3. INDEPENDENCE

THE MILITARY CAMPAIGNS

1776 to 1781

CONTENTS

The matter of personal character The matter of personal character

Popular support for the war Popular support for the war

The military campaigns in the North (1775-1778) The military campaigns in the North (1775-1778)

The military campaign moves South (1778-1781) The military campaign moves South (1778-1781)

The action in the West The action in the West

The battle at sea The battle at sea

The textual material on this webpage is drawn directly from my work

America – The Covenant Nation © 2021, Volume One, pages 122-137.

|

|

A Timeline of Major Events during this period

| 1770s

|

The War initially does not go well for the Americans ... though Washington refuses to quit

1776 Washington's army escapes encirclement at Brooklyn Heights (Aug); but loses New York to the British

Washington defeats the Hessians at Trenton and Princeton (Dec) - reviving American spirits

1777 Washington is unable at Brandywine to stop Howe’s British advance on

Philadelphia (Sep) or dislodge them at Germantown (Oct)

However, Americans under Horatio Gates (with a lot of help from Arnold and Morgan) defeat a huge British army at Saratoga (Oct)

Washington’s

exhausted troops enter winter quarters at Valley Forge (Dec)

Gates

participates in the failed Conway Cabal to take command from Washington

(late 1777 early 1778)

1778 The Saratoga victory leads to the French Alliance (Feb)

Jones captures the British battleship HMS Drake (Apr)

The British now under Clinton

decide to vacate Philadelphia in order to better defend New York City

Because of the cowardice of

American Gen. Lee, Washington narrowly miss a potential defeat of Clinton’s British army at Monmouth (New Jersey) on its move to New York (Jun)

Clinton then decides to shift the war to the American South, where Tory

(pro-British) sentiments are stronger

The British take a lightly defended Savannah (Dec)

1779 Spain joins France as an American ally (Apr)

An American effort to retake Savannah fails (Oct)

|

| 1780s |

The battle in the American South intensifies

1780 Clinton captures a huge American army under Southern commander Gates at Camden (South Carolina) (May)

Charleston also falls to the British (May) – another huge American loss

Arnold switches

sides; his plan to turn West Point over to the British fails and he

narrowly escapes capture (Sep)

But Arnold – now serving the British – captures Richmond (Dec)

1781 Morgan defeats Tarleton’s Raiders at Cowpens – a major American victory (Jan);

America's new

Southern commander Nathanael Greene draws British Gen. Cornwallis into

Virginia

|

THE

MATTER OF PERSONAL CHARACTER |

|

Washington – the warrior

George Washington's appointment by the

Continental Congress as commander of the newly authorized Continental

Army proved to be a very Providential (as in Godly) choice. Whereas a

number of experienced Patriot officers (having also previously served

as officers in the British Army) coveted that position, Washington had

not. He accepted the responsibility only because he understood that he

was simply answering the call to duty – a call that came not just from

men but also from God. He was living out his destiny.

|

George Washington in uniform, as colonel of the First Virginia Regiment (1772)

by Charles Willson

Peale

Washington and Lee University

Collection

|

Washington, as sensitive as any of us to the

opinion of others, had taught himself at an early age to discipline his

feelings and move forward toward his calling regardless of the

obstacles (usually human) thrown before him. But he also knew that

there was a special hand on his life, a special place in the affairs of

Providence (the term for God frequently used at that time) that not

only protected him, but opened the way for him to move ahead in life.

He thus combined faith and personal discipline in a way that inspired

others. He sought honor by seeking first of all to be honorable. He was

highly demanding of integrity in himself – to be a man of honor.

As events were soon to demonstrate, he could be

rather forgiving of the lack of honor in his associates (such as his

colleagues Lee and Gates) who had given him little reason to expect

much from them anyway. But he could be quite demanding of integrity of

character and action when it came to those on whom he had come to

confer his trust (like Arnold).

Washington was unbending in his expectation of excellent behavior on

the part of the men under his command. But these expectations were

always accompanied by his equally strong sense of trust in these same

men. This conferral of his trust was a powerful instrument that

succeeded in getting the very best from others. The soldiers under his

command seemed always to try eagerly and sacrificially to live up to

that trust.

This was leadership, true leadership, and a real

blessing to a new nation trying to make its way forward into an unknown

future. Washington would not need to bark orders to those around him to

get them moving in the right direction. A simple word would be enough

to get things moving. People would be moved to right behavior sometimes

simply by his mere presence in their midst. This power of his almost

wordless presence (which happened daily as he moved among his soldiers

in the icy fields of Valley Forge) would prove in fact to be one of his

greatest contributions to the American cause, not only in war but also

in peace (such as his daily almost wordless contribution as chairman of

the Constitutional Convention gathered in Philadelphia the summer of

1787 to write the new American Constitution).

From where then did Washington draw such inner

strength of character if it clearly was not the approval of others? In

part it was almost something he seemed born with – a burning desire to

succeed. But the success he sought was both social as well as personal:

he was a man of incredible concern for the welfare of others. And he

seemed to have some well-cultivated instinct for doing things right –

right not only as social convention demanded, but at an even deeper

level, what he understood God or Providence required of him. Washington

was faithful in his time spent quietly in private prayer with God and

in his attendance in Sunday worship (although not necessarily regular

in this latter matter), fully convinced that there was no other way to

secure goodness and Truth for his world, personally and socially. His

sense of personal responsibility arose greatly from that powerful sense

of divine appointment. He lived and served, as he saw things, fully in

service to God and country – by God's will.

