| American

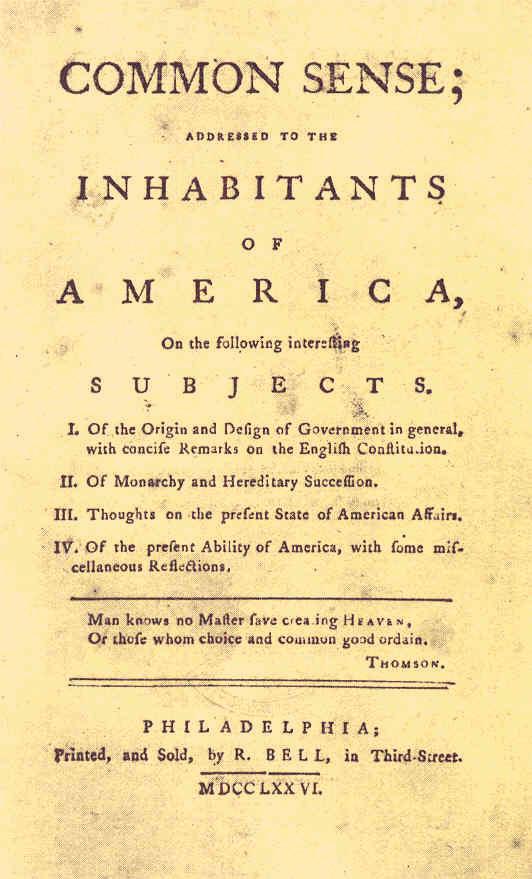

spirits were not dampened. In early 1776, Thomas Paine wrote a

pamphlet, Common Sense, daring to speak the unspeakable: it was time

for Americans to separate from England and establish their own

government. In Paine's opinion, a republic was the best type of

government for America. The pamphlet was widely read and agreed with by

many. It was time to leave the British Empire.

But such action would require the decision of the

Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Yet none of the delegates had

come to Philadelphia with this idea in mind or with any specific

instructions on this matter from the colonial assemblies they were

representing. They would have to return to their colonies and secure

authorization. Of course this would be hotly contested by many who,

though highly irritated at the high-handedness of the authorities in

London, were yet quite unwilling to break the link with the Mother

country.

The debate in America in the spring of 1776 was

intense, although clearly there was a growing momentum in the colonies

in support of independence. Starting with North Carolina, one by one

some of the colonial assemblies passed resolutions authorizing their

delegates to vote for formal independence from England. But action

stalled in the middle colonies. When in mid-May Congress took up a

Declaration of Independence written by John Adams, four of the middle

colonies voted against it. The Maryland delegation even walked out.

But the independence momentum was gathering

strength. On the same day that Congress passed the less than unanimous

Adams declaration, the Virginia Assembly voted strongly for

independence. Thus politically armed, the Virginia delegation arrived

in Philadelphia in early June and submitted its own independence

resolution for a vote:

Resolved, that these

United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent

States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British

Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of

Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

The debate that followed was intense. But one by

one – with the exception of New York, whose colonial assembly was sent

scattering by the British occupation before the Assembly had a chance

to vote – the colonial assemblies were instructed to vote for

independence.

