity for striking it rich. Only those who were content to live merely comfortable – yet free – lives were attracted to the colony. This resulted in a high degree of sense of basic equality within the society. Besides, basic Puritan theology stressed how all people were equal in the eyes of God – and anything otherwise was just sinful vanity.

And thus it was that Middle-Class America was born!

Property rights as the foundation of Puritan economic equality

Property ownership was an important consideration in Puritan society (as it was of course also in feudal society), but only as an assurance that the citizen as property-owner would have a stable or conservative interest in the welfare of the society. And property was fairly abundant in New England (at the great cost, of course, to the Indians).

In fact, there was much attention given to the matter of property by the Massachusetts authorities. Each village or town was understood to have just so much property to offer to newcomers, most of it offered on a fairly equitable basis. When that property was fully distributed, a new town (usually west, towards the expanding frontier) would be opened up for settlement and the property there carefully distributed to a new group of settlers. While this offered no one any opportunity for great wealth, it also offered no urban overcrowding and no poverty such as existed widely back in England.

Early New England government

The matter of the government of Massachusetts went through a difficult process of evolution within those same years. At the outset (1630) the colony was under the authority of the Company – which was directed by the Governor and a Council of eight freemen. But under pressure from some of the settlers, the Council expanded membership on a General Court to include 118 of the men, although the Council still continued to conduct most of the colony's business. When a special tax was levied on the colony in 1632 complaints were quick to arise. In 1634 the settlers discovered that the Company's charter actually had provided for the General Court to be made up of all the freemen. But as the colony had become by this time so enormous, that was not a practical possibility. A compromise was reached in the form of representation to the General Court by two members elected by each town – plus the Governor and the members of the Council. The colony now had its own legislature. The General Court not only voted taxes and other matters of general concern of the colony, it took up the responsibility of electing the Governor. It also promulgated a new code of laws, the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) which guaranteed a number of personal rights to, but also the duties of, the colony's citizens. Thus it was that a commercial corporation became a representative democracy of its own design.

The New England Confederation

Two years later (1643) the colonies of Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut and New Haven (excluding Williams' Rhode Island, which did not participate) joined together to form the New England Confederation, primarily to unite their defense efforts against the restless Indians – and also against the expansive French and Dutch. But it also coordinated their jurisdictions so that a person could not avoid the effects of law by simply escaping to another of these colonies. And it provided a mechanism for resolving disputes among the colonies – each colony, regardless of size, possessing two votes each on an issue. Thus even though the civil authorities back in England had made no particular provision for the English colonies to work together, the colonies had taken the initiative on their own to meet this need. This inter-colony cooperation would become an important part of the development of English America.

But that was because they were all very aware of the dangers of not working closely together as a new society. The dangers of failure were a clear and present danger to the colonists. The examples of the failure of efforts to settle the New World were numerous and horrible to behold. And thus the need to work closely together was understood by all.