How that special relationship he had with God in

the midst of this crushing responsibility is well illustrated in the

Diary and Remembrances of a Presbyterian Minister Rev. Nathaniel

Randolph Snowden who recorded a conversation he had with Isaac Potts of

Valley Forge, Pennsylvania (at whose home Washington was residing that

winter):

I was riding with him (Mr. Potts) near Valley

Forge, where the army lay during the war of the Revolution. Mr. Potts

was a Senator in our state and a Whig. I told him I was agreeably

surprised to find him a friend to his country as the Quakers were

mostly Tories. He said, It was so and I was a rank Tory once, for I

never believed that America could proceed against Great Britain whose

fleets and armies covered the land and ocean. But something very

extraordinary converted me to the good faith.

What was that? I inquired. Do you see that

woods, and that plain? It was about a quarter of a mile from the place

we were riding. There, said he, laid the army of Washington. It was a

most distressing time of ye war, and all were for giving up the ship

but that one good man. In that woods, pointing to a close in view, I

heard a plaintive sound, as of a man at prayer. I tied my horse to a

sapling and went quietly into the woods and to my astonishment I saw

the great George Washington on his knees alone, with his sword on one

side and his cocked hat on the other. He was at Prayer to the God of

the Armies, beseeching to interpose with his Divine aid, as it was ye

Crisis and the cause of the country, of humanity, and of the world.

Such a prayer I never heard from the lips of

man. I left him alone praying. I went home and told my wife, I saw a

sight and heard today what I never saw or heard before, and just

related to her what I had seen and heard and observed. We never thought

a man could be a soldier and a Christian, but if there is one in the

world, it is Washington. We thought it was the cause of God, and

America could prevail.

Washington's understanding of the challenge before him

Indeed the appointment of Washington as the commander of the

Continental Army was a Providential choice1 also because he understood

the way that Americans would have to fight the huge English military

machine better than anyone else around him. He understood two things:

1) to engage the huge English army not directly, but indirectly, using

the element of surprise (Indian style) and 2) remember that wars are

not won in one great battle, but instead through the staying power of

one side willing to fight on longer than the enemy.

Battles bring the victor immediate glory. And a

great number of the men, especially other generals in the American

army, were eager to attain that glory. They were primarily focused on

the next battle, eager to get a chance to gain glory. Victory was not

only extremely thrilling in its moment of arrival (a kind of military

high), it gave the victors greatly enhanced status with others.

However, Washington well understood that while victory in battle may

bring glory, it does not necessarily win wars. And his sense of duty

always made very clear to him that he was called to win a war, not gain

impressive victories in battle.

This may seem puzzling to many even today. Aren't

the victories in battle what ultimately win wars? Maybe – and maybe

not. What actually wins wars is a breaking of the enemy's desire, for

whatever reason, to continue the conflict. Wars are won when one side

or the other is ready to call it quits.

Thus wars are fundamentally about morale, not

about military mechanics. Certainly a victory in a particular battle

improves the level of morale of one or the other side in a war. But it

generally takes more than one, or even several, military victories to

reshape morale to the extent that one side or the other is willing to

call it quits. Warriors usually have great staying power – and a loser

in battle can put this particular defeat behind him with the hope of a

possible win in the next round of the conflict. So in the end, a war is

won on the staying power of the contenders, not just the military

brilliance of one or another army and its commanders.

Washington's strategy

Thus while generals

in the various armies under Washington's command seemed out to win

battles – and the glory such battles earned them – Washington was

doggedly committed to winning the war, regardless of the fortunes of

battle. Washington knew that his primary function was to keep his army

of rebels (or Whigs or Patriots) intact and still troublesome to the

English (even if it was never fully victorious on the battlefield) –

until England tired of the game and was ready to call it quits and let

the Americans go freely on their way again.

Washington's inability to win the big one year

after year drew much criticism from others, especially other generals

who coveted the dignity of Washington's top position over the

Continental Army. Consequently, they frequently lobbied with the

Continental Congress behind Washington's back to have him replaced (by

themselves of course). But Washington seemed unruffled by these

endeavors of some of his associates. He was given a war to win. And by

the grace of God he was determined to fulfill his duty.

Ethical troubles behind Washington's back

So, character and understanding combined in Washington to produce

exactly the kind of leadership that the Patriots would need to get

through this war successfully. But other generals lacked that same

character. And from time to time America paid a big price for these

individuals' quest for praise and honor – at the cost of true wisdom

and eventually even their own success. In their quest for glory they

put themselves at the center of their devotion and lost sight of the

bigger agenda, the one which Washington was clearly following. They

became like gods in their own eyes, seeking all glory and honor for

themselves. Thus they failed to grasp the higher calling on America,

the one that God had placed before them, and the one that Washington

was attempting to answer. And God was with him. But as for the others,

God gave them over to the depravity of their own logic. And they at

some point self-destructed, sadly taking a lot of American morale or

spirit with them.

...their thinking

became futile and their foolish hearts were darkened. Although they

claimed to be wise, they became fools and exchanged the glory of the

immortal God for images made to look like mortal man ... (Romans 1:21-23 NIV)

General Charles Lee

General Lee was one of

those individuals. He had once been an officer in the British army and

considered himself more experienced and thus a better candidate than

Washington for the top position. As next in command under Washington he

had never been particularly supportive of Washington's military

efforts. Washington tolerated him and even accorded Lee proper

commanding privileges, though he was aware of Lee's maneuvering behind

his back. Also Lee was rather skillfully uncooperative as second in

command, more than once leaving Washington without his required

support, thereby putting Washington at an ever greater disadvantage in

facing the enemy.