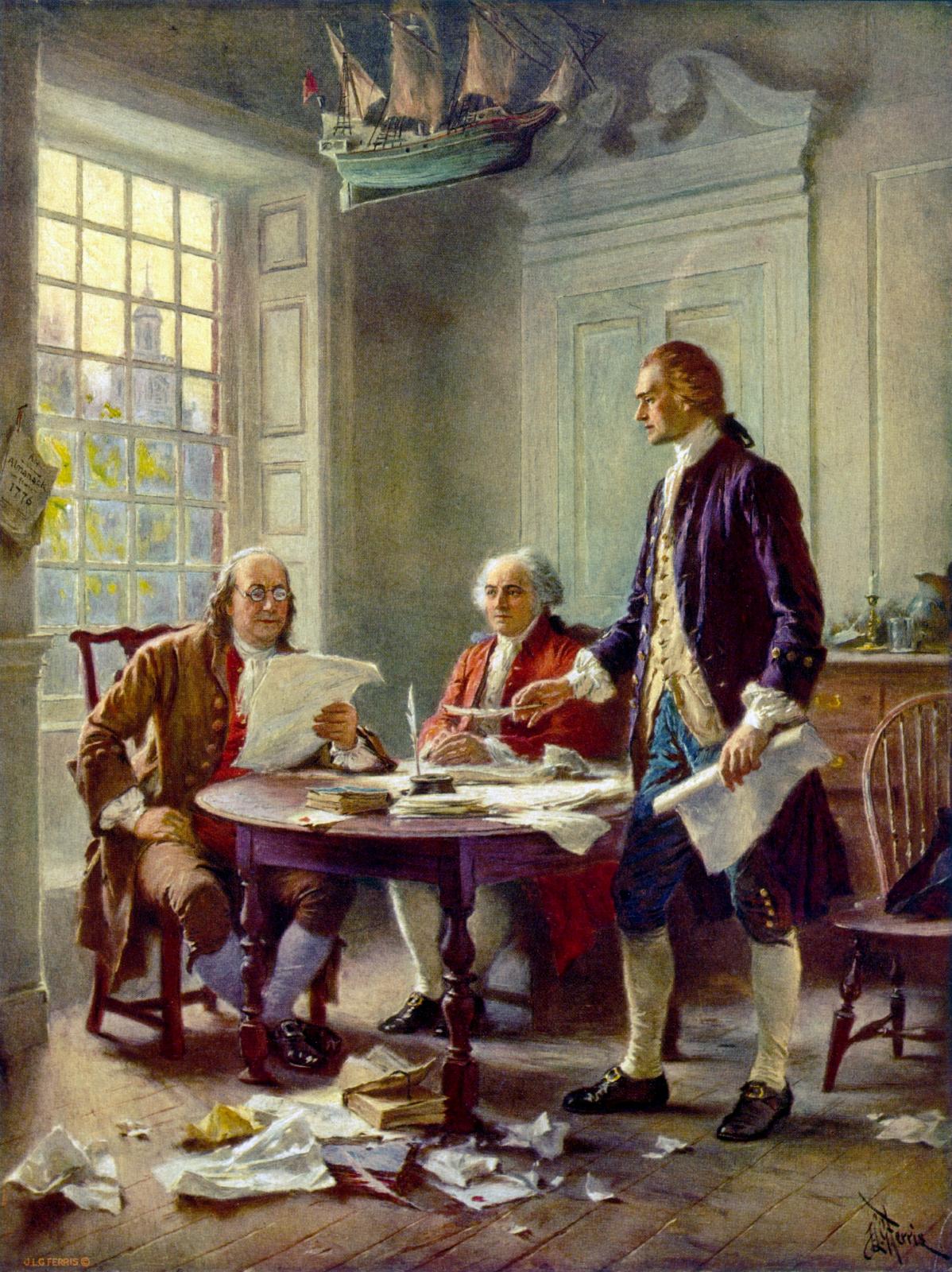

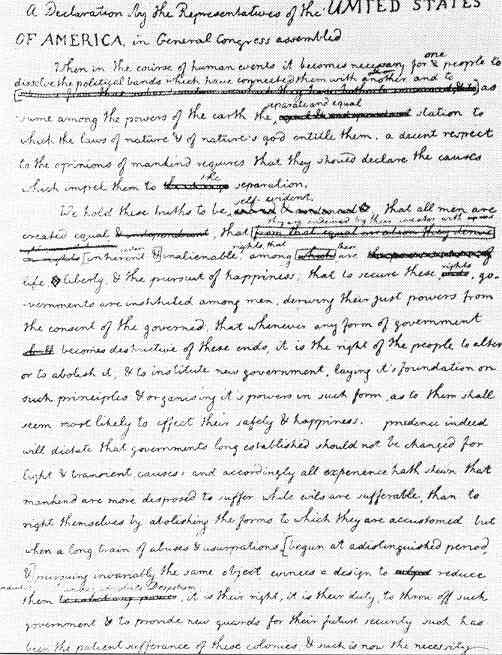

Thus a committee of five was appointed to draft an

explanation justifying the move to independence, to be submitted to the

Continental Congress along with the resolution. Ultimately the task of

drafting such a statement was given to the young, scholarly Virginia

aristocrat, Thomas Jefferson. He put together a draft resolution (the

language possibly borrowed heavily from Locke's Two Treatises on

Government) and submitted it to the committee where it underwent

changes,1 and then it was presented to the full Congress at the end of

June. The famous Preamble states the case clearly:

We hold these truths to

be self evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed

by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are

Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these rights, Governments are

instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of

the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive

of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it,

and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such

principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall

seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

When the Congress moved to a preliminary vote on

the independence resolution on July 1st there was by no means unanimity

in the Congress. Several states voted no. But nine voted yes, so the

resolution was approved as ready for a final vote the next day, July

2nd. On that day a formal vote was taken, with Pennsylvania, South

Carolina, and Delaware finally lining up in support of independence.

New York, still having no instructions from its assembly in exile,

again abstained – but got instructions a week later to support

independence. The document was put in its final edition on the 4th of

July – and then (no one is sure exactly when) the delegates began

adding their signatures to the document.

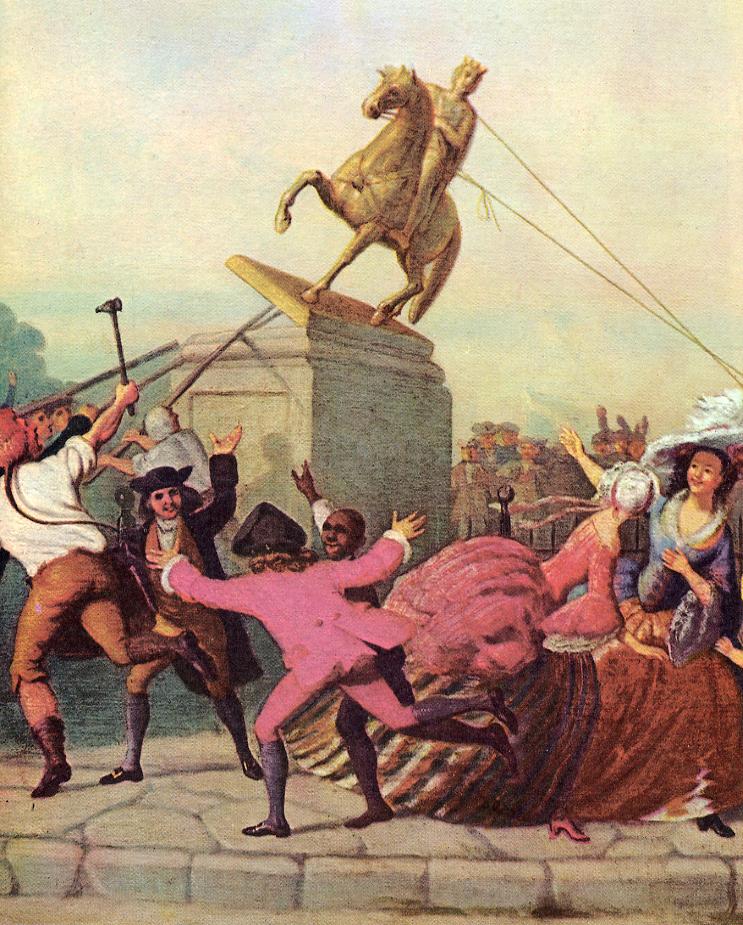

Now the colonies were no longer just that. As they saw things, they were now thirteen free and independent states.