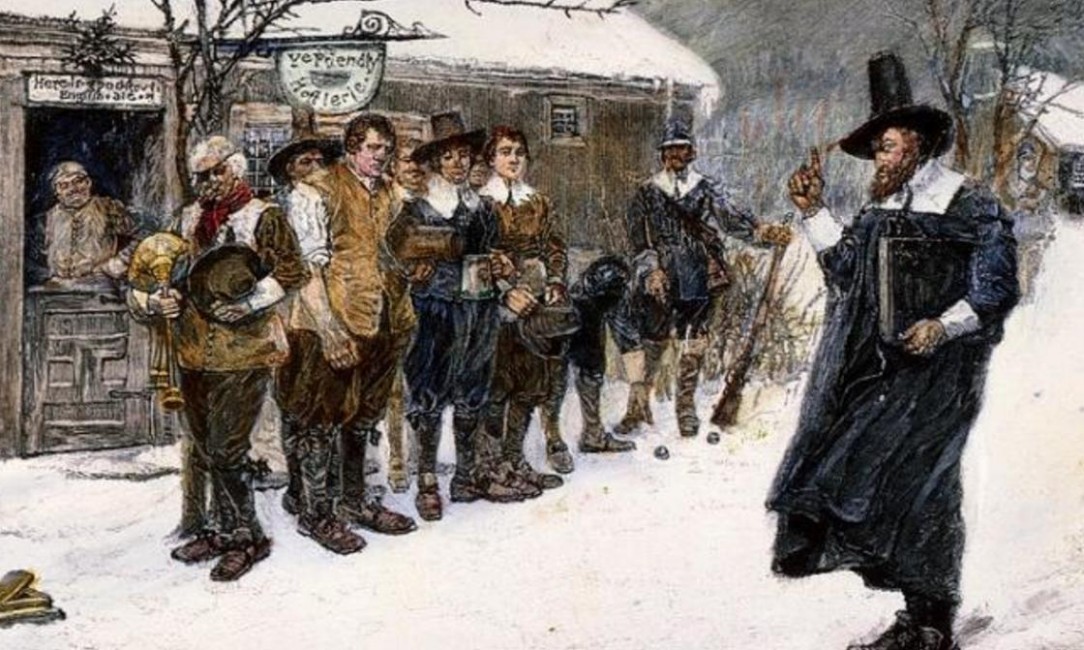

|

To the surprise of moderns, the Puritans enjoyed their beer (water was not reliably a healthy drink at the time)

Life in Boston - 1660s

VOICES

OF DISSENT |

Roger Williams - arrived at Massachusetts and assigned several pulpits, but could never find the purity he sought in the colony and was thus forced to start up his own "Providence" colony in 1635-1636

One of these dissenters was Roger Williams, a supremely intelligent and

personable young man, who came to the colony in 1631 and was

immediately offered the pulpit of the Boston church. But he was a

compulsive perfectionist, unable to locate the perfection he always

hungered for, thus finding himself to be a tormented soul under the

control of personal instincts that made him an early version of the

self-destructive Humanist (in other words, an individual unable to

accept the fact that realistically the world will always be full of

sinners, no matter how hard you try to rewrite the rules of life). Thus

he declined the Boston pulpit because he felt the church not to be

pure enough (it included members who had participated in a Church of

England communion service and had failed to repent of this great sin).

He accepted the pulpit in Plymouth, but eventually found the church

there also not pure enough. He switched to the pulpit in Salem, and

from there began a wider quest for purity within the larger

Massachusetts colony, particularly over the matter of the very right of

the colony to exist at all. His major concern, one that he harped on

most loudly, was about the illegitimacy of the charter that authorized

the Massachusetts Company to be about its business in America. The

charter had come from the English king, not the Indians, the only ones

who, according to Williams, had the right to issue such permission.

His criticisms soon started fraying the nerves of the colony's leaders, who tried to get him to understand how harmful to the spirit of unity of the community his attacks were becoming. Being reprimanded by the Council for his trouble-making, he quieted down for a while. But then he soon started back up again. His attacks on the colony for having received their grant from the king without the assent of the local Indians the Council knew would prove highly offensive to the king should he get wind of Williams' tirades. The whole venture could be compromised by Williams' attacks. He was called a second time (summer of 1635) before the Council for his trouble-making. An impasse developed between the Council and Williams: banishment was finally ordered (October) – but postponed because of the arrival of winter, provided that he stopped his attacks on the colony's authorities ... which he seemed unable to do. Thus about to be expelled, he and a group of followers left the colony (January 1636), taking refuge among the Wampanoag Indians. In the spring, having purchased land from the Narragansett Indians, he founded his Providence Colony (in the future Rhode Island) where he could put his purer social ideas into play.

In accordance with his own fundamental principles, he opened up his colony to full (male) political participation by anyone, regardless of particular religious persuasion. Thus Anabaptists (Baptists) joined his colony. These he joined, for a few months anyway ... until he found problems with this group of Baptists as well. Then to find refuge in Williams' colony came the hyper-activist Quakers,5 whose most unusual theological ideas and behavior were highly contradictory to the fundamental principles of the Bay colony. Williams personally disliked (and debated) Quaker theology. But he nonetheless permitted them to stay. However his colony also became a natural attraction for all the ruffians and malcontents who found the discipline of the Bay Colony not to their liking. Ironically, these newcomers who would soon have the opportunity to quote some of Williams' own earlier sermons, enjoyed denouncing him as a hypocrite when he himself attempted to force some kind of social discipline on his colony!