At one point his purposeful dawdling with his

troops ironically gave the British the opportunity to capture Lee and

imprison him – until a prisoner exchange could be arranged. Washington

was not pleased to have him back. But he said and did nothing to

undercut Lee. Eventually it was a near catastrophe in a key battle

(Monmouth) caused by Lee's lack of the right kind of military instincts

that finally gave Washington the opportunity to rid himself of this

nuisance. However Lee fought back before the Continental Congress

because of his removal from command by Washington. But this thankfully

only worsened Lee's case before the members of the Congress, who were

beginning to catch on to Washington's real importance as the glue

keeping their army together.

1It

was also a wise human choice, because he was a Virginian and his

appointment made this more than just a New England rebellion, as it was

up to that point.

|

General Charles Lee – Gilbert

Stuart

New York, Metropolitan Museum

of Art

|

General Horatio Gates

General Gates, the

hero of Saratoga, was another one of those individuals. He too had been

a British officer and too believed himself to be the better candidate

for the top position. Washington's amazing success at Trenton at the

end of 1776 ended temporarily Gates's lobbying before Congress for

Washington's job. Gates was however eventually sent to take command of

the Northern Department. This put him directly in the position of

having to face the British at Saratoga in 1777. Saratoga was a success

and Gates the hero of the battle, though his fainthearted ways had not

been the cause of the victory. That honor truly belonged to others,

including Benedict Arnold, whose insubordinate attack on the British

had moved the morale considerably from the British to the American side

in this drawn-out battle. But in his self-promoting report on the

victory at Saratoga, Gates did not bother even to mention Arnold's

role.

Gates then soon joined a secret effort of a number

of top officers in the Continental Army to have their supporters in

Congress remove Washington from command (the Conway Cabal). This effort

fell apart when it was exposed publicly. Gates apologized to Washington

and survived politically. When two years later, as the Americans were

facing terrible losses in the Southern war, the hero of Saratoga was

given command of the Southern District. But the job proved greater than

his real abilities – and at Camden, South Carolina (1780), Gates' army

was crushed by the British. Gates was relieved of command, retired, but

then recalled from retirement (1782) to rejoin Washington – where he

may have been part of another plot (1783) to have Washington removed.

But by then the war was actually over.

|

Continental Army general

Horatio Gates – by Charles Willson Peale – 1782

Philadelphia, Independence

Hall

|

General Benedict Arnold

General

Arnold was another individual caught up in the maneuvering of Congress

in its politically inspired distribution of military commands and

military honors. But Arnold's situation was quite different from Lee

and Gates in that the maneuvering in Congress seemed, as with

Washington, to be aimed against Arnold, a man who was in fact one of

the most capable of America's generals. Arnold was constantly passed

over in Congress for promotions in favor of others, who often took

credit for Arnold's unheralded actions (such as Gates at Saratoga). At

one point, Congress even reprimanded Arnold for owing it money – though

he had exhausted most of his own personal fortunes on behalf of the

American war effort.

However, lacking Washington's moral and spiritual

self-discipline, Arnold gradually sunk into a deep bitterness and,

encouraged by his young pro-British or Tory Philadelphia bride, Peggy

Shippen, he decided to switch his services to the British side of the

war. He was planning, as the newly appointed commander (appointed by a

trusting Washington) of the key fortress at West Point, to turn the

strategic site on the Hudson River over to the British. But his plans

were discovered and the plot foiled (1780). However, he was able to

make his own escape down the Hudson to British lines. He was soon given

command of a British army unit and caused considerable destruction to

the American cause with his raids in Virginia and in his home state of

Connecticut.

After the war, living in England as an expatriate,

he was met by the English with rather mixed emotions. And he himself

began to have regrets about his betrayal. Sadly, his last request as he

approached death in 1801 was that he be buried not in his British but

rather in his American officer's uniform.

|

General Benedict Arnold

POPULAR SUPPORT FOR THE WAR |

Tories being forced from their

homes

|

The Americans themselves were greatly divided on the rebellion

Dark days lay ahead for the Americans. These dark days would also test

the character and spirit of all the colonials, civilians as well as

soldiers. By no means were all colonials supportive of this rebellion.

A large number of the colonials (estimates vary from 15 percent to 30

percent, with most of those concentrated in the southern colonies) were

opposed to the rebellion. As Tories or Loyalists, they stood with their

king on the issues. To be sure, an even larger number (estimates from

35 percent to 45 percent) of the colonials were active supporters of

the rebellion (strong in New England and the Middle Colonies). As Whigs

or Patriots, they filled the ranks of the militia – or as civilians

provided (supposedly) support in supplies or finances to the war

effort. And the rest, who were quite numerous themselves, were rather

neutral, tending to go with whichever side seemed at the moment to have

the upper hand.

Sadly some of the Whigs or Patriots supposedly

supporting the independence effort proved to be rather unreliable in

backing the Patriot soldiers in their attempt to defend that

independence. Many were quick to sell agricultural goods to the British

army in return for hard currency while their own armies starved.

Also, the states, loud in their support of the

idea of independence, were amazingly unwilling to come up with the

financial support necessary to pay even the minimum amount needed to

feed, arm and clothe the Patriot armies, a matter of huge frustration

to Washington, and to the other officers and soldiers sacrificing their

fortunes and lives in support of the independence effort.