1Words

and sentences were revised, and about 1/4th of Jefferson's text was cut

out – including an assertion by Jefferson that slavery had been forced

on the colonies by Britain – causing Jefferson to be deeply irritated

by this editorial slighting of his personal creativity! Also the irony

in Jefferson's statement that all men are created equal was the fact

that he himself owned a number of slaves, who, though men, were

certainly not created equal or endowed with certain unalienable Rights.

|

All-out battle at Breed's and Bunker

All-out battle at Breed's and Bunker The failed attempt to bring Canada

The failed attempt to bring Canada The British are forced to vacate

The British are forced to vacate The Declaration of Independence –

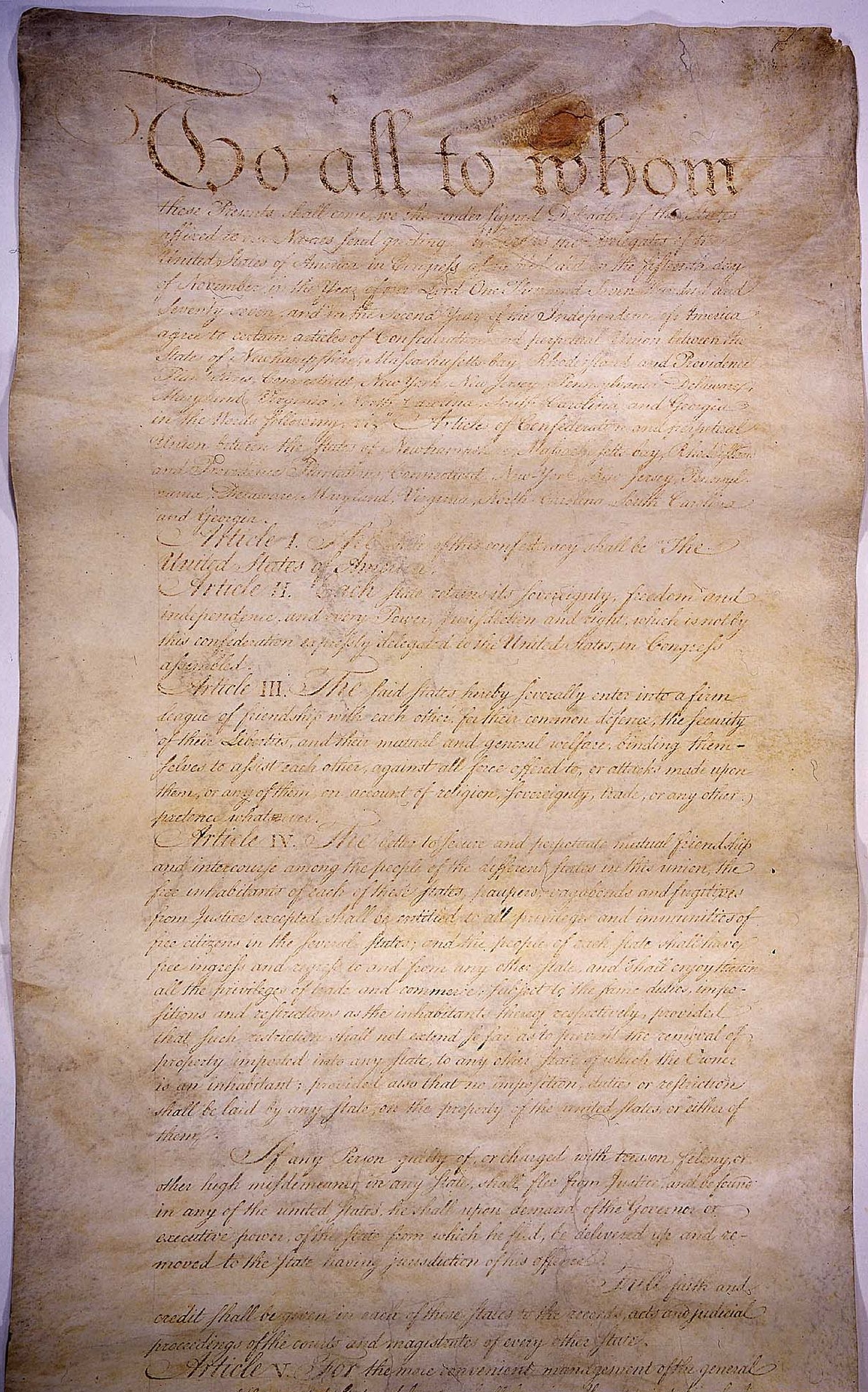

The Declaration of Independence – The Articles of Confederation –

The Articles of Confederation –