And oddly enough, several years later he returned

to England to get a charter from Parliament authorizing his new

colony of Providence, the very thing that he had been loudest about in

his critique of the Bay Colony's legitimacy!

5The

more typical image held of the Quakers today is their quiet manner and

spiritual gentleness. But in their early stages of existence (the

mid–1600s) they were loud, abrasive, even lewd in their rather violent

demonstrations against Puritan piety. The quietist image will not

develop until much later.

a painting by Alonzo Chappel - 1858

Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design

Anne Hutchinson stands in judgment before the Boston elders - 1638. She was claiming that God had revealed to her that all the pastors, except her beloved pastor John Cotton, served the anti-Christ.

Another of these famous free spirits that the moderns love so much to extol was Anne Hutchinson. She and her husband came to New England in 1634 and she immediately gravitated to the Boston pastor John Cotton, whom she had taken a liking to back when he was a pastor in England. She flattered her way into importance in his eyes – and soon the eyes of others in his church. She gathered a group in her home to discuss his sermons,6 extolling his great virtues in comparison to other pastors, whom she insisted were less worthy of their calls. Soon she was passing judgment on all the leaders of the community, claiming that only Cotton preached a covenant of grace, the rest a covenant of works. Further, she began to claim that she possessed this power of judgment because it was given her by God. She was now posing herself as some kind of prophet, enlightened with spiritual insights permitting her to see into the ministry of others. Eventually she concluded that none of the pastors in the colony (except Cotton) were truly fit to preach the gospel.

Thus she found herself – under divine authority, of course – slandering the community's leaders, gathering a rather large party or group increasingly hostile to those leaders – and in general threatening the harmony of the community. This was more than simply exercising free speech. She was therefore called before the Council (1638).

Much is made by feminists today that she was under indictment simply because she was a woman daring to challenge the male authorities of the Colony. But let the concluding portion of the trial speak for itself:

Mr. Winthrop, Governor. Let us state the case and then we may know what to do. That which is laid to Mrs. Hutchinson's charge is this, that she hath traduced the magistrates and ministers of this jurisdiction, that she hath said the ministers preached a covenant of works and Mr. Cotton a covenant of grace, and that they were not able ministers of the gospel, and she excuses it that she made it a private conference and with a promise of secrecy, ?c. now this is charged upon her, and they therefore sent for her seeing she made it her table talk, and then she said the fear of man was a snare and therefore she would not be affeared of them. ...Mrs. Hutchinson. If you please to give me leave I shall give you the ground of what I know to be true. Being much troubled to see the falseness of the constitution of the church of England, I had like to have turned separatist; whereupon I kept a day of solemn humiliation and pondering of the thing; this scripture was brought unto me – he that denies Jesus Christ to be come in the flesh is antichrist – This I considered of and in considering found that the papists did not deny him to be come in the flesh nor we did not deny him – who then was antichrist? . . . The Lord knows that I could not open scripture; he must by his prophetical office open it unto me. . . . I bless the Lord, he hath let me see which was the clear ministry and which the wrong. Since that time I confess I have been more choice and he hath let me to distinguish between the voice of my beloved and the voice of Moses, the voice of John Baptist and the voice of antichrist, for all those voices are spoken of in scripture. Now if you do condemn me for speaking what in my conscience I know to be truth I must commit myself unto the Lord.

Mr. Nowell. How do you know that that was the spirit?

Mrs. H. How did Abraham know that it was God that bid him offer his son, being a breach of the sixth commandment?

Mr. Dudley, Deputy Governor. By an immediate voice.

Mrs. H. So to me by an immediate revelation.

Dep. Gov. How! an immediate revelation.