The clergy and minority groups in the war

The clergy were themselves divided. The priests of the Church of

England assigned to parishes in America rather naturally supported the

Tory cause and simply retreated to England when the war broke out.

However, Congregationalist and Presbyterian pastors typically were

strongly supportive of the move to independence, their support at times

even active on the battlefield (often commanding militia units

themselves), so active that the Tories referred to them as the Black

Regiment (clergy wore black robes, though certainly not in battle!).

A favorite story about the involvement of the

clergy in the war arose from an event that occurred in 1780, when

Presbyterian pastor James Caldwell (whose wife had been killed by

Hessian troops when he was away) found the same Hessians soon returning

to his village of Springfield, New Jersey. When fighting broke out and

the Patriots ran out of paper wadding for their muskets, he ripped out

pages of his church's hymnbooks, Watts's Psalms and Hymns, and passed

them to the soldiers, shouting,"Put Watts into them, boys! Give them

Watts!"

On the political front, clergy took major

positions of leadership. One of these was John Witherspoon, a Scottish

Presbyterian pastor who came to the colonies in 1768 to take the

presidency of the College of New Jersey (the future Princeton

University). Under his presidency the college became a breeding-ground

for young leaders of the movement for independence, he himself then

becoming a delegate to the Continental Congress debating such

independence. Then as an official of the denomination, he called on

fellow Presbyterian ministers to speak out boldly on the matter of

American independence. And in 1776 he had the opportunity to sign the

Declaration of Independence, the only clergyman (and college president)

to do so.2

There were few Catholics in the colonies (mostly

concentrated in Maryland and southern Pennsylvania). Their position had

always been precarious, and the war at first did not change things. But

the alliance with Catholic France helped Catholics serve the Patriot

cause. But so did the leadership of the Carroll family, prominent

Catholics in Maryland. One of them, Father John Carroll,3 in fact a

Jesuit priest, early on was asked to represent the Patriot cause to the

French Canadians, in the hope of being able to ally with the Canadians

in the move to American independence. John's brother, Daniel, was a

signer of the Articles of Confederation and later the Constitution of

the United States, and a cousin Charles was a signer of the Declaration

of Independence and eventually a U.S. senator representing Maryland.

The Carrolls, like Jefferson, were understandably strong supporters of

the idea of separating religion from the affairs of civil government.

For a while, Protestant animosity towards Catholics would subside as a

result of the Carrolls' role in securing American independence and

subsequently its Republic.

For the German communities, mostly located along

the Pennsylvanian and North Carolinian western frontiers, the situation

was one that also required much caution. Lutherans were split, some

supporting the Patriot cause, others remaining Loyalists, because in

coming out of Germany they had found life in English America so much

more hospitable and felt that a spirit of gratitude towards English

authority for this better life was required of them. Then there were

the German Pietists, small groups of pacifists, such as the Protestant

Moravians (recently brought there from Germany by Count Nikolaus von

Zinzendorf) who found themselves torn as to which way to go in this

battle. They were, after all, pacifists.

Zinzendorf and the Moravians

The young

Saxon nobleman Zinzendorf in the 1720s had taken in Protestant Bohemian

and Moravian refugees escaping Catholic persecution in their homeland

(today's Czech Republic), a persecution that reached back to the days

of the Czech Reformer Jan Hus (burned at the stake by Church

authorities in 1415) when their religious reform movement (Unitas

Fratrum) got started. Zinzendorf created a retreat center for these

Moravians called Herrenhut. But sectarian controversies that developed

within Herrenhut and also with the German world around it compelled

Zinzendorf to focus his efforts in developing a true spirit of

Christian unity, resulting in an amazing Moravian pacifism – and an

equally amazing commitment to Christian mission work (the 1730s) under

the most difficult of conditions, especially among the African slaves

of the Caribbean (but also elsewhere).

It was their missionary work that first brought

them to Georgia in 1735, to be part of the philanthropic project that

Georgia was announced to be. They did not succeed greatly in that

endeavor – except to influence profoundly a young John Wesley, who took

up many of the Moravian approaches to ministry in his own subsequent

work in England. In 1741, the Moravians moved on to Pennsylvania,

finally establishing a successful mission station there at Bethlehem

and then soon at nearby Nazareth. From there they sent missions to many

other parts of the English colonies, most notably Salem (now

Winston-Salem) in North Carolina.

Now in the 1770s their pacifism made things

difficult for themselves as their newly adopted country chose sides in

this growing conflict between the colonies and their English king. The

Moravians attempted to stay neutral, but over time, and quite

gradually, found themselves supporting the Patriot cause.

2After the war, he would be the one to call together and lead the first national Presbyterian General Assembly.

3Father

John Carroll would become the first Catholic bishop in the United

States and also found Georgetown College in 1789 along the Potomac River.

THE MILITARY CAMPAIGN IN THE NORTH |

Keesee and Sidwell,

p. 118

Keesee and Sidwell,

p. 118

| Meanwhile

Washington, who had taken command of the Continental Army at Boston,

realized that the British pullout from Boston meant trouble further

south along the New England coast. He decided to pull his army

out of

Boston and reposition it in New York, on Long Island just opposite

Manhattan. But the British army arrived by ship in huge numbers

and

maneuvered Washington's army back into an encirclement along the

Brooklyn Heights (August, 1776). Washington and his men were

trapped.