Mrs. H. By the voice of his own spirit to my soul. I will give you another scripture, Jer. 46. 27, 28 out of which the Lord shewed me what he would do for me and the rest of his servants. – But after he was pleased to reveal himself to me . . . Therefore I desire you to look to it, for you see this scripture fulfilled this day and therefore I desire you that as you tender the Lord and the church and commonwealth to consider and look what you do. You have power over my body but the Lord Jesus hath power over my body and soul, and assure yourselves thus much, you do as much as in you lies to put the Lord Jesus Christ from you, and if you go on in this course you begin you will bring a curse upon you and your posterity, and the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. . . .

Gov. The court hath already declared themselves satisfied concerning the things you hear, and concerning the troublesomeness of her spirit and the danger of her course amongst us, which is not to be suffered. Therefore if it be the mind of the court that Mrs. Hutchinson for these things that appear before us is unfit for our society, and if it be the mind of the court that she shall be banished out of our liberties and imprisoned till she be sent away, let them hold up their hands. . . .

Gov. Mrs. Hutchinson, the sentence of the court you hear is that you are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society, and are to be imprisoned till the court shall send you away.

Mrs. H. I desire to know wherefore I am banished?

Gov. Say no more, the court knows wherefore and is satisfied.

6Actually holding such discussion in her home was not an uncommon thing among Puritan women, who were actually quite active in forming and leading prayer and discussion groups, ones involving men as well as women. See: Mark A. Noll, A History of Christianity in The United States and Canada (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1992), pp. 60-61.

Hooker was another individual who departed from the colony because of

disagreements he had with its authorities over key issues. But his

departure was deeply mourned

by those authorities, for they considered him one of their very best

leaders. Nonetheless they granted him his request to depart, seeing it

as God's way of extending the Puritan domain.

Hooker's

departure from Massachusetts was deeply regretted by the Massachusetts

leaders. But Hooker held deep feelings that church authority and

civil authority should be separate items ... and moved on to set up his

own colony amidst a number of other new and growing

Puritan colonies in Connecticut.

Hooker was undoubtedly the most highly respected

and beloved Puritan pastor back in England ... and the most detested by

the king and bishops. He was forced to flee the country in 1630, make

his way to Holland, and then three years later join his fellow Puritans

in Massachusetts. He was immediately given the pulpit in Newe Towne

(Cambridge) and became a key voice in the life of the Colony.

But he too was bothered by the way religion and

politics were bound so closely together in Massachusetts. The colony's

officers, both civil and religious (governors, magistrates, pastors,

teachers, etc.), were elected only by full members of the Church.

Hooker felt strongly however that the elections of civil officers

should be open to all citizens, or at least property-holders among

them, regardless of their status within the Church. He felt so strongly

about this issue – and the Massachusetts officers felt so strongly

opposed to his idea – that in 1636 he petitioned the Council and was

granted permission to leave the Colony with 100 of his church members

to establish a new settlement to the West, at Hartford on the

Connecticut River. Here he joined other English settlements at Windsor

and Wethersfield, established only a few years earlier along the

Connecticut River. In 1637 they combined to fight the Pequot war and in

1639 even formed a joint government, defined in the Fundamental Orders

of Connecticut, largely in line with Hooker's philosophy on civil and

religious authorities.

His influence remained strong however not just in

Connecticut but throughout New England. He continued to be very close

to both Winthrop in Massachusetts and Williams in Rhode Island,

traveled frequently to Boston and to Providence for consultations, and

helped create the notion that despite the doctrinal differences among

these leaders, they were still closely united in their vision of

creating a New Israel in America.

In addition to these social and theological issues

there were a number of economic issues also at work in the development

of the Connecticut colony. The land around Boston was stony and

ill-suited for farming. And the population was growing rapidly in the

Bay Colony, putting tremendous pressure on the land's ability to

support community life. But the land along the Connecticut River was

fertile and productive. Thus many Puritans began pouring into the area

simply to take advantage of the better soil.

And nearby another colony, New Haven, was set up

in 1638 by Puritans who began to feel that Winthrop's Bay Colony was

not strict enough in enforcing its Calvinist ideals.

RELATIONS WITH THE INDIANS |

The Pequot War

Endecott (not only former governor in the early days of the Puritan settlement at Salem but also former soldier), angry over a local murder by some Indians, led a raiding party against the Pequot, who in turn took revenge. This quickly spiraled into massacres of both English and Indian settlements. The worst was the near total slaughter of the Pequot (600 or 700?) at their village at Mystic by a force of English and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies. This attack and several others like it (though of a smaller nature) broke the power of the Pequot. Some of the surviving Pequot escaped to neighboring lands (the Mohawk, however, turned them over to the English as a show of friendship). But most were given to the Narragansetts and Mohegans as slaves or sold as slaves to Bermuda or the West Indies, or even sold to Puritan families in Massachusetts and Connecticut as household slaves. And Pequot land was confiscated by the English. The Pequot were devastated.

John Eliot, as minister/teaching elder, was one of the early leaders of the colony (arrived in 1631). He co-edited the Bay Psalm Book

(the first book published in the English colonies) in 1640 and set up

the Roxbury Latin School in 1645. But his most notable achievement was

his missionary work with the Massachusetts Indians. In 1646 the General

Court authorized support for a Christian mission to the Indians, and

Eliot took the lead in the effort, giving the first sermon that year in

the Natick language. His work drew interest back in England and in 1649

the heavily Puritan Long Parliament subscribed 12,000 pounds (silver

coinage) toward the mission. He eventually completed a translation of

the Bible in the Natick language (1663) and created an Indian grammar

book (1666). He also organized the newly converted Indians, called

"Praying Indians," into communities along the English frontier (fourteen

eventually), the foremost at Natick. But these Indian communities

served a political purpose as well, for they acted as a buffer between

the English and the more hostile Indians.

When however a major English-Indian war finally

erupted (1675) the English lost their trust in these Indian allies and

confined or resettled them, thus ending the separate status of the

Praying Indians.

Huntington Library

Eliot not only wrote the first book printed in English America, The Bay Psalm Book, he translated the Bible into the Indian Natick language.

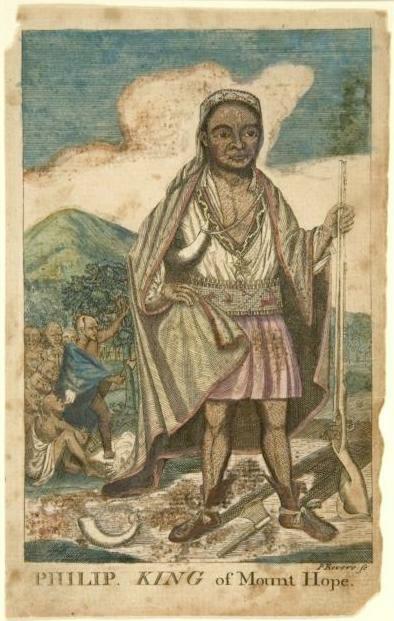

The situation was thus already very tense when Metacom began to plot this act of Indian reprisal against the English everywhere. The war erupted in gradually growing stages starting with the murder in 1675 of a Praying Indian who had warned the English of Metacom's plans to attack the English settlements. His Indian murderers were captured, tried and hanged – leading to a countering attack on an English settlement by a group of Indians. The violence now escalated quickly. The Indian attacks against various English settlements gathered momentum during the summer and early fall of 1675. In the early winter the colonist militias struck back furiously at the Narragansetts, who had been sheltering Wampanoags.

Little by little Metacom and his warriors began to lose ground. They had also missed the growing season that they would need to survive the coming winter and they knew that their situation was growing desperate. Warriors began to drift away from Metacom – especially as the English offered amnesty to Indians who would give up the fight (important because continued fighting was resulting in whole Indian units being surrounded and slaughtered, men, women and children). Metacom now had become a man on the run. In August he was finally tracked down and killed by an Indian who was a member of one of the search parties looking for him. Quickly the whole Indian uprising fizzled out.

Miles

H. Hodges

Miles

H. Hodges