The only thing Washington could do was to try to slip undetected by

night across the East River into Manhattan in order to escape this

trap. However, there was virtually no hope of being able to

rescue more

than a small portion of his army before the British would awaken to the

program and shut him down. But he had no alternative. And then

came a

mysterious fog which covered the East River and hid his escape –

lasting miraculously until mid-morning, allowing Washington to get

nearly his whole army away to safety. Clearly this was understood

by all Americans as an incredible intervention on God's part.

But of course wars are not won merely by escaping the enemy. But for

Washington, this seemed to be his only recourse – again and again. He

got his army out of another potential trap in Manhattan – but lost two

strategic American forts and over 3,000 troops taken prisoner by the

British in the process. New York City would remain in British hands

until the end of the war.

Depression

Washington then retreated through New Jersey and crossed

into Pennsylvania, the onset of winter and the tradition by which

armies rested in the winter rather than fight – giving Washington some

reprieve from continuing British pressure. Morale was low. People were

deserting nearby Philadelphia, fearing a British attack on the city.

Washington's Continental Army was down to about 5,000 soldiers, and

that number was dwindling fast. Worse, a good number of them had their

terms of enlistment running out at the end of December. At the same

time, facing the Americans was – or was soon to be – a growing British

Army of over 30,000 troops. Things were looking tragically grim for

Washington.

These are the times that try men's souls.

Thomas Paine – participant in the retreat of the Continental Army

Trenton (December 25-26, 1776)

To break the mood of depression,

Washington decided to conduct a surprise attack on the Hessian troops

serving the British at Trenton on the night of Christmas, when the

Hessians hopefully would be sleeping off heavy Christmas celebrations.

It was a daring maneuver: an ice-filled Delaware River to cross and

then a nine-mile march south to Trenton in the dead of a dark,

freezing, rainy-snowy night. But Washington seemed unshaken by the high

risk of it all. His confidence, which came from a serene higher sense

of things, inspired a similar confidence in his men. The attack, and a

secondary assault ordered by Washington on another British unit posted

nearby, succeeded brilliantly, with little loss of American life (two

killed) and yet 1,000 Hessians killed or captured (though a number of

American soldiers died in the following days from disease and

exhaustion caused by the wintery effort).

Princeton (January 3, 1777)

His amazing victory (many said miraculous

victory) was soon followed up by another – also stunning – victory

against a British unit sent to retake Trenton. Washington abandoned

Trenton, but defeated this English relieving force at nearby Princeton.

At first the battle looked as if it were going to be another disaster

for the Americans. But Washington managed to rally his troops and turn

a retreat into an attack – routing instead the British. It was another humiliating defeat for

the British.

These two victories of Trenton and Princeton were strategically small

militarily, but morale-wise they were huge boosts to the American

effort. Few soldiers abandoned Washington at this critical juncture.

Indeed, many men now signed up to serve under Washington. The

Continental Army remained a viable fighting machine.

|

Washington Crossing the

Delaware

prior to the American attack on Trenton the night of December 25, 1776 – by Emanuel Leutze

New York, Metropolitan Museum

of Art

The Battle of Princeton – January 3, 1777

Historical Society of

Pennsylvania

The two small victories at Trenton and then Princeton proved to be major moral boosters for his dwindling army ... keeping it from disintegrating

British Commander in New

York, Sir Henry Clinton ca. 1777

American battle dress (hunting

outfits) during the early years of the war (sketches by a Bavarian

officer serving in the British army)

collection of Mrs. John

Nicholas Brown

collection of Mrs. John Nicholas

Brown

collection of Mrs. John Nicholas

Brown

|

The Battle of Saratoga (September-October 1777)

The British had a plan to knock the Northern

colonies out of the war by breaking the vital line of communications

between New England and the Middle Colonies at New York, along the

upper Hudson River. They planned to bring a large part of their army

occupying New York City up the Hudson River to meet two other British

armies coming South from Canada.

But things immediately began to go wrong for the British. Colonial

militia used every trick in the book to slow up the movement of the

British groups descending from Canada. And a section of the British

army was overrun (1,000 men killed, wounded or captured) at Bennington

in August. Another British group returned to Canada when their Indian

allies abandoned them upon hearing that Arnold was commanding the

colonials opposing them.

Meanwhile the British commander in New York City, William Howe, sent

his men not up the Hudson but off on an expedition to capture

Philadelphia. Finally in September the remnants of the British army

(6,000 soldiers under General John Burgoyne) met the Americans (8,000

soldiers under General Gates) at Saratoga, New York. The results of a

hard-fought encounter were at first inconclusive and the situation

settled into a stalemate. Burgoyne kept waiting for British

reinforcements – which never came. Meanwhile in the American ranks,

which were actually growing at this time, friction had grown between

Gates and his subordinate commander (but militarily aggressive) Arnold,

and a jealous Gates sidelined Arnold, forcing him into a largely

inactive role.

When battle resumed in October the British were forced slowly to give

ground. Then Arnold disobeyed Gates and led a charge on the weakening

British line – firing up the American lines which in turn delivered yet

another crippling blow to the British. Surrounded and exhausted, now

certain that he would receive no aid from Howe, Burgoyne finally

surrendered his entire British army to Gates. Gates thus became the

"hero of Saratoga," an irritated Gates endeavoring to make sure that

Arnold's role in the victory would go unnoticed by Congress.

The French join the war on the American side (February 1778)

With

this stunning defeat of a large British army by a clearly effective

American army, the French King Louis XVI lost all hesitation and openly

declared himself an ally of the Americans (the French, along with the

Spanish and Dutch, had previously been quietly slipping support to the

American rebels). British General Howe had indeed taken the American

capital of Philadelphia in September (1777). But that achievement

seemed less significant to the French than the American capture of

6,000 British soldiers in October. Thus in February (1778) America and

France became wartime allies.

The loss of Philadelphia (1777)

For Washington, things had not gone

well. He was not part of the glory of Saratoga. Instead he had been

trying to follow and anticipate Howe's moves in removing his troops

from New York. Howe's intent finally became clear in August when Howe

moved by water up the Chesapeake in the direction of Philadelphia.

Washington tried to block the advance of the larger army, but was

outflanked at Brandywine (September) and thus forced to allow Howe to

enter Philadelphia virtually unopposed. Then a stalemate set in as

Washington tried unsuccessfully to capture the Germantown garrison just

north of Philadelphia (October). And then the British tried, equally

unsuccessfully, to take Washington at White Marsh (December).

|

Benedict Arnold leading American

troops against British regulars and Indians at Freeman's Farm south of Saratoga – October

7, 1777

Fort Ticonderoga

Museum

British General Burgoyne

surrenders to American General Gates at Saratoga – by John Trumbull

(1820)

United States Architect

of the Capitol

|

Wintering at Valley Forge (1777-1778)

At this point it was time for the armies

to move into winter quarters. It would be another very trying time for

Washington's Continental Army. Of the 10,000 troops that went into

winter quarters at Valley Forge just outside Philadelphia, 2,500 of

them would die there of cold, hunger and disease before the next spring

arrived. But it would be a very different army that would finally

emerge from the experience. Mere survival that winter, not to mention

success in the next year's military campaign, would require discipline.

And the troops got just that from the experience. Military training

from Prussian Baron von Steuben and spiritual discipline from the pious

rigor Washington maintained in his own life and the same discipline he

expected of his men (including daily prayers) brought a quite

disciplined army back into service in the late spring of 1778.

|

The Battle of Germantown – October 24, 1777

The Battle of Germantown – October 24, 1777

Valley

Forge Historical

Society

Washington and Von Steuben

at Valley Forge, Winter of 1777-1778

Washington at prayer during those tough Valley Forge days – Arnold Friberg

Washington at prayer during those tough Valley Forge days – Arnold Friberg

|

Monmouth (June 28, 1778)

With the French in the war, the British decided to

abandon Philadelphia and return their troops to New York, fearing a

French naval assault on that city. Howe resigned and General Henry

Clinton took over as commander of the British armies in America. All

the way from Philadelphia back to New York City, Washington shadowed

Clinton's march.

Finally, as the British troops passed the Monmouth

Court House,

Washington saw an opportunity and ordered a surprise attack on the rear

of Clinton's army. The arrogant and temperamental General Lee

originally had refused the honor of commanding a small military unit

ordered by Washington to lead the attack – but changed his mind when he

saw how glad Washington was that he had said no, and subsequently

requested command of the forward attack force. But Lee lost heart in

the midst of the battle when British General Charles Cornwallis

counterattacked. Without consulting Washington, Lee ordered a retreat –

which turned into a rout. Washington came upon the fleeing Americans,

took direct command, and quickly reorganized his men for a

counterattack. The battle raged back and forth until nightfall, when

both sides were forced to break off the fight. That night Clinton

slipped his men away to continue their march to New York City.

For Washington this was not the victory he had hoped for, though it

finally allowed him to get rid of the troublesome General Lee, who was

disgraced by his actions. But it did prove that under proper command

his disciplined troops were fully capable of taking on directly an

equally manned and equipped British army.

This would also be the last major battle in the American North

(although smaller battles would continue in the Middle Colonies).

|

Washington rallying his troops at the Battle of Monmouth

(after Lee had ordered a retreat ... which turned into a rout)

June 28, 1778

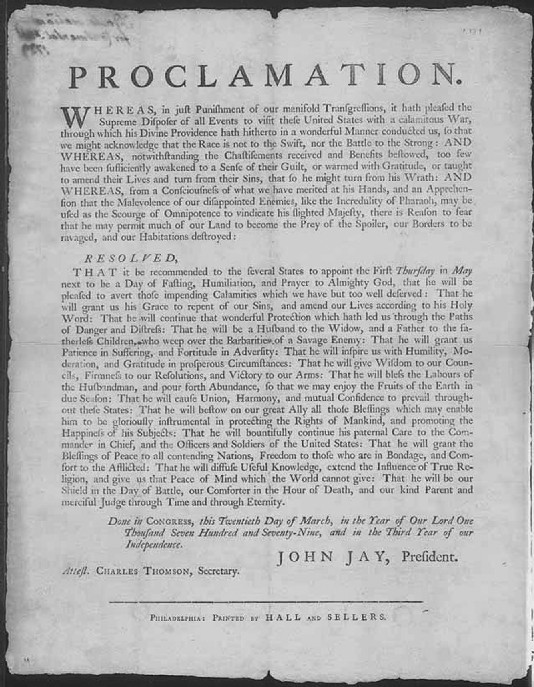

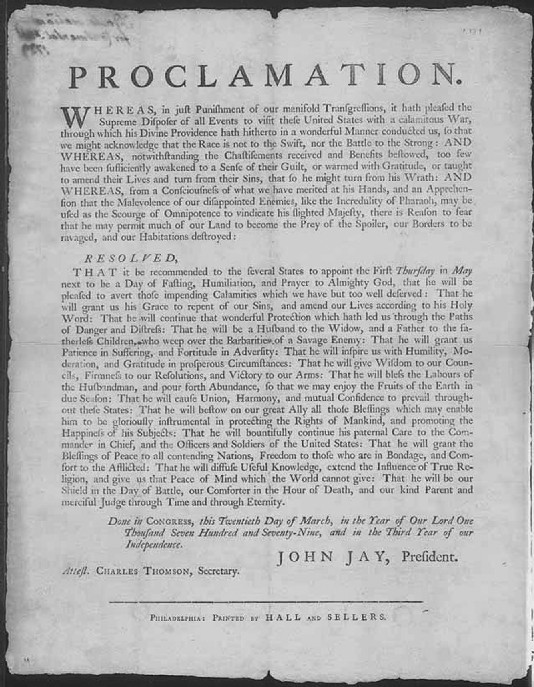

The Continental Congress in March of 1779 calls on the States to appoint the first Thursday in May as a Day of Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer to Almighty God.

THE

MILITARY CAMPAIGN MOVES SOUTH |

Keesee and Sidwell,

p. 124

Keesee and Sidwell,

p. 124

| Failing

to get any traction in the North, the British decided to move their

activities to the South, where it was hoped that a large number of

pro-British American Tories might help deliver that part of colonial

America over to the British forces. The British were assured that with

the show of a few British victories in the South, the Tories would come

out in huge numbers in support of the British effort. But making that

happen proved to be more difficult than the British at first had hoped.

Early British and Tory (or Loyalist) failures in the South (1776-1778)

From the very beginning of the war things went terribly wrong for the

British and their Tory Loyalists in the South. The British governors in

the South had been trying to form Tory militia since the outbreak of

the conflict in early 1775. Plans were also to bring Redcoats to the

Carolinas to join up with Southern Tories. But Whig or Patriot militia

were also forming rapidly in the South. Hearing of British plans to

land a force of Redcoats in the Carolinas, both sides, Whigs and

Tories, began to mobilize in anticipation of this event.

Both sides met at Moore's Creek Bridge (North

Carolina) in February of 1776 – and the Tories were soundly defeated by

the Patriots. Though the conflict was small in scale (less than 1,000

on each side) the result of the conflict was the tremendous quieting of

Tory sympathies in the South.

The British now had to depend largely on their own

forces. Unable to find a secure landing in North Carolina for the

soldiers and supplies necessary to support their effort to crush the

Southern rebellion, they turned toward the major southern seaport of

Charleston. But they mistakenly landed their soldiers on Sullivan

Island, and thus tried to subdue the defending American fort by ship's

canon rather than troop assault across deep waters. But the palmetto

logs forming the American outer defenses easily took the shelling – and

the fort proved impregnable. Thus the British simply called off the

attack on Charleston – and pretty much the entire southern effort.

British Florida, protected by the British fort at

St. Augustine, remained in British hands – and became a place of refuge

for Tories fleeing the reprisals of the Southern Patriots. But the

British seemed unable to acquire any advantage from this strategic

position (partly due to political squabbles within the British upper

political circles). Eventually British Florida would be able to

contribute to the war, but not with the impact that it originally would

have had on the war if it had been able to get going earlier.

With the failure of the British to gain what

should have been a much easier victory in the South, they lost the

valuable strategic advantage they had – and probably the war itself. If

they had taken the South out of the war in its early days it would have

undoubtedly collapsed the entire colonial rebellion. But they let that

opportunity slip from their hands. Indeed, for the next two years the

Tory or Loyalist position in the South only worsened as British support

failed to appear and as Patriots did their best to drive the Loyalists

out of the area.

The British now focus their war effort on the South (1778)

Then after the Battle of Monmouth, with the growing awareness of the

British that they would not be able to make much further progress in

the North, British attention turned decidedly to the South. Once again,

the hope was to seize a southern seaport in order to offload soldiers

and supplies for a major southern offensive.

Savannah

The target this time was Savannah. It was defended only by some 700

Patriots and thus easily taken in December by a British force of 3,500

troops arriving by sea, even before 2,000 British troops coming up from

Florida had a chance to assist in the action. The British now had

a seaport available to begin bringing in soldiers and supplies to knock

the South out of the war. Savannah would continue to serve the British

well in that capacity. A French and Patriot effort to retake the

city the following year (October 1779) failed miserably, resulting in

the loss of about 1,000 French and Patriots killed, wounded or

captured.

Charleston

Things then seemed to go from bad to much worse for the Patriots when

British General Clinton directed a joint land and sea offensive of

around 14,000 troops and ninety ships against the city of Charleston,

defended by a force only about a third that size. British General

Charles Cornwallis, who was commanding the land force, was soon able to

cut off the land routes in and out of the city and then begin the

assault on the city itself. As the weeks went by it became apparent to

the American commander Lincoln that the city could not hold out and a

decision was made simply to surrender the city and the 5,000 American

troops protecting it. It was the worst American military defeat of the

war – and sent a shock wave through the colonies.

The Siege of Charleston (May 1780)

General Charles Cornwallis

British Commander in the

Southern Campaign

Col. William Moultrie

American

commander of the fort at Sullivan's Island outside of Charleston

National Park Service

Americans holding off the

attack of 10 British ships at Sullivan's Island – 1776

The Capitol

Charleston surrounded by British navy and 14,000 British ground troops

and finally forced to surrender its 5,000 troops

... America's worst defeat in the war (March 29-May 12, 1780)

|

Camden

If things were not bad enough, they got even worse

for the Patriots

when Gates, the supposed genius of Saratoga, was sent to take over the

Southern Department. Believing himself to be something of a brilliant

military leader, he decided on the strategy of a direct assault against

Cornwallis's well-seasoned army. Gates was commanding a larger army –

but poorly organized and mostly inexperienced. In August (1780), at

Camden, South Carolina, the two sides met. The results for the Patriots

were terrible. Gates's militia troops broke ranks and fled, leaving now

only 800 Continentals to face 2,000 British troops. Colonel Banastre

Tarleton's cavalry charge quickly scattered even these Patriot troops.

The battle was quickly over. The losses for the Americans were enormous

(the loss of over 2,000 men), not only numerically but also

morale-wise.

|

American General Gates' troops are routed at the Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780) and

loses 2,000 troops (half of them captured) and an enormous amount of

military supplies ... compared to a relatively light loss of British

troops, most of them American Tories. American morale is now running very low.

British Cavalryman Banastre ["Bloody"] Tarleton ... also known as "the Butcher" – by Sir Joshua Reynolds

London, National

Gallery

|

Waxhaws

The war in the South now turned into a very nasty guerrilla-style

action as British troops under Tarleton had earlier moved into the

rural interior seeking to break the last of the Patriot resistance with

a harsh strategy of burning out Patriot farms and towns as they went.

At the battle of Waxhaws, South Carolina (May 1780) the troops of

"Bloody Tarleton" had even cut down several hundred Patriot soldiers

after they had surrendered. But Patriot partisans (led by such men as

Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox") fought back all the more relentlessly.

And Tarleton's tactics ultimately succeeded only in driving many

American neutrals into the ranks of vengeful Patriots.

King's Mountain

In October (1780) at King's Mountain, North Carolina, a Patriot army of

around 900 surrounded and destroyed a Tory or Loyalist army of about

1,400 – also crushing once again Southern Loyalists' enthusiasm for

open military support of the British regulars. The war in the South now

began to turn in favor of the Patriots.

Cowpens

Then things also turned quite badly for the British regulars. Tarleton

had been sent out by Cornwallis to chase down Patriots under the

command of Nathanael Greene (who had taken over the Southern Department

from Gates). At Cowpens (January 1781), along the flooded Broad River,

Tarleton, after a hard forced march of his men in pursuit of retreating

American forces, met an American unit under one of Greene's most able

commanders, Daniel Morgan. But Morgan had set up a skillful trap for

Tarleton – and the brash Tarleton sent his men straight into it.

Tarleton's men were soon surrounded – and annihilated. Tarleton and a

handful of his cavalry were able to escape. But the rest of Tarleton's

force was destroyed, including some of Cornwallis's best regiments.

Guildford Court House

Cornwallis was now desperate for a win to undo the catastrophes he had

experienced at King's Mountain and Cowpens. He headed north after

Greene's army, to try to wipe it out in a decisive blow that might

swing the advantage back to the British. Greene and Cornwallis met at

Guilford Court House, North Carolina, in May – and Cornwallis's army of

only 2,000 men indeed succeeded in defeating Greene's army, which was

twice the size of his. Greene was forced to retreat and leave the field

of battle to Cornwallis. But Greene was also able to give Cornwallis

the slip. And though Greene had lost the battle, his army was still

quite intact. However, Cornwallis's victory had come at a huge cost in

British casualties that he could not afford. Nonetheless Cornwallis

persisted in his effort to try to chase down Greene and his Continental

Army, only to have Greene constantly give him the slip. The effect on

Cornwallis's troops was exhausting.

|

Nathanael Greene (1783) – by Charles Willson Peale

He was given the Southern command after Gates' failure at Camden

London, National

Gallery

The Battle of King's Mountain (October 7, 1780), in which Patriot troops destroyed an army of Loyalist troops, collapsing Loyalist support for the British ...

an important turning point in the war in the South

The Battle of King's Mountain (October 7, 1780), in which Patriot troops destroyed an army of Loyalist troops, collapsing Loyalist support for the British ...

an important turning point in the war in the South

The Battle of Cowpens (January 17,1781)

American General Daniel Morgan destroyed Tarleton's forces when he lured them into a trap ... building further American Patriot fighting morale

General Daniel Morgan

The "Swamp Fox" Francis Marion

harasses British troops while avoiding direct confrontation. Here he is treating a British officer to a meal of potatoes (by John Blake White)

The "Swamp Fox" Francis Marion

harasses British troops while avoiding direct confrontation. Here he is treating a British officer to a meal of potatoes (by John Blake White)

Old Print Shop

The Battle of Guilford Court House (March 17, 1781)

Cornwallis's troops managed to defeat an American force under Greene twice his size. It looked like a huge British victory. But Greene escaped with his army still intact. And it cost Cornwallis heavily in terms of troops and supplies that he could ill-afford to lose.

And he would exhaust himself further trying (unsuccessfully) to run down

Greene and his army.

Keesee and Sidwell,

p. 123

George Rogers Clark – by

James Barton Longacre

National Portrait Gallery – Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Sea captain John-Paul

Jones

Independence National Historical

Park, Philadelphia

John-Paul Jones' Bonhomme

Richard defeats the British frigate Serapis – 1779

U.S. Naval Academy

Museum

Miles H. Hodges Miles H. Hodges

| | | |

The matter of personal character

The matter of personal character Popular support for the war

Popular support for the war The military campaigns in the North (1775-1778)

The military campaigns in the North (1775-1778) The military campaign moves South (1778-1781)

The military campaign moves South (1778-1781) The action in the West

The action in the West The battle at sea

The battle at sea